hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

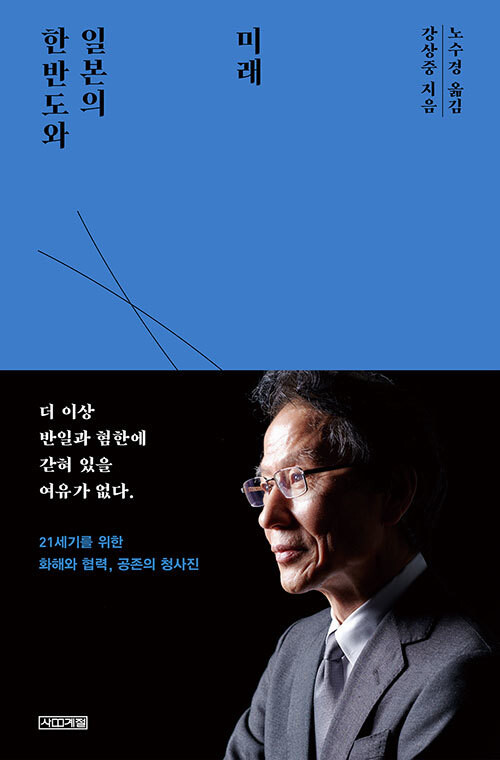

[Book review] Zainichi scholar urges S. Korea to enlist Japan as ally in Korean Peninsula peace process

“The Future of the Korean Peninsula and Japan” is a book by Kang Sang-jung, 71, a second-generation Zainichi Korean who lives and works in Japan. As a Waseda University student in 1972, he visited South Korea and gained a newfound understanding of his own identity, which led him to begin using his Korean name instead of his Japanese name.

After studying the history of political philosophy in Germany, he returned to Japan and became the first-ever Zainichi Korean full professor at the University of Tokyo. Since then, his trenchant analyses of Japanese politics have established him as one of his era’s leading critical intellectuals.

First published last year, “The Future of the Korean Peninsula and Japan” sees Kang exploring possible ways for South Korea and Japan to rescue their relationship from its severe deadlock. He writes from the perspective of a Korean in Japan who longs to see peace and reconciliation on the Korean Peninsula.

As a scholar who is active in Japan and communicates in Japanese, Kang shares a message with Japanese society, explaining why it is so important for Japan to mend its relationship with the Korean Peninsula. At the same time, he also shares a message to the South Korean government as an intellectual who identifies as Korean, arguing that Seoul cannot afford to allow relations with Tokyo to continue deteriorating if it hopes to make progress with peace on the peninsula.

The history of the “division system”He begins his book from a larger perspective, explaining how the “division system” that has persisted for over seven decades since the start of the Korean War has now reached the “beginning of the end.” That much was signaled by the three successive inter-Korean summits that took place in the wake of the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, along with the first-ever North Korea-US summit.

While Pyongyang and Washington have remained at an impasse ever since the collapse of their Hanoi summit in February 2019, Kang believes that from a broader perspective, the process of dismantling the division system has now reached a point of no return.

But when viewed narrowly in terms of relations between South Korea and Japan, the situation is one of persistent conflict that has left both sides suffering their worst mutual distrust and enmity since World War II.

In Kang’s assessment, there is a relationship between the two themes of the division system’s dismantlement and the souring of South Korea-Japan relations — if not an inevitable connection, then an undeniable structural association. In his book, he examines the geopolitical context behind the connection that formed between those two strands, as he seeks out possible ways for the two sides to escape their vicious cycle and restore a reciprocal relationship.

Before laying out his thesis, Kang offers a detailed look at the recent history in the Northeast Asian region that surrounds the Korean Peninsula. The starting point for his historical examination is the question, “Why is North Korea so fixated on developing nuclear capabilities?”

A look at the history of North Korea-US negotiations from the Bill Clinton presidency to the Barack Obama one shows that what Pyongyang has been looking for is not the possession of nuclear weapons per se, but assurances on its regime’s security.

The surest way for it to guarantee its regime’s safety would be for it to establish a peace agreement and diplomatic relations with the US. This explains why it held out such high hopes for the Donald Trump administration as it agreed to participate in a summit.

On the southern half of the Korean Peninsula, the most proactive supporters of North Korea-US negotiations before the Moon administration came along — and the ones who worked the hardest to improve inter-Korean relations — were the administrations of Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun. But this time period also overlapped with the arrival of hardline conservatives in the White House, which left North Korea-US relations in a stalemate.

Meanwhile, the Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye administrations that came after Roh undid all of the hard-won achievements in inter-Korean relations. It was only after the arrival of the Moon administration — 2018 in particular — that progress in inter-Korean and North Korea-US relations began to gather steam again.

As it happens, this period also coincided with the downward spiral in South Korea-Japan relations. Things had begun to sour during the Lee administration, and the chill remained through the Park presidency. But the descent of South Korea-Japan relations into their current, unprecedented mire of antagonism did not begin until 2018.

That year saw the disbanding of the “Reconciliation and Healing Foundation,” an organization established in accordance with a 2015 intergovernmental agreement on the Japanese military sexual slavery issue. It was also the year that the South Korean Supreme Court issued a ruling ordering a Japanese company to compensate victims of forced labor mobilization.

S. Korea should treat Japan as an ally when it comes to Korean Peninsula issuesThe biggest blow to South Korea-Japan relations came in the summer of 2019, when the Japanese government decided to remove South Korea from its “white list” of countries benefiting from expedited export procedures, and Seoul imposed its own retaliatory measures. Kang concludes that the Moon administration committed a clear diplomatic blunder by failing to work proactively to prevent relations from deteriorating to such a degree. To advance inter-Korean relations and promote North Korea-US negotiations, it needed to enlist the peninsula’s neighbors as cooperative partners — but according to the author, it showed immaturity in this regard.

Kang writes that Moon should not have forgotten the example set by the Kim Dae-jung administration, which visited Japan ahead of its inter-Korean summit to issue a joint partnership declaration with then-Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi, and treated Japan as an ally when it came to Korean Peninsula issues.

Feeling threatened by the growing closeness and cooperation between South and North Korea, then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe gave the impression of sabotaging it. It was up to Seoul to convince Tokyo that peace on the Korean Peninsula would benefit Japan, but there were not enough such efforts from the South Korean government.

“President Moon Jae-in needs Japan experts,” Kang asserts.

Japan needs to know that peace for Korea means peace for JapanHe also calls on the Japanese government to be more astute about reading historical trends. He suggests that as long as it persists in policies aimed at preserving the status quo — including the Korean Peninsula’s semi-permanent division — it could find itself confined to the periphery, without having the opportunity to contribute to peace in Northeast Asia.

In this context, he points out how Japan’s decision to take South Korea off of its white list came shortly after the leaders of South and North Korea and the US met at Panmunjom in summer 2019.

There were suspicions that Japan had abruptly dropped South Korea from its white list because it regarded the rapid progress in the Korean Peninsula peace process as a threat. Subsequent months showed that this hasty action only backfired on Japan. Kang argues that it’s not wise for the Japanese government to throw its support behind South Korea’s conservatives in an attempt to exploit internal conflict. Kang says that Japan should remember that the two countries enjoyed their best relationship in the postwar period under progressive presidents Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun, a relationship that was turned upside down by conservative presidents Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye.

The Japanese government is concerned that South and North Korea’s reconciliation and unification would bring the Korean Peninsula closer to China and have the effect of moving the armistice line into the Strait of Korea, but Kang says that such concerns are unfounded. Tied to the US for security reasons and to China for economic reasons, South Korea and Japan share the same geopolitical interests. Kang emphasizes that what Japan needs right now is a deep awareness that a solution to the North Korean nuclear issue and the normalization of relations between North Korea and the US would lay the foundation for peace in Northeast Asia and also lead to peace for Japan.

By Ko Myoung-sub, senior staff writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis![[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track? [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/1617144616798244.jpg) [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

Most viewed articles

- 1Under conservative chief, Korea’s TRC brands teenage wartime massacre victims as traitors

- 2[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 3Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 4Value of Korean won down 7.3% in 2024, a steeper plunge than during 2008 crisis

- 5[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 6First meeting between Yoon, Lee in 2 years ends without compromise or agreement

- 7Strong dollar isn’t all that’s pushing won exchange rate into to 1,400 range

- 8‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 9After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 10Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors