hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Salt in the wound: Chun’s 40-year legacy in Gwangju

An ill-fated relationship spanning more than 40 years bound the city of Gwangju and Chun Doo-hwan, who died Tuesday.

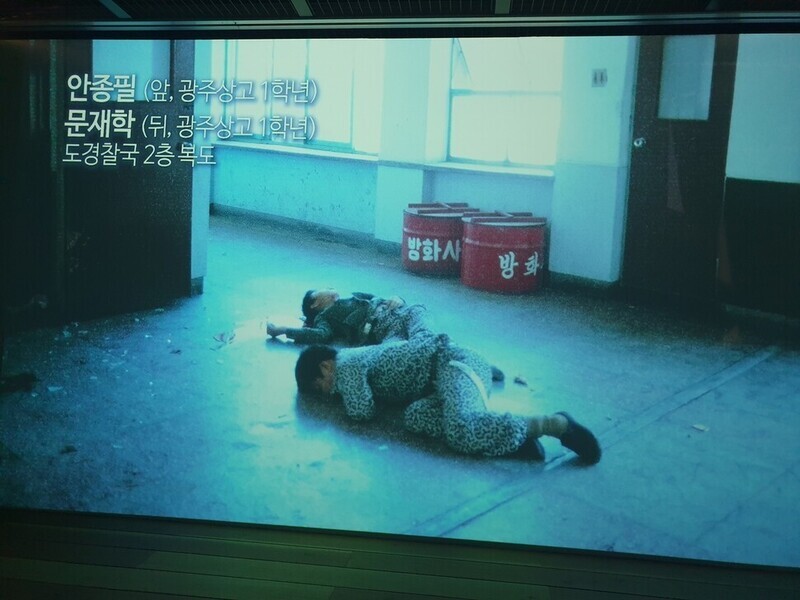

A total of 155 civilians were killed outright during the suppression of the Gwangju Uprising of May 18, 1980, by the “New Military” under Chun’s leadership. Another 110 died later from injuries, while 81 people were never heard from again.

An additional 2,461 people were injured, 1,145 were injured while in custody, and 1,447 were arrested and incarcerated. Those numbers, plus another 118 classified as “miscellaneous,” come out to 5,517 people who suffered grievously from the New Military’s abuses.

As commander of the Defense Security Command at the time, Chun was among five defendants convicted in trials related to the December 1979 coup and May 1980 massacre on charges of homicide with the intent to commit rebellion for their indiscriminate massacre of innocent citizens.

On April 17, 1997, the Supreme Court upheld all 13 of Chun’s convictions on charges including leading an insurrection, rebellion, and homicide with intent to commit rebellion. He was sentenced to life in prison before eventually being pardoned and rehabilitated.

Even after being legally reprimanded, Chun remained assertive. A case in point came with the April 2017 publication of his memoirs: writing about the events of May 1980, he said, “It has been shown that there was no deliberate and indiscriminate killing and injuring of civilians by the armed forces in Gwangju, and most of all that there was never any order to open fire.”

But this was false. The Supreme Court cited acts of killing and injury during the Gwangju reentry operation (“Operation Sangmu Chungjung”) as a basis for conviction on charges of homicide with intent to commit rebellion.

The Supreme Court concluded that Chun and the other defendants made the final decision at 12:01 am on May 27 to implement the operation in which commando units fired and killed 18 people early that morning. But unlike the district court, both the appeals court and the Supreme Court said that only the army operation to reenter Gwangju on May 27 could be regarded as homicide with intent to commit rebellion because of a lack of evidence. The killings that took place on other dates were regarded as crimes that occurred during the violent execution of the rebellion.

But the Supreme Court concluded that an “order to open fire” had been given during that process. “The defendants ordered the operation to proceed despite knowing that taking over the South Jeolla Provincial Office would require suppressing the armed protesters and that there would be casualties in the ensuing gunfight. They were obviously willing to order or tolerate homicide of this sort, and the order to carry out the operation obviously included an ‘order to fire’ in the sense that people could be killed in the scope of the operation,” the court said.

Chun was also convicted of rebellion for the killings that occurred while the military was violently suppressing the democracy protests in Gwangju in May 1980.

Chun didn’t stand before a court in Gwangju until May 3, 2018 — 38 years after the Gwangju massacre. He’d been indicted for defaming the memory of the late Rev. Cho Pius, who had witnessed martial law troops firing on Gwangju protesters from helicopters. In his memoir, published the previous year, Chun described Cho as “Satan in disguise.”

The district court sentenced Chun to eight months in prison, suspended for two years. Chun appealed the sentence and was awaiting his final hearing in the second trial, scheduled for Monday, Nov. 29.

Chun visited Gwangju during his tenure as president but didn’t receive a warm welcome. The Honam region in the southwest, which includes Gwangju, was the first place Chun chose to visit after being elected president in what is known as the “gymnasium election” by the National Conference for Unification, an electoral college, on Sept. 1, 1980.

Chun outraged citizens by peremptory remarks delivered during a visit to the South Jeolla Provincial Office on Sept. 5. “I’m satisfied that this was resolved through the unified effort of the Korean people. The Gwangju incident must not be talked about anymore,” he said.

“This region needs to regain its honor and dignity and serve as a model to other regions,” Chun also said during his visit.

Chun returned to Gwangju after being reelected president by the electoral college in January 1980 following a constitutional revision that limited the president to a single seven-year term.

When he visited the city on Feb. 18, a group of families of those who had been imprisoned after the Gwangju Uprising held a demonstration in front of the Gwangju YMCA. Chung Hyeon-ae — who would later serve as director of the May Mothers House — and other participants in the uprising and their family members chanted for Chun to release the people detained over the protests in Gwangju. Military tribunals held by the martial law command on Oct. 25, 1980, had sentenced five people connected with the uprising to death and seven to life in prison. Another 163 had been sentenced to prison and 80 had been given suspended prison sentences.

Chun made a third visit to Gwangju on March 10, 1982, but didn’t spend the night in the city. He and his wife stayed at Seongsan, a village in Damyang County, near Gwangju. The village leaders even erected a monument to honor the visit.

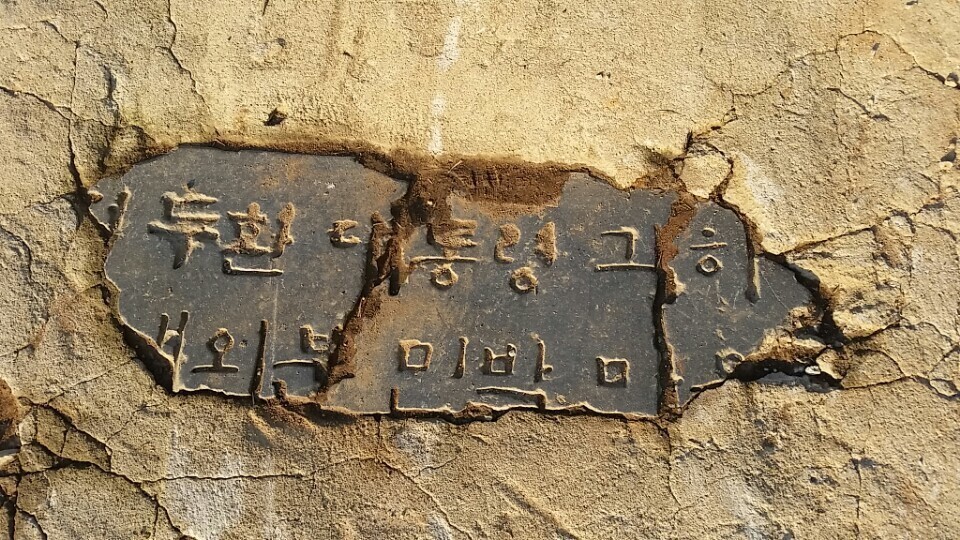

On Jan. 13, 1989, an association of people who’d taken part in the democratization movement in Gwangju and South Jeolla Province crushed that monument and buried it at the entrance to the cemetery in Gwangju’s Mangwol neighborhood where the victims of the massacre were buried. A plaque by the monument says, “Please walk over this monument to appease the vindictive spirits of those who died in the Gwangju massacre.”

This is the monument that Lee Jae-myung and Sim Sang-jung, presidential candidates for the Democratic Party and the Justice Party, reportedly walked over recently.

By Jung Dae-ha and Kim Yong-hee, staff reporters

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

Most viewed articles

- 1Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 2Trump asks why US would defend Korea, hints at hiking Seoul’s defense cost burden

- 3[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- 4At heart of West’s handwringing over Chinese ‘overcapacity,’ a battle to lead key future industries

- 5[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 61 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 7Fruitless Yoon-Lee summit inflames partisan tensions in Korea

- 8First meeting between Yoon, Lee in 2 years ends without compromise or agreement

- 9Under conservative chief, Korea’s TRC brands teenage wartime massacre victims as traitors

- 10[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol