hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

South Korea’s own Watergate

Illegal surveillance scandal by MB administration similar to case that led to US president’s resignation

By Yeo Hyun-ho, senior staff writer

The civilian surveillance scandal now being revealed in South Korea is reminiscent of Watergate in various respects. First, it is an organization that is responsible. A number of the parties who broke into the US Democratic National Committee offices in the Watergate Arms building in Washington, DC, in May 1972 were members of a special White House investigation team launched in July 1971. The so-called “plumbers” were a product of the paranoia of then-president Richard Nixon and his associates, who attributed the struggles in the 1968 presidential race to “administration enemies,” including Vietnam War opponents and civil rights activists.

The organization was mobilized to monitor these groups, with the plumbers taking on the unsavory tasks that the official intelligence agencies wouldn‘t touch, such as illegal eavesdropping.

The public ethics division in South Korea’s Prime Minister's Office, which carried out the surveillance, was launched in July 2008 at the end of the candlelight vigils against US beef imports, a traumatic experience for the Lee Myung-bak administration. The thousands of targets appeared to share the one common trait: being potential “enemies of the president.”

Also similar was the incident that triggered the public controversy. The Watergate plumbers were indicted for breaking and entering, and at their sentencing session on Mar. 23, 1973, the judge read a letter sent to the court by one of the accused, James W. McCord, Jr. In it, McCord accused the White House of directing the cover-up and pressuring the parties involved to keep quiet. The Nixon administration was forced to submit to a reinvestigation.

Similarly, in South Korea, the reinvestigation of the surveillance case began when Jang Jin-su, a former public ethics division officer indicted in the case, blew the whistle on attempts by Blue House officials to keep the parties quiet ahead of a Supreme Court ruling on his case.

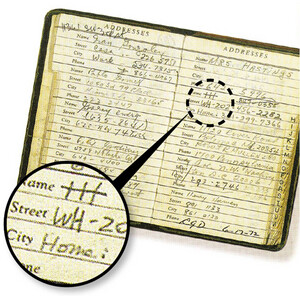

There is not yet any way of knowing what other similarities will later be uncovered, but the evidence that has surfaced so far gives a clear picture of the situation. Just as evidence of the Watergate cover-up was captured on reams of White House cassette tapes, the attempted evidence destruction and silencing in the surveillance case are captured on dozens of hours of recordings. The details of the far-reaching illegal monitoring are also presented in detail on more than 20 thousand pages of documents. At this point, it is difficult to argue that this represents just the tip of the iceberg. Judging solely by the investigation, the case appears to be in the bag.

There is, however, a stumbling block. Nixon dismissed special prosecutor Archibald Cox in an attempt to halt the investigation before it reached him. It was a case where the target of the investigation was the very person with authority to appoint and dismiss special prosecutors. That risk is present in the Korean case as well. Justice Minister Kwon Jae-jin, the head of the judicial affairs and prosecutors, was senior secretary for civil affairs at the Blue House at the time of the silencing attempts. And the individual with authority to appoint and dismiss prosecutors is Lee Myung-bak, who will at some point have to answer questions about whether he received reports on the illegal surveillance findings or took part in the effort to keep the situation quiet. Either way, getting the figure with authority to do something potentially devastating to himself will be no easy matter.

There are already grounds for questioning whether the investigation has been distorted. Prosecutors carried out an investigation on Jang, the whistle blower for the cover-up, by conducting a search and seizure on his effects in what some critics are contending is an attempt to establish a link with “subversive political elements.”

Prosecutors searched Jang’s house, after he blew the whistle on the cover-up.

There may have been political considerations. Campaigning for the April 11 general election began a few days ago. The investigation is still in its early stages, but it has been very cautious. Previously, prosecutors were reluctant to reopen the case even after new and decisive evidence surfaced, claiming that they wanted to wait for an accusation. Did they feel burdened by a politically explosive case?

By next week, the prosecutors‘ reinvestigation will be at a crossroads. In the face of a mountain of evidence, they will either waver and watch for cues like the first investigation two years ago, or go ahead and brave their way through. Immediate issues include resolving who was responsible up the line from former Blue House administrative officer Choi Jong-seok and former secretary Lee Young-ho, along with the source of a sum of around 100 million won (US$88,343) that was reportedly given to Jang to keep him quiet. The Watergate episode went into full swing after tracking of checks held by the plumbers were disclosed to the Nixon’s reelection committee.

The prosecutors are reportedly determined to carry on with the investigation, working each day until 2 to 3 am. Whether the investigation succeeds now hinges on the bravery of their leadership, including a Justice Minister, Public Prosecutor General, and Seoul District Prosecutors' Office chief who are either former secretaries or university alumni of the president. They need to be ready to put their position on the line, as the US Attorney General did when he resigned in protest of Nixon’s dismissal of the special prosecutor. At the very least, there should not be any attempts to halt or hamper the investigation.

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong? [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/8517133419684774.jpg) [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?![[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/6817133413968321.jpg) [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 4[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 5Why Israel isn’t hitting Iran with immediate retaliation

- 6S. Korea, Japan reaffirm commitment to strengthening trilateral ties with US

- 7Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 8[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 9Korea, Japan jointly vow response to FX volatility as currencies tumble

- 10‘Right direction’: After judgment day from voters, Yoon shrugs off calls for change