hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

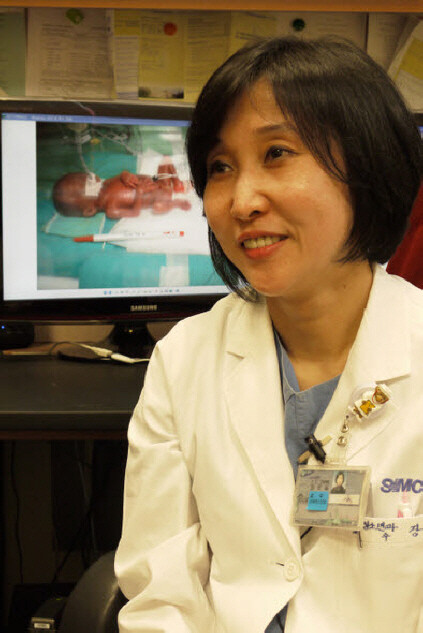

Miracle baby’s doctor says teamwork trumps technology

By Kwon O-sung

380g is even lighter than two 200ml milk packs. Until now, it had been considered impossible for newborns under 400g to survive. How was the “380g Miracle” possible?

The heroine of this story, Samsung Medical Center’s Jang Yun-sil, met with the Hankyoreh at the hospital Friday. The team of Jang and Dr. Park Won-sun turned little baby Eun-sik, South Korea’s premature baby at 380g, into a healthy baby of 3.6kg in just nine months.

“Eun-sik was able to survive not due to the development of some revolutionary piece of medical technology, but rather use of all the techniques and concentration we have developed until now,” said Jang. This is to say, the deciding factor was not technology, but all-out-effort.

“A premature baby’s skin is like that of an adult who has suffered a third-degree burn. If you lose even the slightest focus, the skin can be easily hurt and there is the threat of infection,” said Jang.

The intensive care room for newborns visited during the interview process was very hot. This is because the temperature was set for nearly 36 degrees for the babies. Every act in the room was taken carefully.

“Like in football, teamwork is central to caring for premature babies,” Jang stressed. “This is not something one person can do - if one person makes the slightest mistake, from the doctors and nurses to the cleaning people and suppliers, it could be fatal.”

Four days after he was born, Eun-sik needed to receive a heart operation. Because doctors cannot bring a newborn weighing less than 400g into an operating room, the operating team and all the implements needed to be brought into the newborn intensive care room.

According to Jang, life for the newborn treatment team is hellish.

“It is a department people avoid,” she said. “Because team members be prepared for anything to happen 24 hours a day, there are countless times you cannot go home.” Even her colleagues at the relatively hard-working hospital ask why she lives that way.

The premature infant survival rate in South Korea is much lower than that in developed countries. Another problem is that no countermeasures were taken even though the premature birth rate increased greatly from 2.7 percent in 1993 to 4.9 percent in 2009. This increase is due to mothers’ birth ages increasing as the marriage age increases.

“The number of premature infant intensive care rooms, however, is greatly decreasing,” she said. “A worrisome situation has developed with even the collapse of the premature infant care system in the provinces.” That doctors and nurses are manning their posts in the newborn care room despite such tough conditions is due to a sense of worth and duty. Jang, a graduate of Seoul National University’s medical school, has focused on newborn care since becoming a fellow in 1994 because she is moved every time she sees the face of baby who grew up well.

“The baby I remember the most is Joseph Cameron, born in 2006,” said Jang. “Born to American parents serving in the U.S. military in Korea, he was the first infant born at 22 weeks that I saved.”

Jang added, “Caring for premature infants is always like going somewhere new.” She smiled brightly as she looked at a photo of a healthy Joseph sent by his mother from the United States.

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 9[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 10[Editorial] Government needs to stop impeding Sewol mourning