hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special report] The truth of Cyber Command’s political interference

By Ha Eo-young and Jung Hwan-bong, staff reporters

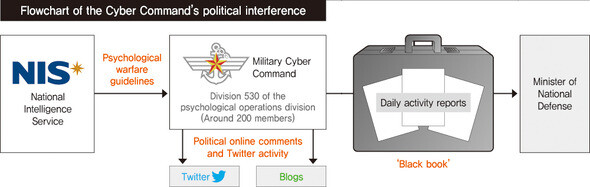

The Ministry of National Defense has been arguing that the politically slanted online messages and Tweets by agents in the military’s Cyber Command are nothing more than the agents’ “personal deviations.” The claim is that these activities were not connected to similar messages by National Intelligence Service (NIS) or part of any organized military activity, and that the military command was unaware of them.

But current and former senior military officers have made very specific and concrete claims that the Cyber Command did conduct a psychological operations campaign on NIS orders, with daily reports on the results provided to the military leadership.

Some of the officers making the claims have experience working under the Cyber Command. If the allegations are true, it would mean that the denials to date from the ministry and NIS are false, and that the NIS did in fact orchestrate and control political online and Twitter activities by agents in the Cyber Command‘s division 530.

■ NIS directives in the name of ‘cooperation’

The current and former military officers said NIS directions to the Cyber Command did not come in official document form. The methods used were designed not to leave a trail, including verbal commands and demands for video distribution that would not be identifiable as part of an operation. When orders were given on paper, they were often couched under the title “operational coordination.” So-called “atypical psychological operations directives” - with a different format from internal military drafts - were delivered to the director and key officers with the division 530, the Cyber Command’s psychological operations division.

“At first glance, what the NIS sent might seem like it was just a simple request for operational coordination,” said a military officer in the Ministry of National Defense who spoke on condition of anonymity. “But if you take into account that the entire Cyber Command operation was based on it, it really was an operational plan, a set of guidelines.”

Once the orders were given, teams of four to five agents in the division were reportedly assigned specific duties. According to guidelines, agents on each team would go on to wage an online opinion campaign for the next 24 hours straight, until a meeting held by the commander the following day.

The agents saw themselves as “troops on the cyber-battleground,” executing an operation on orders from above. But their actual activities were focused more on supporting the conservative ruling Saenuri Party (NFP) and its candidate Park Geun-hye, and knocking down opponents and candidates in opposing parties. The campaign was a clear-cut political crime, with state money and manpower committed to illegally manipulating popular opinion and damaging the opposition.

Kim Min-seok, a spokesperson for the ministry, said there was “nothing like any NIS guidelines as far as I am aware. My understanding is that the structure does not allow the NIS to give directions.”

■ ‘Black book’ reports of daily activities

The Cyber Command delivered daily reports to the minister in the form of so-called “black books” titled “project reports,” sources said.

“Every morning, the leaders of division 510 [cyber protection and control] and division 530 [psychological warfare] would meet at the command conference room, where the division 510 operates, and examine the Cyber Command report that would be sent to the minister,” said a ministry source familiar with the Cyber Command on condition of anonymity. “But details about psychological warfare operations were discussed in private between the commander and the division 530 leader after the division 510 leader had left the room. The Cyber Command would look at the previous day’s operation results and examine the special ‘cooperation orders’ from the NIS.”

The division 530 activities would end up in a report for a specific project. The content consisted mainly of reports on the previous day’s operations, current or scheduled projects, and special notes.

“The ‘current and scheduled projects’ section contained that day’s new orders [from the NIS], while the special notes included records of things like videos and posters sent down by the NIS as part of a policy focused on public relations,” a military officer said on condition of anonymity. “The name ‘NIS’ almost never appeared in the report. If you look at it, you’d think it was a typical project report.”

The approach of classifying the results of online psychological operations and reporting them directly to the top officer started back in 2010, before the Cyber Command was launched. At the time, the division in charge of online psychological warfare operations were under the operational headquarters for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, with the division director reporting the results directly to the chief of operational headquarters and the Joints Chiefs of Staff chairman. “Black books” were also used, the contents of which were top secret.

Kim Min-seok said the black books served a different purpose. “They contained information about online trends, not the results of projects,” he said. “And they weren’t just reported to the minister. They were also circulated to the necessary departments for reference in their duties.”

■ Quantifying the online performance of every agent

Division 530 had around ten teams, each with four to five members. They were classified into two sections, domestic and international. While most of the division’s members were military officers and civilian employees with experience in psychological operations, the international section was also assisted by around a dozen foreign language specialist soldiers who were in charge of translation.

The three main categories of agent duties were “aiding the Commander-in-Chief [the president],” “promoting defense policies and countering slander,” and “promoting government policies and countering slander.” Psychological operations “themes” for the day according to NIS directives were reportedly classified into one of these categories.

Online posts publicizing the current president might be classified as “aiding the commander-in-chief,” while publicity for a state undertakings like the Four Major Rivers Project would be listed as “promoting government policies and countering slander.” Once assigned their duties, agents would go to work on public opinion via online message boards, portal sites, and social media.

Activities on certain sites and media were quantified for the reports. Agents would “work” message boards and social media where criticisms of the president’s remarks or government policy were common, and then draw up numbers and graphs on the increase in more positive posts. Reports on “countering slander” gave percentages for the “reduction in unfavorable content” and “increase in favorable content.” Daily changes in overall favorability were listed with graphs as daily results for the next day’s report. Numbers and diagrams were drawn up for the results of all activities associated with online psychological operations.

Kim Min-seok offered a different explanation for the reports’ content. “The reports contained analyses of online and offline media trends,” he said. “Reports were given each morning to the minister and key officers on the black books for intelligence divisions with ‘Special Intelligence’ content and for the Cyber Command. They were designed as references for policy, with information about online trends both domestically and internationally, in places such as China.”

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 2After 2 years in office, Yoon’s promises of fairness, common sense ring hollow

- 360% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 4Yoon’s broken-compass diplomacy is steering Korea into serving US, Japanese interests

- 5[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

- 6S. Korean first lady likely to face questioning by prosecutors over Dior handbag scandal

- 7Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 8[News analysis] Jo Song-gil’s defection and its potential impact on inter-Korean relations

- 911 years after US decamped, military base in Busan still festering with pollution

- 10[Editorial] The ideals of the Korean Provisional Government are still threatened today