hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special series- part VI] Sexual minority students send letters to the schools where they suffered

By Um Ji-won, staff reporter

A was somewhat different from the other boys at his middle school in the Dongjak district of Seoul. Rather than running around on the playground like the other boys, A liked to cross-stitch or read books in the library.

The 50-year-old English teacher would call the boy “sissy.” “Hey sissy, you’re filthy,” the teacher would say. “If you touch me, my skin will rot.”

The other children giggled and repeated what the teacher said. A spent his three years of middle school in fear.

For teenagers who are coming to terms with their sexual identity, school is no shelter. The students are like prey, quivering with fear, and the school is a hunting ground.

In particular, the attitudes of teachers have a powerful influence in the sense that they become the model for how their peers view them.

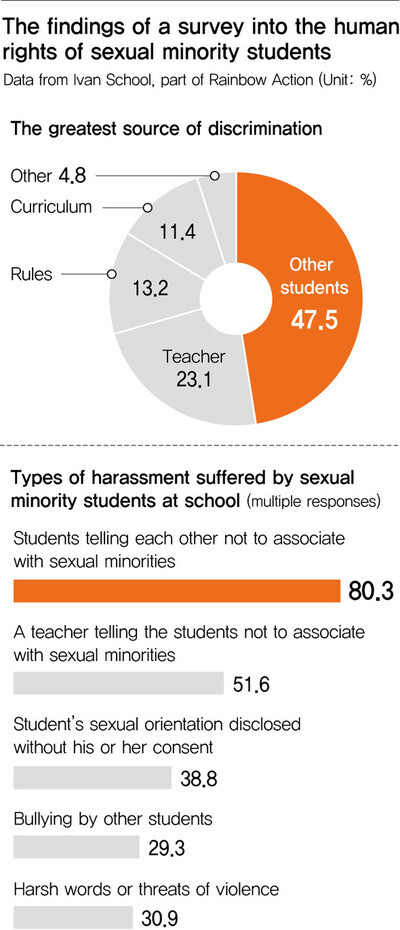

At the beginning of this year, the Ivan School, a group that is part of the Coalition for Human Rights of Sexual Minorities (known as Rainbow Action) that researches the human rights of LGBT young people, released the results of a fact-finding study on the human rights of sexual minority students in Seoul. According to the study, 23.1% of the 255 respondents named their school as the place where they feel the most discriminated against.

These sexual minorities have taken written letters in an effort to change schools. In these letters they candidly shared their experiences and appealed for change. The letters were then sent to the ones who had driven them to despair: their teachers at their alma maters.

On July 21, Ivan School announced that it had carried out a “letters to my school” project.

The project, which began on June 1 and lasted about a month, involved collecting letters written by sexual minority students to the teachers and current students at the schools from which they had graduated. These letters were then distributed to every high school in Seoul.

The “letters to my schools” project was designed as a way to transform schools by Stonewall, a UK organization dedicated to defending the rights of sexual minorities. When the project was first carried out, it had a positive impact.

Deep emotional scars are evident in the letters.

“‘You know gays get kicked out of schools, don’t you? Why do you have to be so dirty?’ the teacher said with a laugh. I don’t know why you think I’m dirty, or even why you force me to hide it.”

This is an excerpt from a letter that a high school student coming out of the closet sent to the teachers at the school the student is currently attending.

“One older student who came out as gay was ostracized by his friends when a teacher said that we shouldn’t associate with a guy like that,” the student wrote. “In the end, he dropped out of school.”

When what they really need is honest counseling about their identity, sexual minorities are only hurt even worse by the ignorance of their teachers.

“After I made my sexual identity known at the school, the therapist who was counseling me told me that I had gotten AIDS and sent me to a house of prayer,” admitted a girl who had graduated from a high school in Gwangju.

In fact, the girl did not have AIDS or any other disease. All she had done was like other girls.

“Sexual minorities are not suffering from some psychological condition,” the sixty sexual minority students who sent the letters said in a statement. “If the schools find it difficult to endorse homosexuality, it would be appreciated if they could at least not educate students from a distorted perspective.”

Ivan School mailed about 13,000 copies of the letters to teachers at public and private schools in Seoul on July 9.

They also sent rainbow stickers saying “I support sexual minority students” and promotional booklets containing guidelines for sexual minority students.

“It has been two years since the Seoul ordinance for the rights of students took effect, but we have yet to see any real change in the schools,” said Oh-Kim Hyun-ju, an activist with Rainbow Action.

“It is the teacher’s attitude that is the most important force in creating change. We are looking forward to seeing the teachers read the letter and volunteer to institute changes,” Oh-Kim said.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong? [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/8517133419684774.jpg) [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?![[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/6817133413968321.jpg) [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 4S. Korea, Japan reaffirm commitment to strengthening trilateral ties with US

- 5[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 6Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 7Why Israel isn’t hitting Iran with immediate retaliation

- 8[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 9[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- 10[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters