hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] Breaking down Biden’s approach to relations with S. Korea, China and Japan

Joe Biden’s election as the next president of the US raises questions regarding the foreign policy he’ll adopt in East Asia, at the complex and much-vexed junction of South Korea, China, and Japan.

As part of the US’ struggle with China over future hegemony, the US is expected to keep pushing for improved relations between South Korea and Japan, two key American allies in the Indo-Pacific. The relationship between the two has been allowed to reach a point of unprecedented deterioration.

Biden could also ask South Korea to demonstrate more allegiance to the alliance and advise South Koreans not to bet against the US. In this article, we’ll look at three decisive scenes that can inform speculation about what the Biden administration’s East Asia policy will look like.

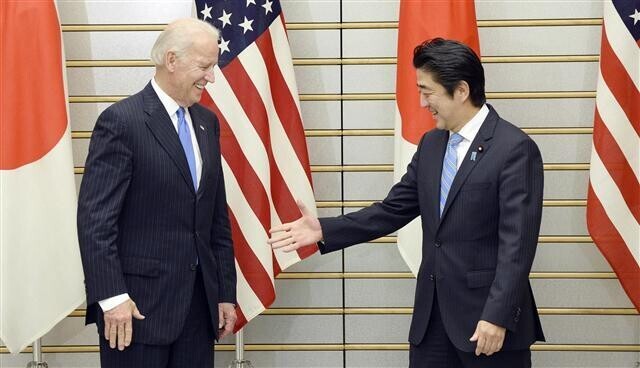

Rewind the tape seven years to Dec. 12, 2013. That’s when Joe Biden, as vice president under President Barack Obama, urged Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe not to pay his respects at the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, where known war criminals are enshrined. Abe retorted that he would decide for himself whether or not to go.

Biden and Abe’s argument took place during an hour-long phone call that began at 10:40 pm. Biden was trying to stop Abe — a historical revisionist who basically denies Japan’s past acts of aggression — from visiting Yasukuni Shrine, which honors the “Class A” war criminals who initiated hostilities in the Pacific War.

While the Trump administration has taken little interest in assuaging South Korea and Japan’s bitter dispute over outstanding historical issues, the Obama administration tried to act as a mediator to maintain a healthy cooperative relationship between two crucial allies. In 2013, just as today, Seoul and Tokyo’s relationship was repeatedly disrupted by the question of how to resolve the comfort women issue, referring to women from Korea and other countries forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese imperial army.

Today, Japan refuses to attend a trilateral summit with China and South Korea until South Korea takes “acceptable action” on the issue of compensation for victims of forced labor during Japan’s imperial rule over Korea. But back in 2013, it was South Korea that had backed out of a summit with Japan, demanding that Japan take “sincere action” to resolve the comfort women issue. The issue was creating a serious headache for the US.

On Dec. 6, just a few days before the phone call took place, Biden had met with then South Korean President Park Geun-hye while on a tour of South Korea, China, and Japan, and asked her to work on improving South Korea-Japan relations. Biden was in a position to make that request because he’d confirmed Japan’s forward-looking position on its historical dispute with South Korea in a meeting with Abe on Dec. 3, just three days earlier.

The Asahi Shimbun and other Japanese newspapers reported at the time that Abe had acknowledged to Biden that Japan had been excessive in its relationship with South Korea and had promised to uphold the Murayama Statement and the Kono Statement and to not pay his respects at the Yasukuni Shrine. Armed with those encouraging remarks, Biden put pressure on Park, arguing that it was time for South Korea to make some concessions of its own.

In that context, Abe paying a sudden visit to Yasukuni was sure to make Biden look like a liar who’d led Park on.

But in the phone call with Biden, Abe only said he’d make his own decision about the shrine visit, without promising to call it off. Just as Biden had feared, the Japanese prime minister went ahead with his visit on Dec. 26 of that year.

Half an hour after Abe’s visit, the US Embassy in Japan took the unusual step of releasing an angry statement. “The United States is disappointed that Japan’s leadership has taken an action that will exacerbate tensions with Japan's neighbors,” the statement said.

