hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special report] Korea is dangerous for kids, especially the poor

By Im In-tack, staff reporter

In South Korea, children’s lives are dangerous, particularly in the cases of children from poor households.

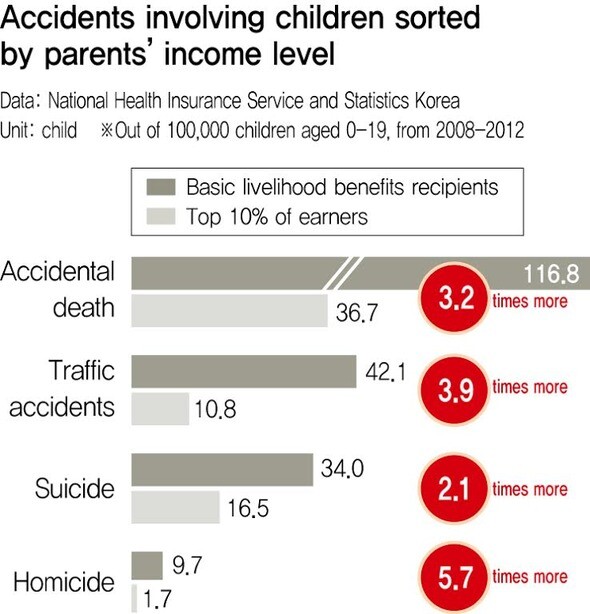

A study on the socio-economic backgrounds of victims who suffered fatal accidents has found that children and teenagers from underprivileged households are up to 3.2 times more likely to die as a result of exposure to safety hazards in their day to day lives. Over a period of five years from 2008-2013, the study analyzed data related to young people from infancy to 19 years of age.

Out of every 100,000 children and young adults who are eligible to receive basic livelihood benefits, 117 died in fatal accidents. Among children from households of the top ten percent of earners, the number was 37 out of every 100,000.

The Hankyoreh reported in May that regardless of the socio-economic status of parents, the proportion of fatal accidents among minors in South Korea was the highest amongst OECD countries. This latest report shows that underprivileged children are disproportionately exposed to risks of dangerous and sometimes fatal accidents. The Hankyoreh analyzed statistics of National Health Insurance subscribers and fatalities tallied by Statistics Korea, acquired through the office of New Politics Alliance for Democracy (NPAD) lawmaker Kim Yong-ik, a member of the National Assembly Health and Welfare Committee.

The influence of socio-economic status on health and safety is widely acknowledged in academia. But, this is the first analysis that encompasses all national health insurance subscribers to study the relation between parents’ income and fatal accidents among children. It is also the first to analyze the disparity in mortality among minors between low and high income households.

The study illustrates that minors’ fundamental rights, which the state or government are responsible for, affected by socio-economic status.

The rate of accidental deaths among minors in South Korea has been declining slightly since 2009, but slower than in other developed countries. Worse still, the disproportionate rate of accidental deaths in relation to income, has intensified.

The five-year study shows that for every 100,000 children and teenagers in the lowest decile, there were 22.3 deaths in 2008, 24.7 deaths in 2009, 22.5 in 2010, 23.8 in 2011, 24.1 in 2012 - showing that the numbers have stayed the same or improved slightly for minors in this socio-economic category.

On the other hand, children of families of the top decile are less likely to face a fatal accident. In 2008 out of 100,000 children and teenagers, there were 7.2 deaths, 8.2 in 2009, 7.0 in 2010, 7.9 in 2011 and 6.2 in 2012 - showing a steady but downward trend.

A comparison of the two groups shows that in 2008, there were 15.1 more children from poor families who were victims of fatal accidents than children from the top income decile. In 2009, the difference stood at 16.3, then 15.5 in 2010, 15.9 in 2011 and 17.9 in 2012.

By definition, accidents can happen to anyone - rich or poor. However, failing to understand the disparity in mortality makes it difficult to protect the right to life and development of children and teenagers in South Korea.

The Hankyoreh has found that children from lower income households have a higher chance of falling through the social safety net. Children of families basic livelihood benefits are 3.9 times more likely to die in a car accident (statistics calculated over a five-year period), 2.1 times more likely to die from suicide, 5.7 times from homicide, 5 times more from drowning and 3.5 times more from falling to death.

