hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Working across borders, to preserve voices and stories of Korea’s “comfort women” in English

On May 17, the 1596th Wednesday Demonstration, organized by the Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan was held in front of the former Japanese Embassy in Seoul’s Jongno District.

As of 2023, the weekly demonstrations have been going on for 31 years since the first was held in January 1992. Students from Sungmisan School, an alternative school in Mapo District, Seoul, also participated. The children spoke words of solidarity, saying, “Even beyond the issue of comfort women, we are against all sorts of discrimination, oppression, and violence against minorities.”

They also sang the staple songs of the demonstrations: “Like the Rock” and “A World as Good as a Song.” Students from Madras Christian College in Chennai, India, also participated in the rally. They were on a 10-day trip to South Korea to “learn about Korean history and democracy.” The Indian youth had visited the May 18th National Cemetery in Gwangju the day before and joined everyone else in the rally by singing “March for the Beloved.”

At the same time, on the opposite side of the road, members of a right-wing group held a disruptive counter demonstration, chanting slogans such as “Comfort women are frauds,” “Not a single comfort woman was forcibly taken,” and “Arrest Yoon Mee-Hyang!” referring to a former lawmaker who was found guilty of embezzling donations for comfort women.

The banners were littered with wild claims such as “Anti-American and Anti-Japanese sentiments are spread by the North Korean government,” and “Comfort women were nothing more than prostitutes.”

This shows the reality that comfort women face, a reality that gives a voice to those who deny historical facts. This also demonstrates that the resolution to past historical issues will not be easy to achieve, and why this issue is so important and urgent.

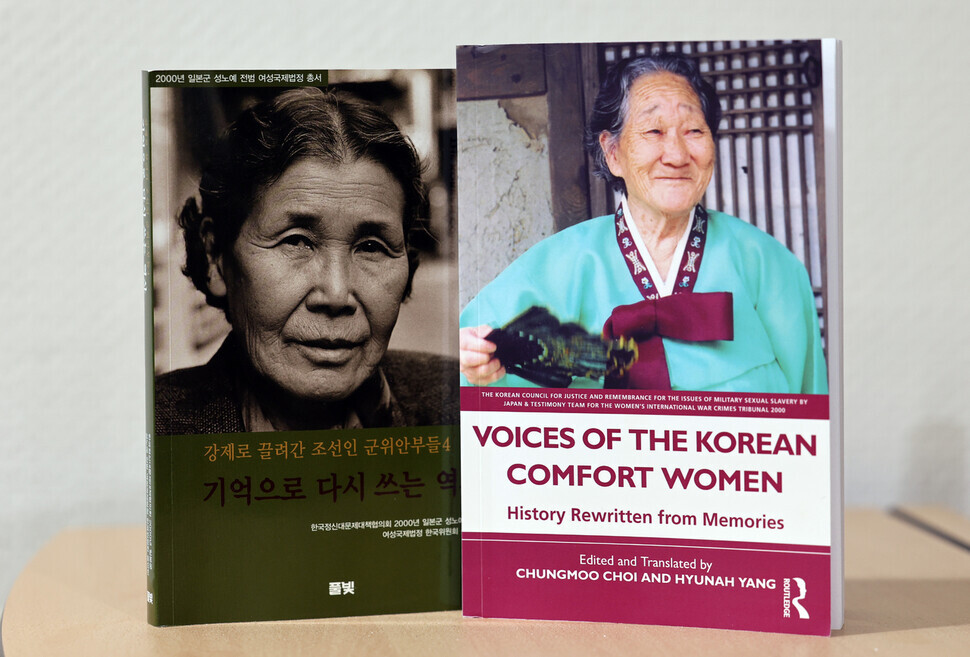

In the midst of this chaos, an English translation of comfort women’s oral testimonies has been recently published. Published by a global academic publisher in the United Kingdom, it is titled “Voices of the Korean Comfort Women.”

It is based on the 2011 revised edition of “Korean Military Comfort Women 4: Rewriting History through Memories,” written by a research team led by Yang Hyun-ah, a professor specializing in sociology at Seoul National University School of Law.

Yang led the testimony team under the Korean committee of the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery in Tokyo, Japan, in December 2000, and recorded the oral histories of survivors of the system.

The Hankyoreh met with Yang at Seoul National University after covering the Wednesday Demonstration on May 17 to talk about the process and importance of publishing the book in English, as well as the realities and challenges of the comfort women issue.

Also interviewed were Choi Ki-ja, the director of the Institute for Gender Education (IGE), who was a graduate student of Yang’s and served on the testimony team at the international tribunal in 2000, and Kim Soo-ah, a professor at Seoul National University’s Department of Communication (Interdisciplinary Program in Gender Studies).

“We had been planning to translate the testimonies of the grandmothers into English for a long time, but it was delayed for quite a while,” said Yang, who likened the catalyst for the English publication to a symbiotic match of internal and external forces.

“After the women’s tribunal in 2000 and especially in the 2010s, the importance of recording and translating comfort women’s testimonies into English grew. Although various scholars and organizations such as the Korean Council encouraged us to go forward with the project, we were unable to do so due to scheduling issues and other variables,” she said.

“There are many dialects and vernacular words that the survivors use that are difficult for even Koreans to understand, and it was not easy to find someone who was knowledgeable on the comfort women issue and current events and was fluent in both English and Korean so as to translate the testimonies into English,” Yang added.

Then, in 2018, Choi Chungmoo, a professor of East Asian studies at the University of California-Irvine, in the US, approached her about researching gender issues in Korea.

“I thought, ‘I can’t miss a good Korean Studies scholar like Choi who is fluent in both languages,’ and I thought that we would end up with a great translation if we worked together,” Yang said with a laugh.

As such, translation and editing teams were formed across the Pacific Ocean in both the US and South Korea. The US translation team included Choi and seven young researchers from various fields of study, including East Asian regional studies, Korean literature and popular culture, Japanese literature, media, gender studies, and women’s studies.

The editing team was composed of three Koreans, including Yang, and two Americans, UC Irvine Korean studies professor Kim Kyung-hyun, and second-generation Korean American film expert Zury Lee.

The Korean editing team was “deeply attached to the survivor’s testimonies” as the members had also been part of the war crimes tribunal testimony team in 2000. Despite their attachment, the translation process was not easy.

The differences in language structure between Korean and English are significant, and the grandmothers’ oral histories were characterized by word omissions, their memories often jumped across time and space, and many details required fact-checking. There were also many ungrammatical inscriptions.

It was essential to understand the “context” rather than the “text.” Words that were omitted were placed in square brackets, descriptions of gestures and facial expressions or brief comments were inserted in single brackets, and passages that required detailed background explanations were annotated individually. Yang recalls the challenge.

“The biggest temptation we faced when we created the Korean version of the testimonies was the urge to make the testimonies easier for the reader to understand. But, if you turn the spoken word into smooth sentences, it becomes our [the testimony team’s] language, not theirs,” she said. “We wanted to connect the reader to the survivors’ language, and not only that, but we wanted to act as a mediator, a bridge, to convey the physicality of the survivors, their emotions, their language, and their cognition. We wanted to intervene as little as possible.”

The time difference between South Korea and the US also proved to be a challenge.

“There were many days we couldn’t sleep because we were in completely opposite time zones. When a translation came in from the US team in the middle of the night, the three of the editing team in Seoul would have to open the same Google Doc file at the same time, and we would exchange opinions through text messages on our phones,” Yang shared. “There were many times when we couldn’t immediately judge a draft translation, so we would review it first in Korea to see if the wording was right, and then we would do a full review with the US editing team.”

In 2019, the team organized bilateral workshops in the US (June) and Seoul (August) as a process of reconciling different opinions on the wording and method of translation.

“In Korean, even if a word is omitted, it can be understood from the context, but in English, it is difficult to clearly indicate the subject and tense,” says Choi.

“For example, one of the oral accounts would just say, ‘The soldiers lined up. They tested for STDs. But our translation team in the US would translate that as, ‘The soldiers lined up for an STD test.’ There was a debate about whether the people being tested for STDs should be ‘they,’ or ‘I’ or ‘we’ to include the grandmother telling the story. There were some missteps in the first draft of the translation when young translators didn’t grasp the overall situation or context,” said Choi.

A bigger challenge was how to accurately render regional dialect, distinctive cultural concepts, and Korea’s unique flavor into English.

“When the grandmothers talked about buying rice, they would use an expression that literally means ‘selling rice.’ Our young translators in the US sometimes mistranslated that as ‘sell,’” Choi said, referring to a relatively mild translation crux.

