hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Chang Chun-ha’s family hopes to know truth of his death after 37 years

By Park Kyung-man, North Gyeonggi correspondent

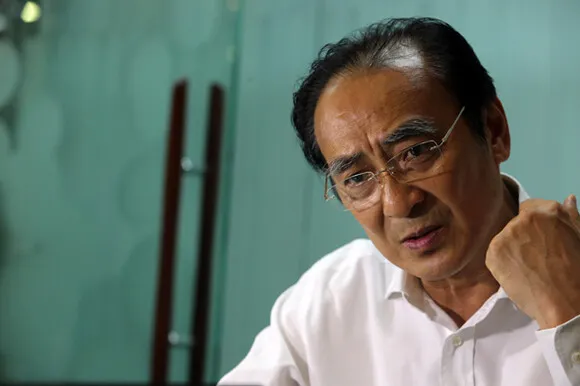

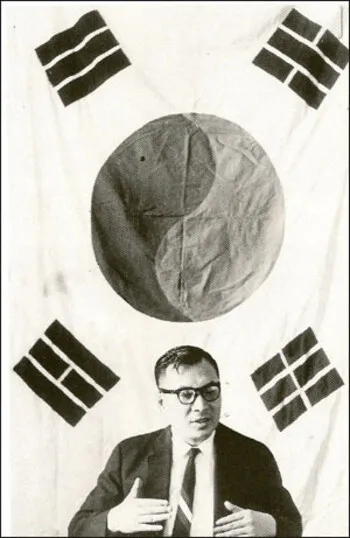

Chang Chun-ha was a fighter in Korea’s Liberation Army and a champion of democracy in post-independence South Korea. When his eldest son, Chang Ho-gwon, now 63, first saw his father’s crushed skull, he felt 37 years of rage suddenly roar up inside of him.

The older Chang had purportedly died in a fall while climbing Yaksabong peak in Pocheon, Gyeonggi province. The date was Aug. 17, 1975, a time when Park Chung-hee’s military government was reigning over the country. Yet the skull bore the telltale signs of a blow from a blunt instrument. Evidence at last, it seemed, to support all the claims over the years about foul play.

His father had been a man of great integrity, someone who always put the country and Korean people’s future ahead of himself. In front of others, the son treated him like a public figure, calling him “Mr. Chang.” When he finally bore witness to evidence of his father’s slaying while relocating his remains on Aug. 1, that was when he called the man “father.” And in that moment, he resolved to learn the truth and find out who was responsible.

The younger Chang met with the Hankyoreh on the Independence Day holiday August 15. The fact that his father’s reburial coincided with an election year, he said, seemed “like destiny, like after 37 years of lying in the grave he wanted to show that it was time to set history straight.”

Chang stressed the need to learn the truth about his father’s death and find the person responsible. “Even if we can’t punish them, shouldn’t we at least document the hidden truth of history and make sure such a thing never happens again?” he asked.

‘This has all been scripted’- Chang appears to have been murderedHankyoreh: Do you believe your father was murdered?

Chang Ho-gwon: They said he fell off a cliff, but he didn’t have the bruises and damage a fall like that would cause. There was only a little bit of blood behind his right ear. There were bruises on both armpits, which might have been caused when someone dragged him. The moment I saw the body, I thought, ‘This has all been scripted.’ I brought three doctors in as mourners and watched the examination. They poked at the wound behind the ear with a matchstick and it went straight in. They touched it and said, “It looks like the skull’s caved in.” Even then, a lot of people were saying it couldn’t have been a fall. Accounts from people who claimed to have seen my father fall turned out to be lies. The only conclusion was that he was never at the scene of the supposed fall. Something happened to him somewhere else, and they moved the body there. To get where he was supposed to have fallen, you have to rappel down 100 meters. It makes no sense at all.

H: Why did you wait until now to talk about it?

C: In those days, all you had to do was ask questions about the death and they would run you through the wringer for “violating the Emergency Decrees.” That happened to the Dong-A Ilbo reporter who wrote about the case. A reporter with Japan’s Mainichi Daily News was deported for bringing in pictures of the body that had been developed in Japan. I was going around trying to find out the truth about my father’s death, and I got a warning from an intelligence agent who told me “Don’t do anything stupid.” Then I was terrorized by four thugs. My jaw got broken, and I had to spend three months in the hospital. I was terrified they might kill me, so I fled to Malaysia.

I came back after Park Chung-hee’s death, but then I was arrested again by the Chun Doo-hwan administration and tortured. So I left again, this time to Singapore. I spent 24 years like that, on the run overseas, before finally coming back in 2004. Even if I had questions, I couldn’t tell anyone. I had to keep quiet about it.

H: No one investigated after the Kim Young-sam administration, either.

C: In 1993, the Democratic Party formed an investigation panel, but there were a lot of constraints on what it could do. All the establishment forces were working in politics, in the universities, the media, the legal world, and the investigation agencies. The barriers they put up were too high to clear.

And when they set up the Presidential Truth Commission on Suspicious Deaths (2000-2004) under Kim Dae-jung, I thought, “Unless the President puts his life on the line, these victims are going to end up being killed all over again.” The investigators had no authority to investigate, no power to compel these state organizations to hand over their information. There was one young prosecutor who said, “Maybe if we did it Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan’s way [i.e., torture], we’d get it, but if they keep their mouths shut, we can’t force them to do anything.”

I had high hopes for the Roh Moo-hyun government, since there weren’t any ties with the administration, but they were unprepared, and I ended up being disappointed.

“For 37 years, I called my father ‘Mr. Chang’”

H: What kind of person was your father?

C: A lot of the national leaders who fought Japan in the independence movement didn’t play any political role in the period after independence. But Mr. Chang did that under Rhee Syngman, and he did that through the 1970s, when Park Chung-hee’s Yushin dictatorship was at its peak. He was truly one of a kind, with great foresight and integrity. Even the opposition tried to rein him in. It was a situation where people were often being used politically and then left out in the cold. But he never lost the belief that he needed to do his part in bringing down the dictatorship. My father wasn’t just a politician. He was a leader of the people.

H: I’ve heard that your family suffered a lot.

C: The Yushin regime wasn’t like the Joseon era, when they retaliated against the family’s three generations, but they did turn you into beggars. You were as good as dead. Everyone went off to earn what they could to survive. To this day, we’ve never had a reunion. Our family didn’t have enough food, so a friend of my father’s snuck me a bag of rice, and ended up being dragged off by the Korean Central Intelligence Agency and having the living daylights scared out of him. When other politicians were attacked, it pretty much began and ended as political repression. I don’t think there are any other cases like ours where a family was broken apart completely.

I tried to get a job, but every time the intelligence agencies applied pressure to prevent it. I was 27, in the prime of my life. I went to a company where they knew my father and asked them to give me a job. The chairman just handed me an envelope and said, “I’m sorry.” I handed back the envelope and left.

My family members have gone their whole lives never owning a house. Right now, I’m living with my mother [88-year-old Kim Hee-sook] in Irwon [a neighborhood in Seoul‘s Gangnam district]. I paid a deposit of 10 million won (US$8,840) and monthly rent of 200,000 won (US$177), and get by on a monthly pension of 600,000 won (US$530). I’m not ashamed of being poor. I just think there shouldn’t be any more families that suffer like ours.

Park Geun-hye needs to reveal the truth before conciliationH: Do you have any desire to reconcile with Park Geun-hye [the New Frontier Party presidential hopeful and daughter of Park Chung-hee]?

C: I have no compulsion to meet Park Geun-hye. I could forgive the past and reconcile, but I can’t meet her as long as things remain unresolved. When I accepted her apology during the 2007 presidential election, I was doing a favor to a democracy movement colleague who was in an important position in the Grand National Party. She said she wanted to apologize for the past, and my mother accepted that. What Park Geun-hye said was, “I feel sorry about the people who lost their lives in my father’s time,” and my mother said, “Why don’t you act authentically instead of putting on a show?” That was the end of it.

H: What are your thoughts on her presidential bid?

C: We’re not enemies, me and Park Geun-hye. That was the family she was born into and the life she lived. It was her fate to be born Park Chung-hee’s daughter. But she shouldn’t concern herself with political power. Her father’s time was enough. She had everything, and I wish she would spend her time now serving the country and the people. Otherwise, we’re going to be on two different tracks.

If she does want to be in politics, then she needs to be her own woman, drawing a clear distinction with everything Park Chung-hee the dictator -- as opposed to “her father” -- did, and those establishment forces. Any reconciliation needs to come after the truth has come out. If you say, “let’s bury the hatchet” when you’re covering up a crime, then you’re concealing yourself. I don’t know that Park Geun-hye herself is a Japanese collaborator, but I am worried that those holdovers who enjoyed power in her father’s era will cling to her and hand the country over to Japan again.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Imperial tyranny, Korean humiliation [Column] Imperial tyranny, Korean humiliation](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2025/0912/7617576652278449.jpg) [Column] Imperial tyranny, Korean humiliation

[Column] Imperial tyranny, Korean humiliation![[Correspondent’s column] Cognitive dissonance in MAGA world [Correspondent’s column] Cognitive dissonance in MAGA world](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2025/0912/3417576648512186.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] Cognitive dissonance in MAGA world

[Correspondent’s column] Cognitive dissonance in MAGA world- [Editorial] Korea, US need a ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ on what job creation entails

- [Column] Why MAGA has its eyes set on Korea

- [Column] Lee still has his work cut out for him after summit with Trump

- [Editorial] Is this any way for the US to treat an ally?

- [Column] Lee’s difficult task of striking a balance on Japan

- [Editorial] Multipolar era means Seoul must broaden its diplomacy

- [Column] North and South Korea are no longer pawns in US-China-Russia relations

- [Column] Who we fail when we oversimplify the ‘comfort women’ issue

Most viewed articles

- 1Seoul says US must fix its visa system if it wants Korea’s investments

- 2North Korea said to have exposed numerous US spies after botched 2019 SEAL mission

- 3[Column] Imperial tyranny, Korean humiliation

- 4Freed workers arrive in Korea, one week after ICE raid in Georgia

- 5Korea’s president says firms will be ‘very hesitant’ about investing in US after ICE raid

- 6[Correspondent’s column] Cognitive dissonance in MAGA world

- 7Son of ex-President Roh Tae-woo tapped to serve as ambassador to China

- 8MAGA’s traveling circus comes to Korea

- 9[Column] Why MAGA has its eyes set on Korea

- 10Lee says he won’t sign any tariff deal with US that doesn’t benefit Korea