hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

National incomes rising, but households are tightening their belts

“National incomes are set to reach US$30,000, but it doesn’t feel like there’s much difference between the increase in my income and the inflation rate. I never know when I could be out of a job, I have to prepare for retirement, and I have to start repaying the principal on my mortgage soon. So of course I’m cutting down on my spending as much as possible.”

Last year, gross national income for South Korea passed US$28,000. But to this 48-year-old design company employee surnamed Kim, the Bank of Korea’s announcements about the new high-water mark and imminent era of incomes over US$30,000 seem like something from another country.

National account estimates released by the Bank of Korea on Mar. 25 for 2014 showed a 3.9% nominal GDP growth rate from the year before for the national economy (3.3% in real economic growth). Per capita GNI was calculated at 29,680,000 won (US$26,950), marking an increase of 3.5% (1,013,000 won/US$9,200) from 2013. In terms of dollar value, the US$28,180 total was up 7.6%, or US$2,001. The steep rise in dollar value came thanks to a 3.8% increase in the value of the won last year.

But apart from corporate and government earnings, actual personal gross disposable income (PGDI) for households - an indicator of the condition of the public’s pocketbooks after taxes and pension contributions - rose by just 3.3%, or less than the 3.5% increase in per capita GNI. Real private sector consumption, mostly by households, increased by just 1.8%, well below the real GDP growth rate of 3.3%. It’s a sign that households are tightening their belts and keeping consumption to a bare minimum.

PGDI for 2014 was calculated at 16,626,000 won (US$15,090), with an average of 66,504,000 won (US$60,380) for a family of four. The 3.3% annual growth rate was the lowest since 1998, when a level of 3.2% was recorded in the wake of the country’s foreign exchange crisis, and 2009, when it reached 3.3% amid conditions of global financial crisis. The figures seem to show that whatever benefits growth is producing are not reaching individual families.

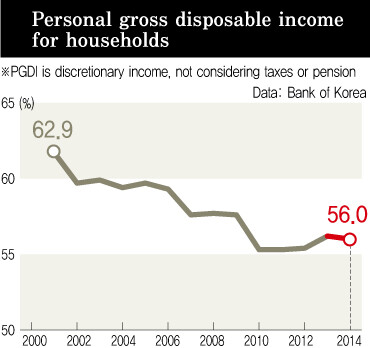

In 2012 and 2013, PGDI rose by 3.4% and 4.5%, respectively - a faster rate than per capita GNI, which grew by 3.3% in 2012 and 3.0% in 2013. Last year, PGDI failed to keep pace with the rise in per capita GNI. As a result, PGDI dipped slightly from 56.2% in 2013 to 56.0% last year as a percentage of GNI. As recently as 2001, the percentage was over 60% (61.7% that year); since then, corporate income has rapidly outpaced household income, sending the percentage tumbling down to the mid-50% range. The OECD average rate stood at 62.6% in 2012, or around seven percentage points higher than South Korea.

Economic conditions in South Korea remain anemic. The real economic growth rate has increased only slightly, from 2.3% in 2012 to 2.9% in 2013 and 3.3% last year. Meanwhile, figures from 2014 showed slack consumption and tightening household belts starting to become a real obstacle to economic recovery. The rate of increase in real private consumption was 1.8%, marking the lowest level since 2009 (0.2%) and a third straight year below 2%. Household income growth remained slow, but other factors appeared to include debt repayment and rising savings to prepare for an uncertain future. The net household savings rate of 6.1% was the highest in the ten years since 2004, when it clocked in at 7.4%.

“A high rate of household savings is positive in terms of economic stability, but the fact that household consumption trends are down for a variety of reasons could become a burden for the economy,” said Kim Young-tae, head of the Bank of Korea’s department of national accounts.

LG Economic Research Institute senior analyst Lee Keun-tae gave a number of factors behind lower spending.

“There’s been an increase in lower-quality service jobs and conditions are worsening for the self-employed, which means household income has not been keeping up with the rise in national income,” Lee explained. “Meanwhile, there’s been continued low growth since the global financial crisis, and when you factor in worries about the future, families just aren’t spending.”

The GDP deflator, which is the most comprehensive measure of inflation, came in at 0.6% for 2014, down slightly from 0.9% in 2013. It was the second straight year of the indicator hovering below 1%.

By Kim Su-heon, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 6Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 7No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 8[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 9N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 10Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government