hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

New eyewitness testimony debunks Chun Doo-hwan’s myth of “self-defense” in Gwangju

“I can still see that soldier with his upper body raised as he coughed up blood from his mouth.”

Speaking with the Hankyoreh on May 8 in his office in Gwangju’s Buk (North) District, the 64-year-old surnamed Cho said he has never forgotten the sight of the horrific injuries suffered by a martial law soldier in front of the former South Jeolla Provincial Office nearly 43 years ago on May 21, 1980.

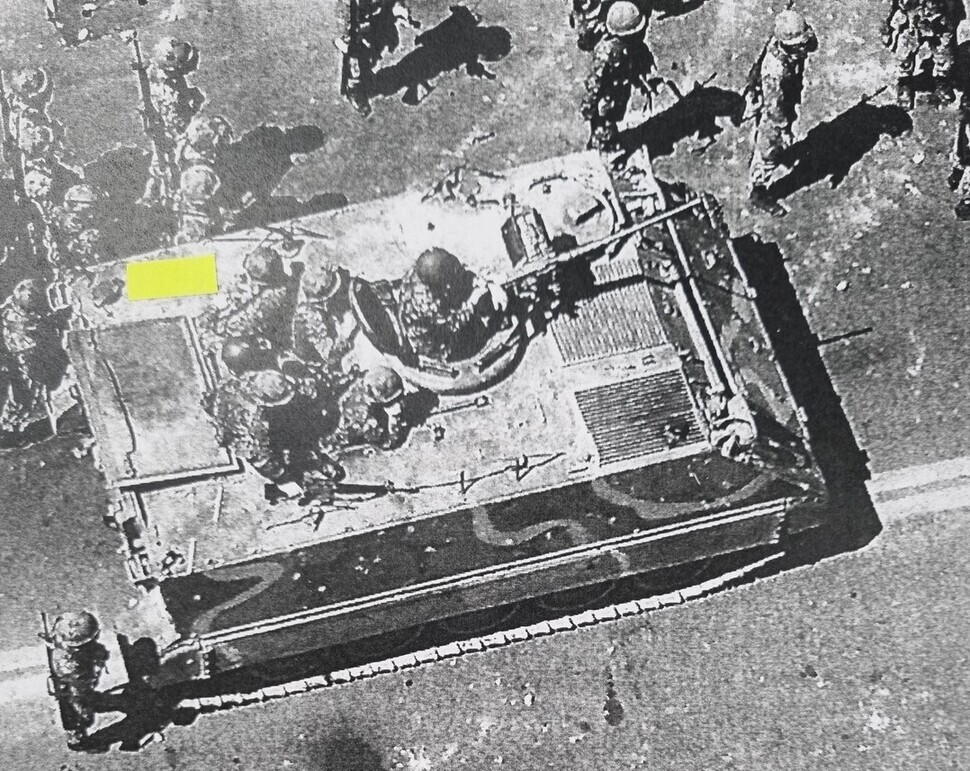

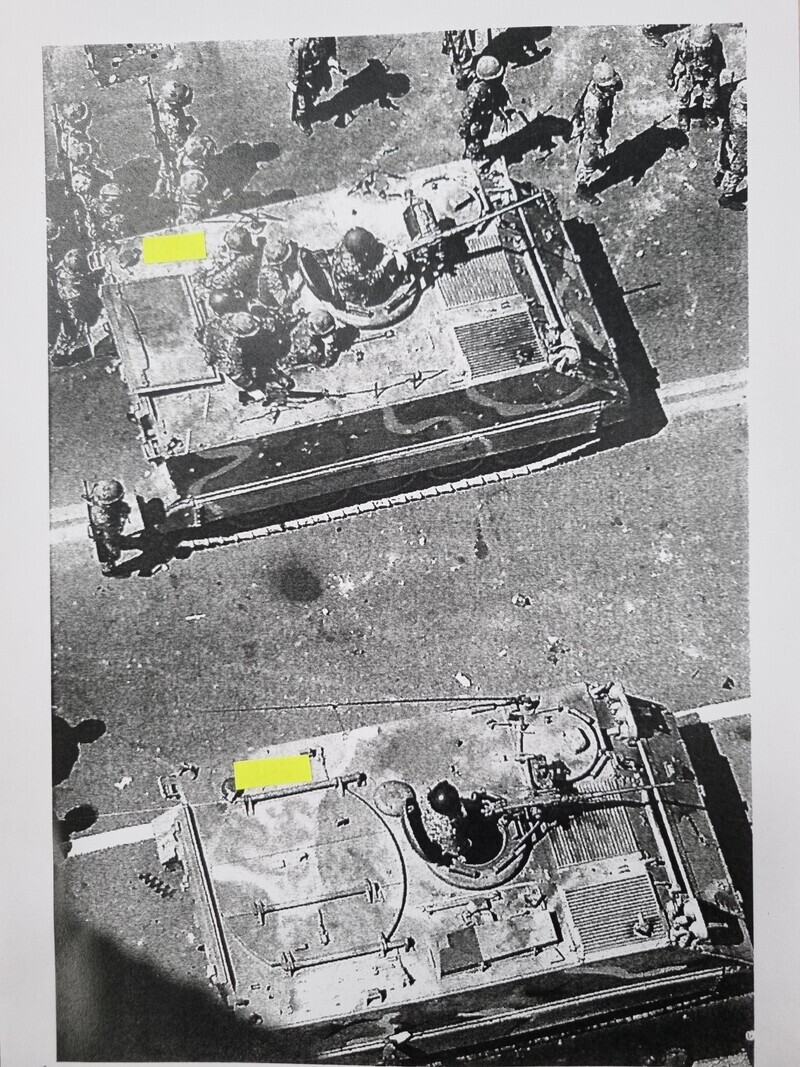

He explained that he was aware of the details of the incident because of his position driving an armored car carrying members of the public at the very front of the demonstrators’ procession. His is the very first eyewitness account from one of the people driving an armored car for the demonstrations just before the martial law troops opened fire in front of the provincial office on May 21.

“As the citizens and martial law troops faced off, some of the university students who were in the armored vehicle yelled, ‘Push, push,’ and after a bus that was next to us moved forward first, I moved the armored car up about 5 meters,” he recalled, explaining that it “was not very fast because the vehicle was so heavy.”

“One of the martial law forces’ armored vehicles in front of us backed up, and a soldier who was to the right of it [from Cho’s perspective] ended up with his lower body crushed under its track,” he remembered.

His eyewitness account is important in showing the falsehood of claims by Chun Doo-hwan and others that the decision to open fire on the public in front of the provincial office on May 21, 1980, was an “exercise of self-defense” in response to a martial law soldier being killed by the demonstrators’ armored vehicle.

Jee Man-won and other far-right commentators have claimed that the fact that citizen forces were driving military armored vehicles is evidence that North Korean special forces were involved in the events in Gwangju.

At the time, members of the public were using buses and trucks to push the martial law forces from in front of the Jeonil Building toward the provincial office.

The armored vehicle that Cho was driving was a wheeled CM6614 carrier model brought by citizens from an Asia Motors (Kia’s previous incarnation) factory. It was different in appearance from the caterpillar-track M113 and M125 armored carrier models used by the martial law troops.

The martial law forces, who had been given live ammunition before the incident, opened fire on demonstrators with M16 rifles and 0.50-caliber machine guns mounted on the armored vehicles.

“After the incident, bullets started flying,” Cho recalled.

“In my terror, I fled around the fountain and toward the Chonnam National University Hospital, so I don’t know about what happened in front of the provincial office,” he added.

