hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Huge increase in university students deferring graduation

By Jeon Jeong-yun and Kim Ji-hoon, staff reporters

As of early 2014, she had enough credits to graduate from Yonsei University, but chose not to. Instead, the student, surnamed Jeong, chose to defer her graduation. It was a last, desperate grasp after repeatedly coming up short in qualification examinations and job applications.

“I was afraid the human resources staff at the companies would look askance at that blank period on my resume,” Jeong said. “I’m not a part of society right now, and it really seemed like I’d be pushed to the edge if I graduated. I just couldn’t do it.”

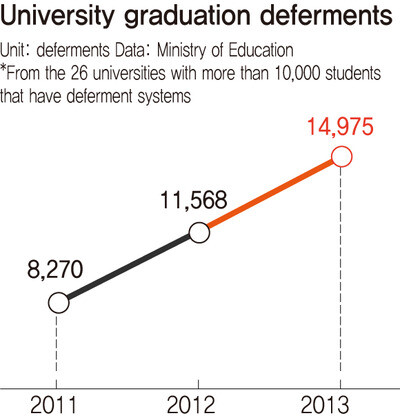

In an age of high youth unemployment, cases of graduation deferment, where students choose to remain in school even after qualifying for graduation, have nearly doubled in the past two years. Figures provided to the office of New Politics Alliance for Democracy lawmaker An Min-suk on Apr. 3 by the Ministry of Education show the number of applicants at the 26 universities with more than 10,000 students that had deferment systems before 2011 rose from 8,270 that year to 14,975 in 2013 - an 81% increase. In 2014, a total of 12,169 students had already applied as of March. Once second semester numbers are factored in, the total could be far greater than last year’s. So far this year, 15,239 students at 33 universities - including the ones that first introduced the system - have deferred graduation.

The ministry figures mark the first-ever statistical tallying of deferments at the national level. The graduation deferment system allows students who meet their graduation requirements to retain their enrollment status with the school’s consent. Because the universities implement it on their own, no ministry statistics existed before this year.

The system was first introduced in the late 1990s to manage the number of unemployed graduates in the wake of the foreign exchange crisis and International Monetary Fund bailout. Now the numbers are pointing to an explosion in recent years.

In general, the students are postponing graduation for the same reasons as Jeong. A survey of 1,100 job-seeking graduates or near-graduates by the website Job Korea found the most common reason to be “building a stronger resume,” given by 50.8%. Another 16.1% cited “vague misgivings,” 45.3% mentioned “companies not hiring graduates,” 25.4% pointed to “a preference for prospective graduates when choosing interns,” 15.5% wanted to “build job-related experience,” 12.6% mentioned “the chance to take part in a school employment support program,” and 9.6% cited “use of the school library and other facilities.”

While the lack of employment weighs on the students, they are now having to carry an additional burden from the universities’ own cold calculations. Twenty-four of the 33 universities with graduation deferment systems, or about 73%, charge extra for the privilege. Twelve of them charged anywhere from 100,000 to 270,000 won (US$95-255) even for students not attending classes. The other twelve require all students to attend classes even if they have met their graduation requirements. An’s office estimated that the schools charge between 300,000 and 700,000 won (US$284-662) per subject.

Yonsei is one of the schools that requires deferring students to attend classes. An employee in the university administration office said students had to pay “a minimum of around 500,000 won,” or US$473, although the number varies by major.

In 2013, a total of 3,141 Yonsei students deferred graduation, which means that even at the lowest rate, they would have paid a total of more than 1.5 billion won (US$1.4 million) in tuition.

To put off graduating, Jeong paid 600,000 won (US$567) to take a general education course. Since her own finances are so tight, she turned to her older sister, a company worker, for the money. The class itself means little to her.

“It’s just an extra class in my last semester,” she said. “Who has time to really focus on a class when they’re preparing to get a job?”

Adding to the burden on unemployed young people is the fact that they are ineligible to apply for student loans or scholarship to cover their deferment tuition. A University of Suwon student with the surname Ahn turned to his parents for the 500,000 won to cover the “ninth semester” when the student loan option was ruled out. But an internship that became available after the deferment means Ahn is now unable to attend. The school said it would count the internship toward attendance - but didn’t refund Ahn’s tuitition.

“We can’t simply allow these students - people who are putting off graduation at the threshold of a harsh job market - to have their hearts broken all over again,” said An Min-suk. “The Ministry of Education needs to look into these university deferment costs and come up with improvement measures.”

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0415/7517131654952438.jpg) [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics![[Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0412/1017129080945463.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

[Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

- [Guest essay] At only 26, I’ve seen 4 wars in my home of Gaza

- [Column] Syngman Rhee’s bloody legacy in Jeju

- [Editorial] Yoon addresses nation, but not problems that plague it

- [Column] Can Yoon and Han stomach humble pie?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 2[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test

- 3[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- 4[Photo] Cho Kuk and company march on prosecutors’ office for probe into first lady

- 5[Column] A third war mustn’t be allowed

- 6‘National emergency’: Why Korean voters handed 192 seats to opposition parties

- 7Exchange rate, oil prices, inflation: Can Korea overcome an economic triple whammy?

- 8After Iran’s attack, can the US stop Israel from starting a regional war?

- 9[Editorial] New KBS chief is racing to deliver Yoon a pro-administration network

- 10[Editorial] S. Korea should take a note from US-China tactical compromise