hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special series part II] Emotional laborers suffer while the customer is always right

By Nam Eun-joo, staff reporter

“The customer is always right.”

This is the slogan of a customer service center at a large corporation. It is also the phrase that defines emotional labor.

Naturally, treating the customer with courtesy is the essence of the service industry. But the way that companies enforce this courtesy through ruthless competition and regular humiliation is a different matter altogether.

Emotional laborers are unaccustomed to revealing the heartache and shame that they suffer day in and day out at the workplace. When they do start to share their stories, a shadow covers their faces, and their voices tremble.

The hundred or so workers at a call center for a certain logistics company are assessed each year for their level of courtesy by the Korea Management Association (KMA).

Jeong Yeon-hee, 27, is now in her fourth year of working at the call center. She says she is always rated as one of the top 10 employees. “But still, it’s hard to be friendly even when you want to be friendly,” Jeong said. “You’re always walking a tightrope between courtesy and efficiency.”

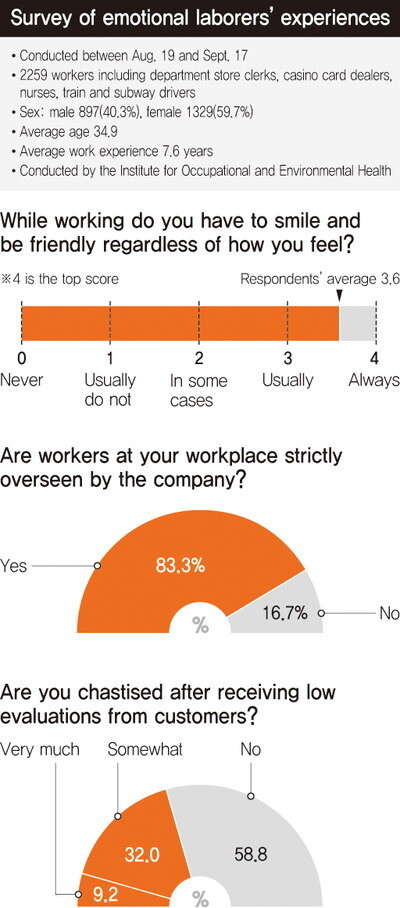

[%%IMAGE2%%]Every moment, the quality of employees’ performances is being quantified. This company complies with the Labor Standards Act. It gives its employees one hour of break time and has them work an average of nine hours a day, giving them an hour of total time each day to process calls after customers hang up.

But when customers use more than 30 minutes of their processing time, a red light blinks on at their seat. This is a warning light telling them that their work performance is in danger.

“The only way to get a strong performance review is to use as little of your processing time as possible,” Jeong said. “Time spent using the bathroom is measured, too, so we have to just sit and hold it. You know what we’re most afraid of hearing from customers? When they ask us to check on something and call them back. Time spent calling a customer is subtracted from our processing time.”

When assessing its employees, the company takes into account how much processing time they use, how courteous they are to customers, and how impressive their sales figures are.

Employees that get low scores for several months in a row steel themselves for a pink slip.

“I can feel something piling up inside. One doctor told me I was depressed, and another said I had trouble with a disc. They just keep prescribing me drugs,” Jeong said. “Yesterday, I got very close to getting in a fight with a customer. I just don’t know what to do with myself anymore.”

Kim Gwang-su, 38, has been working as a repair technician for a Samsung Electronics service center in Ulsan for the past 10 years. Starting two years ago, he felt pressure in his chest and shortness of breath whenever he was about to enter a customer’s house. One time, he even fainted for 10 minutes. Since then, he has been getting medical treatment.

After a number of tests, a psychiatrist diagnosed Kim with having panic disorder, a condition characterized by periodic panic attacks.

“Even when the product is defective to begin with, if the customer makes a complaint, the repair technician gets reprimanded and has to write a letter of apology. I haven’t been able to speak my mind to customers for so long that I think I might explode. I’m afraid of the customers.”

Happy Call has produced a system whereby repair technicians are unable to dispute the demands of unreasonable customers.

“I got a call from a customer who said that the robotic vacuum cleaner had sucked up some dog poop and wanted me to clean it,” one technician said. “When I asked my supervisor if I really had to go, he said of course I did and asked me why I would want to screw up the team’s performance record.”

So the technician cleaned the dog poop and didn’t even get paid for it.

In several recordings sent to the Hankyoreh by the labor union for Samsung Electronics service centers, customers can be heard using foul language, grabbing technicians by the collar, pushing them into their car and driving them around, and threatening them.

There are some horrible people out there, and technicians are bound to run into them at some point. The problem is that, even in situations like this, technicians do not have the right to defend themselves or to escape the situation.

“No matter what kind of violence technicians suffer, they can never bring a case against a customer. The supervisor is always in the way,” said Wi Yeong-il, chief of the Samsung Electronics Service chapter of the Korean Metal Workers’ Union.

Psychologists say that humiliation leaves lasting scars that can never be completely healed. Employees who are working at the same center at Kim show symptoms of panic disorder just like Kim.

The duty-free shop in a major hotel in downtown Seoul holds a customer service training session during every morning meeting. Kim Seung-hee, 31, who is on the sales staff there, describes the scene. “One time the manager told us that a customer told her to get down on her knees and beg, so she did so. Shee said that the customer helped her get to her feet and asked if she had done something wrong,” Kim said.

“She doesn’t think it’s a big deal to tell us stories like that. The employees don’t show it, but it pisses us all off. Basically, she’s telling us we should do the same thing. Do we really have to go that far?”

“The managers tell employees to do whatever it takes to keep customers from visiting the complaint department,” said Park Won-woo, head of the Samsung Everland branch of the labor union. “That means employees have to beg for mercy even when the customer’s complaint is really unfair. It’s quite common for employees to get on their knees and beg.”

What happens to emotional laborers when they have to get on their knees and beg to avoid an unpleasant situation?

“Humiliation tears down and destroys one’s humanity worse than any kind of violence,” said Jeong Hye-shin, an expert in psychological healing.

“When people are stripped of their dignity, they start feeling suicidal urges and a sense of complete helplessness. When a company forces its employees to feel humiliation as a regular part of their workload, they experience wild mood swings from helplessness to uncontrollable rage. Eventually, people can experience a breakdown.”

“There is no country where workers in the service industry are viewed in terms of a master-servant relationship as they are in Korea,” said Lim Sang-hyeok, director of the Wonjin Institute for Occupational and Environmental Health (WIOEH) at Green Hospital.

“The depression and panic disorder experienced by people doing emotional labor all result from the same thing. This is not a sustainable kind of work.”

Is there anything she wanted to tell the customers who were disrespectful to her and cursed at her? “I don’t have anything to say, and even if I did, they wouldn’t understand. But I do want to give them a rating the way they do with us. I wish I could rank customers on a scale of 1 to 100,” Jeong said.

There was a recording of a phone conversation that became quite popular online this summer. A customer service representative is telling an elderly woman she has reached LG Uplus, but the woman, who is hard of hearing, thinks he is saying that there is a fire. This exchange takes place multiple times, with the service representative patiently repeating the same lines.

People who listened to the clip thought it was hilarious, and the employee was regarded as a paragon of courtesy. But where exactly does that patience come from?

The names of sources in this article have been changed to protect their privacy.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 4[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 7[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 8Constitutional Court rules to disband left-wing Unified Progressive Party

- 9Nearly 1 in 5 N. Korean defectors say they regret coming to S. Korea

- 10‘Right direction’: After judgment day from voters, Yoon shrugs off calls for change