hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Low-income folks’ only wish: that poverty isn’t passed down to the grandkids

It was early afternoon on Jan. 27, and Kim Hyun-sang (62, not his real name) was delivering 30 kilograms of scrap paper he had been collecting early morning to a junk shop near his home. He was paid 90 won (US$0.08) per kilogram, 2,700 won (US$2.50) in total. Had he scanned the neighborhood markets a bit more, he might have found more empty boxes. But any more work would have been out of the question for Kim, who suffers from painful degenerative arthritis. His day’s work left him with a cup of instant noodles (1,100 won/US$1.02), a bottle of makgeolli (Korean rice beer) (1,200 won/$1.11), and four 100-won coins to spare.

“Back in the ’80s and ‘90s, I worked at an ironworks, and I was getting by,” Kim said. “After the financial crisis in the late ’90s, the ironworks closed down, and I started slipping. That’s how I ended up like this. But I don’t want to blame anyone. I’m just lazy, and that’s why I can‘t make any more than this. There are lots of people who would love to gather scrap paper but can’t.”

Kim, who lives in a 2.64㎡ flophouse room in Seoul’s Donui neighborhood, has just one other goal in his life: to make sure his poverty isn’t passed down to the next generation. He has often found himself tossed out on the street for failing to pay his 230,000 won (US$213) monthly rent on time, but he plans to continue working for a living even after his knees give out. What he doesn‘t want to do is depend in his son and daughter-in-law.

“They’ve got it tough, too,” he said. “It’s been hard enough for them to pay back the loan for their key money deposit, but I just got a grandbaby a little while back. I don’t care how things are for me, but I can‘t let the poverty be handed down to my grandkids.”

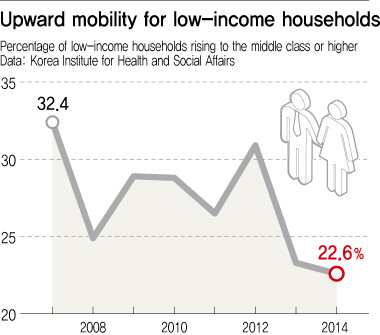

Kim’s wish - breaking the chain of poverty - may seem simple, but recent research data show just how much harder it is getting for people to move from low income to the middle class, or from the middle class to the upper class. Meanwhile, the percentage of households sliding out of the middle class nearly doubled in the three years from 2011 to 2014. In household income terms, becoming poor is easy, while achieving a more affluent life has gotten harder. For Kim, this current level of poverty is both his present and his future.

On Jan. 27, the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA), a state think tank under the Office of the Prime Minister, released a report on its basic analyses of 2014 national welfare panel data. The year‘s figures showed a new low - 22.64% - in the percentage of low-income households rising to the middle class or higher. The rate of households making the leap directly from low to high income was a vanishingly small 0.31%. “Low income” in this case refers to people making less than half the median in ordinary income (the centermost value when all households are ranked by income). Households within 50-150% of the median are classified as middle class, while those earning more than 150% are considered upper class.

While class mobility has gotten harder for low earners, the rate of members of the middle class sliding into low income has increased sharply in recent years. The 2012 study calculated it at 6.14% compared to the year before. The number has continued to grow, with rates of 9.82% in 2013 and 10.92% last year.

Launched in 2006, the national welfare panel examines roughly 5,000 households each year to assess standard of living and welfare demand for different population segments. This year’s study, the ninth overall, was conducted between March and July 2014.

By Choi Sung-jin, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 3‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 4Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 5Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 6Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 7Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 8[Editorial] In the year since the Sewol, our national community has drowned

- 9[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- 10[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent