hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

“How are you?” student movement becomes nationwide phenomenon

By Song Ho-kyun, staff reporter, Jung Dae-ha and Jeon Jin-sik, Gwangju and South Chungcheong correspondents

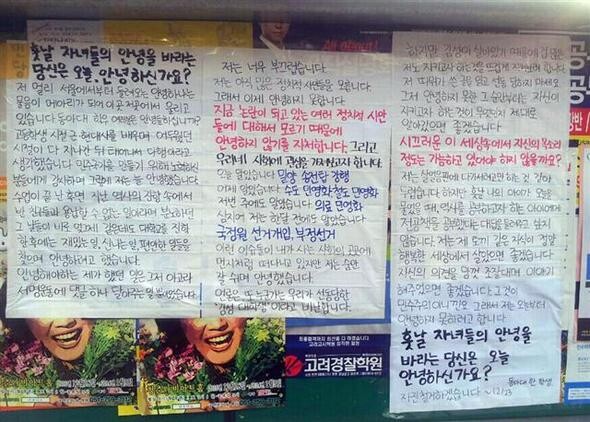

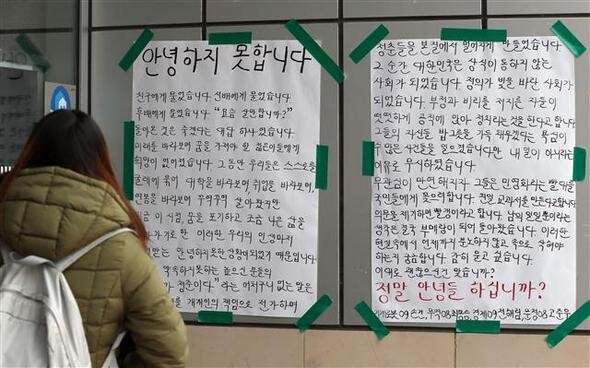

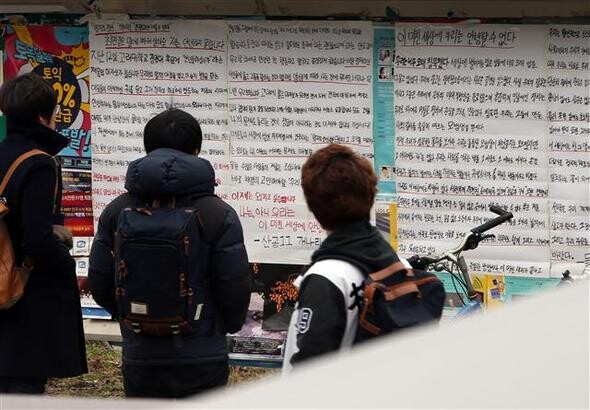

The “how are you nowadays?” series of large hand-written posters on university campuses have become a nationwide phenomenon spanning generational, regional, and class divides. Not only university students but also high school students, office workers and housewives have been writing similar posters expressing their own awareness of the issues.

“So many posters have been written in response that we haven’t been able to keep track of them,” said philosophy student Kang Tae-kyung, 25. Kang is running the official “how are you nowadays?” Facebook page along with Ju Hyun-u, 27, the business student who put up the first hand-written poster at Korea University.

The official Facebook page had more than 248,000 ‘likes’ as of the morning of Dec. 17.

The duo is also running the “Reply 1228” campaign [a parody of the popular “Reply 1997” and “Reply 1994” TV shows], which seeks to get 1228 people to submit photographs of their hand-written posters. In addition to universities in Seoul, KAIST in Daejeon also saw posters put up by around ten students.

The most noticeable development is the participation of high school students. The topics about which they are writing are diverse, including criticism of the political situation and educational issues.