One more interesting anecdote can be described here. Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, while he was still the chief cabinet secretary, had consistently opposed Abe’s visit to Yasukuni. Unable to change Abe’s mind, Suga made a conciliatory phone call to Lee Byeong-gi, South Korea’s ambassador to Japan, half an hour before the visit took place.

Given his poor command of Japanese, Lee wasn’t sure of how to respond to the news of Abe’s impending visit to the shrine. His course of action was suggested by Kim Won-jin, the counselor for political affairs who was standing beside him. “Ambassador, you should say, ‘Tsuyoku kougishimasu,’” Kim said, using a Japanese phrase meaning “We strongly protest.”

Suga was on such good terms with Lee during his tenure as ambassador that the two made a point of eating together once a month. That relationship of trust provided the impetus behind the agreement that the two countries reached on Dec. 28, 2015, hoping to resolve the comfort women issue. Later, though, that agreement would become an albatross around Lee’s neck.

Our second scene occurred in April 2015, when Biden praised Abe’s speech before Congress as being “very tactful and meaningful.”

While it’s true that Biden has a deep understanding of South Korea and Japan’s historical disputes and the comfort women issue, among and other issues of human rights, it’s not clear that he’ll take South Korea’s side on the two countries’ current dispute about compensation for victims of forced labor. In the end, the most important thing for Biden isn’t whether South Korea or Japan is right but the US’ national interest.

While the US had voiced strong disappointment about Abe’s visit to Yasukuni in December 2013, by 2015, it had reached the strategic conclusion that it needed to reinforce its alliance with Japan to counter the growing power of China. In the end, Biden endorsed the ambiguous historical attitude that Abe offered without clearly apologizing to Japan’s neighbors.

The most dramatic illustration of this came with Abe’s speech before a joint meeting of the US Senate and House of Representatives on Apr. 29, 2015. During that address, Abe made reference to the losses Japan had caused for the US in the past with events such as the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the Bataan Death March, an incident of abuse against US prisoners captured in the Philippines. “History is harsh. What is done cannot be undone,” he said. “With deep repentance in my heart, I stood there in silent prayers for some time.”

But in contrast with the 1995 Murayama Statement, which clearly stated a message of apology and remorse for Japan’s imperial invasions, Abe’s address did not use any language that could be construed as an apology. Instead, the message he shared was a self-congratulatory one.

“Later on, from the 1980’s, we saw the rise of the Republic of Korea, Taiwan, the ASEAN countries, and before long, China as well. This time, Japan too devotedly poured in capital and technologies to support their growth,” he declared at the time. While it triggered expressions of discontent from both South Korea and China, Biden called Abe’s address skillful and significant, adding that he “thought he made it very clear that there was responsibility [for historical events] on Japan’s part.”

In fact, US pressure on Japan to quickly resolve its historical friction with South Korea dates back to early 2015. In a speech delivered at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace on Feb. 27, 2015, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Wendy Sherman -- then the third-in-command at the US State Department, said that “nationalist feelings can still be exploited, and it’s not hard for a political leader anywhere to earn cheap applause by vilifying a former enemy.”

In an interview with the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper the following Apr. 8, then Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter stressed the American position that “the potential gains of [South Korea-Japan] cooperation [. . .] outweigh yesterday's tension and today's politics” and that “our three nations must look toward the future.”

Under this pressure from Washington, the Park Geun-hye administration had no choice but to agree to the comfort women agreement of Dec. 28, 2015. With its General Security of Military Information Agreement (GOSMIA) with Japan in November 2016 and the deployment of a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system in early 2017, South Korea took additional decisive steps toward establishing a three-way alliance with the US and Japan.

Firm stance on China

“It's never been a good bet to bet against America.” (to South Korean President Park Geun-hye during a December 2013 visit to South Korea)

“I have spent many hours with [China’s] leaders, and I understand what we are up against.” (in a contribution published in the March/April 2020 issue of the US journal “Foreign Affairs”)

Biden is considered one of the US’ foremost diplomatic experts, having spent 12 years chairing the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and eight years as the vice president. As such, he has a deep understanding of the US-China conflict that represents the single biggest task in US foreign relations, and he has shared his own “solution” in various forums.

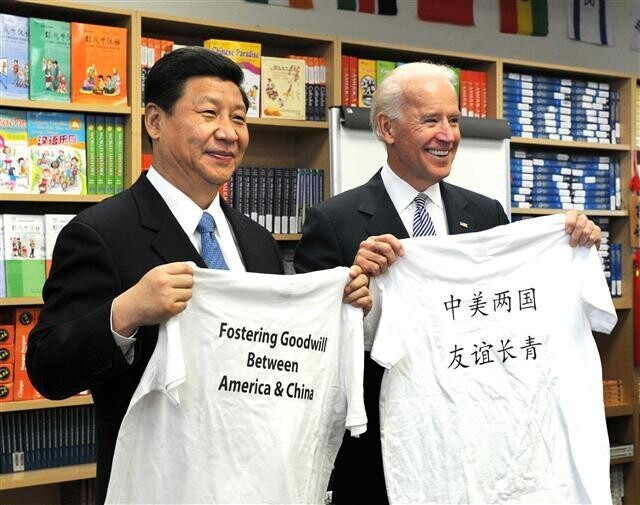

In a contribution published in the March/April 2020 issue of “Foreign Affairs,” Biden wrote that he has “spent many hours with [China’s] leaders.” Indeed, he and Chinese President Xi Jinping are “old friends,” a relationship dating back to the early 2010s. Biden first met Xi while serving as the vice president under the Barack Obama administration, when Xi, then the Chinese vice president, was receiving training as top leader under President Hu Jintao. Biden and Xi would go on to establish a friendship with mutual invitations extended in 2011 and 2012. The two watched an LA Lakers game together during Xi’s US visit in February 2012; in December 2013, they held difficult talks in Beijing -- with Xi now as Chinese president -- over the issue of China’s unilateral expansion of its Air Defense Identification Zone in the East China Sea.

Biden appears likely to carry on the broader framework of the Trump administration’s Indo-Pacific policies toward China and Asia in general. If there is a difference from the Trump administration, it is the greater importance accorded to cooperation with allies rather than an “America first” attitude. Commenting on US policies toward China in his “Foreign Affairs” piece, Biden wrote, “To win the competition for the future against China or anyone else, the United States must sharpen its innovative edge and unite the economic might of democracies around the world to counter abusive economic practices and reduce inequality.”

This approach would be reaffirmed four months later when the Democratic Party’s policy platform was unveiled in August. The “Asia-Pacific” category of that platform stated, “As a Pacific power, the United States should work closely with its allies and partners to advance our shared prosperity, security, and values—and shape the unfolding Pacific Century.” It also stressed, “Democrats' approach to China will be guided by America's national interests and the interests of our allies, and draw on the sources of American strength -- the openness of our society, the dynamism of our economy, and the power of our alliances to shape and enforce international norms that reflect our values.”

In his piece, Biden repeatedly emphasized expressions such as “democratic” -- in reference to countries around the world -- and “allies and partners.” Biden’s mindset in terms of achieving US interests was reaffirmed in an Oct. 30 contribution to Yonhap News. “As President, I'll stand with South Korea, strengthening our alliance to safeguard peace in East Asia and beyond, rather than extorting Seoul with reckless threats to remove our troops,” he declared, adding that he would “engage in principled diplomacy and keep pressing toward a denuclearized North Korea and a unified Korean Peninsula.”

Ultimately, Biden appears likely to demand closer, multilayered cooperation from South Korea, while using much more sophisticated and skilled diplomacy than the Trump administration to achieve the US’ strategic goal of triumphing in the power battle with China. In the process, he is very likely to demand a clearer position from Seoul between the US and China, or to make potentially awkward requests to quickly improve relations with Japan. Indeed, in a conversation with then President Park Geun-hye on Dec. 6, 2013, Biden stressed, “It's never been a good bet to bet against America [. . .] and America will continue to place its bet on South Korea.”

By Gil Yun-hyung, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 4After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 7US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 10[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda