hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

One year into his term, S. Korea’s Yoon Suk-yeol only has eyes for US, Japan

“Taking sides” has been a running theme in assessments of the Yoon Suk-yeol administration’s foreign affairs and national security policies in the year since it took office.

The pronounced divisiveness in domestic affairs has been carried over into the diplomatic realm. Yoon has consistently emphasized a binary “good vs. evil” attitude toward international affairs, which he has viewed as a confrontation between a South Korea, US, Japan bloc on one side and a North Korea, China, and Russia bloc on the other.

The typical understanding of international relations is that it is an area where the national interest is paramount and there is no such thing as an eternal friend or enemy.

Yet Yoon has described the South Korea-US relationship as an “alliance rooted in the universal values of liberal and democracy and the market economy, rather than a matter of coming together or drifting apart based on our interests.” He has upgraded the status of the alliance with the US to that of a sacrosanct “values alliance.”

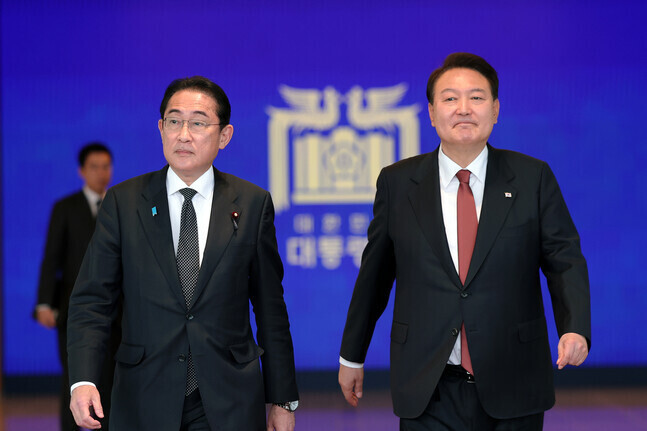

In emphasizing the strategic importance of the Indo-Pacific region following their summit on Sunday, the South Korean and Japanese leaders signaled their intention of containing China. In the area of foreign affairs, Seoul has effectively crowded out or erased Beijing and Moscow, leaving only Washington and Tokyo.

In the process, the administration has run into critics who decry the “indignity” of Seoul emphasizing the importance of the South Korea-US alliance even after the disclosure of documents showing eavesdropping by the US — or of it letting Japan off the hook for refusing to acknowledge the damages of forced labor mobilization by insisting that “matters of historical perceptions are not an area where you can make unilateral demands of the other side.”

In the cases of Russia and China, the administration has been needlessly provocative on matters that those two countries are enormously sensitive about — namely, lethal weapons aid to Ukraine and statements about Taiwan. Yoon’s misstatements have come up for repeated criticism.

Summits lead to increased trilateral coordination to contain ChinaThe foundations for trilateral security cooperation with the US and Japan to contain China have been laid through numerous summits, including a May 2022 South Korea-US summit held shortly after Yoon took office, a trilateral summit in Phnom Penh last November, bilateral South Korea-Japan summits in March and May, and another South Korea-US summit in April.

These meetings followed the US foreign affairs and national security frames to the letter.

The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), a US economic vision, was a key part of the agenda for the first South Korea-US summit, and discussions also took place on Seoul’s cooperation with the Quad, a security framework in which the US and Japan are participating alongside India and Australia.

The statement issued after the trilateral summit in Phnom Penh last November contributed to beefing up their security collaboration with an agreement on the real-time three-way sharing of North Korean missile warning data.

Two days after that statement came out, Yoon had his first bilateral summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping during the Group of 20 summit. But Xi did not take up his request for China to “play more of a role” on the North Korean nuclear issue.

South Korea’s summits this year with the US and Japan have also more clearly revealed the framework of antagonism between South Korea, the US, and Japan on one side and North Korea, China, and Russia on the other. The center of gravity in South Korea’s diplomacy has veered sharply from “strategic ambiguity” to “strategic clarity.”

During the South Korea-US summit in April, the leaders agreed to work with the US exploring ideas for joint maritime exercises. Citing the return of “shuttle diplomacy” with Japan as an achievement, Yoon opened the way for increased trilateral security cooperation by saying that he would not “rule out Japan’s participation” in South Korea-US discussions on increasing extended deterrence.

Seoul National University professor Nam Ki-jeong describes this trend as a “process of [South Korea] being drawn into the international order devised by the US to contain China.”

He went on to predict that trilateral security cooperation would “allow Japan to increase its influence on the Korean Peninsula.”

“With the latest summits, both the US and Japan got what they wanted, up to and including a resolution of historical issues, but it’s not clear whether this accords with South Korea’s national interests and security,” he said.

“Our diplomatic space has shrunk,” he added.

Weapons aid to Ukraine and cross-strait relationsRussia and China have grown more distant from South Korea over the years. Reading the historical currents with the imminent end of the Cold War era in the late 1980s, the Roh Tae-woo administration adopted the Nordpolitik approach, declaring that Seoul was “heading beyond Beijing and Moscow to Pyongyang.”

But now the Nordpolitik achievements by conservative administrations are being upended.

Since the start of the war in Ukraine, South Korea had adhered to the principle of not supplying aid in the form of lethal weapons. But in a Reuters interview published on April 19, Yoon said, “If there is a situation the international community cannot condone, such as any large-scale attack on civilians, massacre or serious violation of the laws of war, it might be difficult for us to insist only on humanitarian or financial support.”

His remarks hinted at the possibility of Seoul providing “other means” of support. Russia immediately responded with vehement objections, asking how the South Korean public would react if Moscow were to provide weapons to North Korea.

In the same Reuters interview, Yoon drew an analogy between inter-Korean relations and relations between China and Taiwan across the Taiwan Strait.

“These tensions [in the Taiwan Strait] occurred because of the attempts to change the status quo by force, and we together with the international community absolutely oppose such a change,” he said. China also reacted with vehemence, harshly denouncing the remarks as meddling in “internal affairs.”

Many are voicing worries that the overwhelming diplomatic focus on the trilateral relationship with the US and Japan could be a risk factor worsening instability in the Korean Peninsula’s political situation.

“If we’re going to abandon strategic ambiguity in favor of ‘clarity’ in East Asia, that needs to be backed up with diplomatic skill and power,” said Moon Heung-ho, a professor at the Hanyang University Graduate School of International Studies.

“The US itself has long practiced a strategic ambiguity approach in its policies on Taiwan. In a situation where our inter-Korean and South Korea-Japan relations are both unstable, there’s a serious danger of this ending up damaging for us,” he predicted.

“Biden” and “UAE/Iran” gaffesWorries about Yoon’s diplomatic inexperience have been exacerbated by the gaffes and crude language that have popped up with seemingly every overseas visit.

Following a brief conversation with US President Joe Biden while he was in New York to attend a UN General Assembly meeting last September, Yoon was caught on a hot mic making a remark as he exited the event.

“What an embarrassment for Biden if these [expletive] refuse to approve it in parliament,” he appeared to say.

Afterward, the South Korean presidential office insisted that the quote had been misheard. The remark had not included the words “for Biden,” it said, but a somewhat similar-sounding Korean word meaning “if they ruin things.”

Yoon also drew a heavy backlash from Iran with remarks he made while meeting in January with Akh Unit troops deployed to the United Arab Emirates.

“The UAE’s enemy — the country posing the biggest threat — is Iran, and our enemy is North Korea,” he said at the time.

By Jang Ye-ji, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

Most viewed articles

- 1New sex-ed guidelines forbid teaching about homosexuality

- 260% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 3Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 4Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 5[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 6S. Korea discusses participation in defense development with AUKUS alliance

- 7OECD upgrades Korea’s growth forecast from 2.2% to 2.6%

- 8Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 9Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 10Opposition calling for thorough investigation into Pres. Park’s unelected power broker