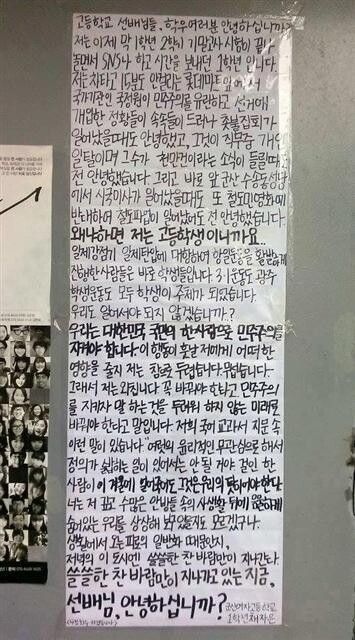

On Dec. 16, Chae Ja-eun, 16, a student at Gunsan Girl’s High School, put up a poster she had written on the wall of her school. “When evidence was presented that the National Intelligence Service had trampled on democracy by interfering in the election, and when candlelight rallies were held, I was okay. When the agency claimed that agents had acted on their own despite reports that tens of millions of comments had been posted, I was okay. Why? I’m a high school student. But students took the lead during the March 1st independence movement and the Gwangju student movement. Shouldn’t we take action, too?” Chae wrote in her poster.

Jeong Hyun-seok, 18, a student at Hyosung High School in Seongnam, Gyeonggi Province, wrote a poster of his own.

“Students don’t ask, so in the end the government doesn’t make any policies for students,” Jeong said. “At some point, we began taking it for granted that students keep committing suicide each year because of disappointment about their grades. That’s why I’m not okay.”

Citizens who have been reluctant to participate in political activity have also started writing posters. A worker at Dasan Call Center, the general hotline for the city of Seoul, wrote an unsigned poster.

“I thought that my coworkers who were taking part in labor activities were building castles in the sky. A female coworker shaved her head to change a 30,000 won (US$28.50) holiday gift certificate into 80,000 won in cash. But these people were getting things done, and I was being servile, and I was sorry. I’m not going to sit on the fence anymore. I’m going to join them, because I’m not okay.”

Another citizen wrote a poster that she signed as “your mother, class of 1982” and posted to the rear gate of the College of Politics and Economics at Korea University, where the “how are you nowadays?” phenomenon began.

“When I raised you, I am ashamed to say that I taught you to serve good grades and money. I’m sorry. Now I’m applauding you as you speak up,” the anonymous mother wrote.

Analysts are offering a variety of explanations for this phenomenon, including the disappearance of politics and distrust of the online space.

“Along with the uncommunicative and self-righteous administration of President Park Geun-hye, both the ruling and the opposition parties have failed to reflect the various needs of the Korean people in the institutionalized political process,” said Choi Chang-ryul, professor at Yong In University. “I believe that citizens have stepped forward to take voluntarily collective action because they had no one to represent them.”

“When you post something online, the reactions can range from criticism to cursing depending on your political persuasion,” said political commentator Kim Min-ha. “The National Intelligence Service comment case was particularly decisive. Since citizens sense that the online space by itself is no longer enough, they are once again attempting the analogue method of communication through these hand-written posters.”

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing? [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0705/2917201664129137.jpg) [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?![[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0703/8717199957128458.jpg) [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor

[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor- [Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy

- [Editorial] Korea needs to adjust diplomatic course in preparation for a Trump comeback

- [Editorial] Silence won’t save Yoon

- [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

- [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war

- [Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

Most viewed articles

- 110 days of torture: Korean mental patient’s restraints only removed after death

- 2Real-life heroes of “A Taxi Driver” pass away without having reunited

- 3Koreans are getting taller, but half of Korean men are now considered obese

- 4Former bodyguard’s dark tale of marriage to Samsung royalty

- 5Can the IPEF deliver the US dream of an Asian economy without China?

- 6Chip powerhouse S. Korea struggles to strike balance between China’s demands, US pressure

- 7Around 2 mil. Koreans conscripted to labor from 1939 to 1945

- 8On South Pacific island, Korean fishermen again looking to buy sex

- 9National security advisor’s ouster could afford hard-liner Kim Tae-hyo stronger influence

- 10[Column] “Hoesik” as ritual of hierarchical obedience