In 1980, Cho’s work involved using a Pony wagon to deliver packaging from a factory at the Gwangcheon Industrial Complex to a Youngil Foods factory in the Unam neighborhood of northern Gwangju’s Buk District. After earning his driver’s license in 1978, he had decided he wanted to become a cargo truck driver and was gaining experience with baked goods packaging deliveries, while occasionally riding in the passenger seat of an 8-ton truck.

While he does not recall the exact date — which may have been around May 18, 1980 — he ended up taking part in demonstrations after an episode when he delivered Pagoda-brand bread from Youngil Foods to combat police in front of the provincial office during the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement.

“As I was leaving after delivering the bread, the combat police handed me a box of tear gas canisters and said, ‘We have to retreat now. The bread factory is near the headquarters, so if you put these there without the citizens knowing, we can go get them later.’”

“I was on my way back toward the banks of Gwangju Stream when the soldiers stopped the car and started beating me up. They pointed at the tear gas canisters and said, ‘Did you steal these?’” he remembered.

“By the time I explained the situation and got out of there, I was bloodied all over,” he added.

Parking the Pony in front of his boss’s house in the city’s Hwajeong neighborhood, Cho took the rest of the day off without leave and joined the demonstrations. His motivation was a sense of rage over what had happened, he explained.

“I visited a side street by the Army Gymnasium [Sangmugwan] building and the Gwangju Dongbu Police Station, and they had an armored vehicle parked there. The university students were looking for someone to drive it,” he said.

“I’d driven an 8-ton truck before, so I said I’d give driving an armored vehicle a try,” he continued. The driver’s seat turned out to be similar to a regular truck’s, he said, adding that the only difference was the shape and position of the shift lever.

“Other than the narrow field of vision, the armored carrier was pretty straightforward to drive,” he recalled.

“Mostly, I would drive around the periphery to places like Hwasun [County], Gwangju Detention Center, and Songam [a neighborhood in Gwangju] picking up wounded or dead civilians and transporting them toward the provincial office,” he explained.

Over and over, he made trips carrying two to five passengers at a time. Due to the lack of interior space, he sometimes had to stack bodies vertically; even today, he feels sorry about it.

With every evacuation, there was the constant sound of bullets pounding against the vehicle. When Cho said he was too afraid to continue, the passenger next to him — a university student two years his senior, whose name was either “Gwang-su” or “Gwang-hee” — persuaded him to stay, asking, “Who will drive the carrier if you’re not here?”

When he got out at the provincial office to briefly visit the bathroom, the university student citizen soldiers stayed close by him for fear that he might disappear.

After facing unusually heavy fire from the direction of Songam, Cho dropped a patient off at Kwangju Christian Hospital, stopped the vehicle, and jumped out. He was subsequently apprehended by the martial law troops and taken to the Sangmudae (combat training command) brig. But his wrist was dislocated during his arrest, and when he demanded treatment, he ended up simply being released.

Today, Cho runs a small business. Over the past four decades, he has kept quiet about his role in the demonstrations for fear of possible negative repercussions.

But after far-right commentators began referring to the citizen forces’ armored carriers as “evidence” of infiltration by North Korean special forces, Cho contacted the May 18 Foundation in 2020 and volunteered to go on record about his carrier-driving experiences.

“Anyone who knows how to drive a truck can drive a wheeled armored carrier,” he said.

“Until the distortions of the truth stop, May 18 will never be over,” he stressed.

Cha Jong-su, director of the May 18 Foundation’s archiving and truth department, said, “Chun Doo-hwan waged a legal battle against May 1980 groups after claiming in his memories that [the martial law forces] ‘opened fire when a citizen army armored carrier crushed a soldier to death,’ and that case is currently pending in the Supreme Court.”

Referring to Cho’s eyewitness account, Cha said it was “significant testimony that could break down the argument that the martial law forces were ‘exercising their right to self-defense.’”

By Kim Yong-hee, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 3Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 4[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 5Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 6Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 7S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 8[Column] Unsettling moves by the UN Command lay way for Korean involvement in Taiwan

- 9[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 10[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol