hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

KDI report: South Korea’s household debt resembles pre-crisis US

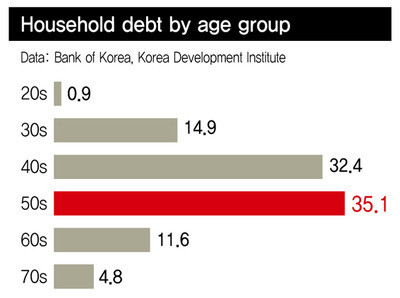

Fiftysomething baby boomers born between 1955 and 1963 have barely made a dent in the huge household debt they racked up amid a spike in real estate prices a decade ago. Now figures show them with the largest debt of any age group.

As the generation’s incomes dwindle, members are looking less and less likely to repay their debt - which experts fear risks becoming a time bomb for household debt when they retire ten years down the road. Meanwhile, the South Korean government has yet to take any steps to address the looming problem. If anything, its policies, such as its decision last August to drastically reduce regulations on real estate mortgages, stand only to further increase household debt.

Kim Ji-seop, a researcher at the Korea Development Institute (KDI), laid out the troubling situation in a Nov. 20 paper titled “Changes to the Age-Group Breakdown of Household Debt.”

“South Korea’s household debt last year is similar to the level in the US in 2004, four years before the subprime mortgage crisis, but its qualitative structure is worse,” Kim warned.

In 2004, the US had a household debt to GDP ratio of 86.3%; South Korea’s ratio for 2013 was a similar 80.7%. Trends have also been similar: US debt rose sharply around 2000, while South Korea’s began to spike in the early to mid-’00s. In other words, South Korea’s household debt today resembles the US ten years ago in its scale and patterns.

But a breakdown by age group showed a far greater portion of debt held by heads of households in their fifties in South Korea than in the US. In 2004, the percentage of total household debt for this segment in the US was 22%; for South Korea last year, it was 35%. While the two countries’ percentages of household debt out of GDP were roughly the same, South Korea’s was skewed more to a particular age range. Indeed, when heads of households in their forties are factored in, the percentage of debt rises to 55% for the US, but 67% for South Korea.

The debt-to-income ratio, a comparison of financial debt and annual earnings, was 149% for South Korean heads of households in their fifties - 43 percentage points higher than the 106% recorded by the US. The number means that South Korean fiftysomethings are shouldering more debt relative to their income than the same segment in the US in 2004. The ratio of debt to assets was also higher in South Korea at 19%, compared to 11% for the US. Not only are South Koreans in their fifties less equipped than their US counterparts to repay their debt, but they also have fewer assets such as real estate to provide funds to pay it back.

In the US, household debt continued growing after 2004, before dropping in 2008 with the subprime crisis. South Korea’s debt has also been steadily rising since 2008.

“Because a significant portion of the debts incurred in the mid-‘00s by the baby boom generation - then in their forties - were not paid back, the percentage of debt for people in their fifties was higher in 2013, when they were in that age group,” the report explains.

“It now appears very likely that South Korea’s household debt problem will deepen in ten to twenty years when these forty- to fiftysomething heads of households retire,” it warned.

While the debt remains the same, retirement is poised to cut into the income that allows holders to repay it.

“The household debt situation is serious for people in their fifties, but it‘s tough to find any measures from the administration to address it,” Kim told the Hankyoreh in a telephone interview.

Kim Yong-bum, Financial Services Commission’s financial policy bureau chief, was circumspect about predictions of a looming debt catastrophe.

“As far as household debt is concerned, we’re approaching and analyzing it from various perspectives,” he said.

“But we don’t seem to be at the stage yet where we should be too concerned about the household debt issue,” he added.

Kim went on to note that while the US allowed unrestricted loans even to low income earners in the ‘00s, South Korea has relatively stringent terms for its bank loans. The argument is that South Korea’s loans are basically better than the US‘s were, thanks to debt-to-income (DTI) ceilings and other regulations applied to banks from 2003 onward.

Authorities also pointed out that South Korea’s capital adequacy ratio, according to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), stood at 14.2% as of late September. The international minimum ratio is 8%; domestically, it is 10%. A high capital adequacy ratio means banks are more capable of absorbing losses: even if loans are not repaid, the risk of a bank collapse or “systemic risk” is relatively small.

But with Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Strategy and Finance Choi Kyung-hwan adopting looser household debt regulations since taking office in July, fears of a debt calamity are growing. Under the policies adopted by Choi’s team, financial authorities have loosed DTI and loan-to-value (LTV) restrictions on loans since Aug. 1. Between August and October, household debt has risen by four to five trillion won (US$3.6-4.5 billion) each month.

Financial authorities, who were emphasizing “qualitative improvements to the debt structure” as recently as last year, tightened their household debt management with first-ever qualitative oversight measures early this year, using DTI ratio as an indicator. Since Choi took office, those policies have been more or less abandoned - leading many to question whether the administration is committed to managing household debt at all.

Speaking at a parliamentary audit on Oct. 27, Choi said the policies were “aimed more at increasing household disposal income than at reducing total household debt.”

“Three months is too soon for these policies to show real effects,” Choi added at the time. “We’re going to take the time and do our best to make sure they keep producing steady results.”

Meanwhile, the annual rises in real wages, the core component of household income, has been dropping off steadily this year.

By Kim Kyung-rok, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 2Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 3[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 4New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 5Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 6Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 7[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 8Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 9N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 10Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?