Kim Dong-Jin, a Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) deputy researcher, said, “Income defines one’s social community and the physical environment where he or she lives.” Kim added that the main reasons for the disparity in accidental death lie in the “probability of facing accidents caused by negligence” and the “access one has to the appropriate means of dealing with the accident”. For example, traffic accidents are the biggest cause of accidental deaths. Not only do regions with a larger proportion of disadvantaged families have less safety measures and lack safety awareness, but it also takes longer for emergency services to reach certain neighborhoods.

This is linked to regional and urban-rural disparities. Despite being registered as ‘special protection’ zones, North Gyeongsang Province and Gangwon Province recorded the highest number of school bus accidents (statistics from both Provincial Offices of Education, as of August). June Kyung-ja, a Soonchunhyang University professor of nursing and child poverty specialist, said, “In rural areas, adults no longer look after the neighbors’ children while the other parents are working. Children in rural areas are being forgotten, at that puts them at risk. On the other hand, city kids climb into hakwon [after school institute] buses that drive them to their next activities until eventually dropping them off at home. Kids in the countryside are often left to occupy themselves.”

The prevalence of disease is lower in children than in adults. But the government also needs to come up with comprehensive measures to prevent accidents where the direct or indirect perpetrators are adults.

Kim Myung-hee MD, a researcher at the People’s Health Institute, said, “Social and environmental inequalities affect children more than adults. Children face more inequalities in regard to access to healthcare, which is a real problem that we should address and take responsibility for as a society.”

The social cost of waiting until these children become adults to solve this problem will be a far greater burden. A 2007 World Health Organization report said “every dollar spent on a preschool child will save 17 dollars a year for the next 40 years of his or her life.”

Experts demand functional solutions as well as socio-cultural measures in order to improve the situation.

"We make it a primary healthcare goal to find and assist children and teenagers who are victims of domestic abuse as early as possible,” said Ewha Womans University medical school professor Jungchoi Kyung-hee. Reinforcing speed limit regulations (according to Kang Young-ho, Professor of Medicine at Seoul National University) is seen as one of the institutional strategies aimed at helping more children from lower income families.

June Kyung-ja goes further to say that “There is a pressing need to have a discussion about the labor conditions and low wages that leave children living in empty homes, because their parents are underpaid and overworked.”

Advisor and former director of Health Right Network Cho Kyung-ae says “We need to make efforts to develop our own capability to keep our children safe.” Perhaps it is time to revitalize community efforts to protect minors.

There are many different ideas for mid and long-term plans, but many experts point to the example of Sweden. The government set up six broad goals to improve healthcare: 1. Intensify social solidarity 2. Provide every child with a safe and fair environment 3. Focus on improving labor conditions etc. In Sweden these targets were introduced 14 years ago, at the turn of the millennium.

NPAD lawmaker Kim Yong-ik said, “This groundbreaking analysis from Hankyoreh provides us with important and surprising data”. Kim says he is “planning to demand medium and long-term policies to tackle the inequalities that children and teenagers encounter related to accidents” before the National Assembly Standing Committee.

For further information:

The rate of accidental deaths of children in relation to parents’ income over the past five years shows that:

In families who receive free medical benefits including basic livelihood, there are 117 deaths per 100,000 children (505 fatalities out of 432 412 people)

For families in the lowest earning 10%, there are 63 deaths per 100,000 children (402 out of 639 412 people)

For families in the second lowest earning decile, there are 60 deaths per 100,000 children (332 out of 555 878)

For families in the third lowest earning decile, there are 63 deaths per 100,000 children (360 out of 569 787)

For families in the fourth lowest earning decile, there are 64 deaths per 100,000 children (458 out of 706 173)

For families in the fifth lowest earning decile, there are 56 deaths per 100,000 children (463 out of 825 108)

For families in the sixth lowest earning decile, there are 57 deaths per 100,000 children (572 out of 1 002 800)

For families in the seventh lowest earning decile, there are 48 deaths per 100,000 children (582 out of 1 204 069)

For families in the third highest earning decile, there are 43 deaths per 100,000 children (632 out of 1 473 780)

For families in the second highest earning decile, there are 41 deaths per 100,000 children (728 out of 1 753 837)

In families of the top decile, there are 37 deaths per 100,000 children (623 out of 1 697 428)

As a reference, families of the fifth income decile earn between 1.7 million and 2 million Korean won (US$1682-$2015) according to 2012 statistics.

Translated by Lee Yena, Hankyoreh English intern

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 2Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 3Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 4[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 5Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 6[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 7Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 8New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10Korea ranks among 10 countries going backward on coal power, report shows