“A grandmother from Jeolla Province referred to a certain place as ‘Haesamuri,’ which we had to leave in the text as is because even Jeolla locals didn’t know what it meant. But in the original draft we got from our translators, someone had rendered that as ‘seafood’ [in Korean, ‘haesanmul’].” That got a chuckle from everyone present.

The editing team — the people who had transcribed the oral accounts themselves — identified two principles for the English translation.

“We tried to preserve the oral flavor of the accounts as much as possible. That’s probably the biggest difference with previous translations,” Choi said.

“Another principle was readability. English-language readers need to be able to understand sentences that aren’t even easy in the original Korean,” Yang remarked.

“We wanted a translation that captured the sincerity of the grandmothers’ stories while also accurately conveying the meaning, and the number of people capable of doing that was quite limited,” Choi explained.

Yang described the process as follows. “One English speaker would say, ‘That kind of translation isn’t English; I can’t understand it.’ But another would say, ‘What do you mean? I can understand it just fine.’ So there was a difference of opinions. We did our best to find a compromise.”

“I realized this is the kind of challenge involved when ‘locally’ produced information is made available to ‘global’ readers, and when Korean content is disseminated around the world,” she added.

The translation and editing teams managed to make the most of their respective expertise and strengths through close communication, resulting in English sentences that captured the unique linguistic sense of Korean.

One example was this sentence from the oral account by Choe Gap-sun.

Korean: “Geureondi [goja yeonggameun] eodi gattdaga tilleungtilleungtilleung waseoneun, […] aigu, jigeu eomaega jukeo nongerong.”

English: “But then [this impotent old man] went somewhere else and came trot-trot-trotting back, (…) aigoo~ now that his mom was dead and gone.”

“The relationship between the editing team and the translation team went beyond a mere division of labor. It also signified passing the torch for [the grandmothers’] testimony from one generation to the next,” Yang said.

“The Korean oral testimony team I led during the International War Crimes Tribunal was composed of university students in their 20s. Now two decades have passed, and the Americans on the translation team are young people who are currently completing or have just completed their doctorates. They hail from a wide range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds: Korean, Chinese, Japanese and American.”

“The interest they’ve taken in the comfort women issue and the expertise they’ve gained will enable them to stay involved in this sort of research in the future,” she added.

But the fact is that the Yoon administration has been rapidly moving Korea-Japan relations in an ahistorical direction, setting aside human rights, with an eye to a potential trilateral alliance with the US. That’s a major obstacle to resolving historical disputes dating back to Japan’s colonial rule over Korea and achieving justice and healing for the survivors.

“President Yoon said Korea won’t accept further claims for damages and will absolve Japan of responsibility for forced labor during the colonial period through what he calls ‘third-party repayment,’ which amounts to Korea paying the victims itself. But Yoon dispensed with decent communication with the victims in a violation of international norms,” Yang observed.

“This really drove home that the Yoon administration is willing to disregard justice and treat the ordinary people’s pain as a bargaining chip for foreign relations.”

All the surviving comfort women are now advanced in years, well past 90 years old. On May 2, another one of the grandmothers passed away. That reduced the number of survivors to nine from the 240 former comfort women who originally registered with the Korean government.

Far-right groups not only in Japan but also in Korea deny the compulsory nature of the comfort women’s recruitment and seek to spin false narratives. That’s why it’s so important to ensure that those events are properly remembered, recorded and taught to future generations.

“Undergraduates seem to struggle with the comfort women topic when it comes up in their courses. Because the current debate over the comfort women focuses on whether their recruitment was compulsory or not, students are only curious about that and are reluctant to read their testimonies,” said Kim Soo-ah, the Seoul National University professor.

“A group of researchers and activists who focus on the comfort women issue are exploring the option of creating a program for educating high school students about this issue from a postcolonial perspective,” Kim added.

“For the time being, there’s little chance of these historical disputes being resolved through smart negotiations with Japan. We shouldn’t expect much from the Japanese government,” Yang said.

“What’s ultimately important is the role played by civil society in Korea and Japan and solidarity between them. We also need to be active at the UN and in international human rights organizations and elevate Korea’s status and position there.”

Yang also noted the importance of media content that can raise awareness of the truth and help achieve justice. “We have no choice but to build coalitions and create knowledge and discourses in various areas, including the law, literature and records.”

“We’re hopeful that there will be more venues for discussing wartime sexual violence and human rights in the future. I suppose that hope is why we keep doing projects of this sort,” she said.

By Cho Il-joon, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 4[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 5Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 6[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 7[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 8[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 9Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 10Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?