hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

A Hankyoreh intern’s quest for the meaning of Makgeolli

I’m a little drunk and very sunburned. The two older Korean men I’m sitting with on the concrete bank of a stream in east Seoul are tipsy. One shows me how he can dance on one foot, doing high kicks with the other. We’re on our third bottle of makgeolli.

Makgeolli is rice beer, one of Korea’s oldest alcohols, a fact that many of its elderly consumers eagerly relate with pride. The milky beverage, made from rice, water, and a wheat fermentation starter called nuruk, was first referenced in a twelfth century Chinese Song Dynasty document that describes it as a commoner’s drink, “a thin tasting alcohol of deep hue that does not cause much drunkenness.”

Throughout its millennium-long history, makgeolli has undergone changes in production methods, ingredients, and social connotations. Makgeolli fell to a low point during the Japanese occupation (1910-45) due to laws that taxed and controlled liquor production, and again in the following years due to rice shortages, but in the last decade it has experienced a revival among middle class drinkers and artisan brewers dedicated to preserving its tradition. Still, many others enjoy the brew at family gatherings and in natural settings like near mountains and streams.

To find out just what people thought about makgeolli I set out on my bicycle. My first stop was the stream where I met the two Korean men, who, before I could explain that I only wanted to ask them a few questions, put a paper cup in my hand and filled it to the brim. Thus began my journey.

The Elder

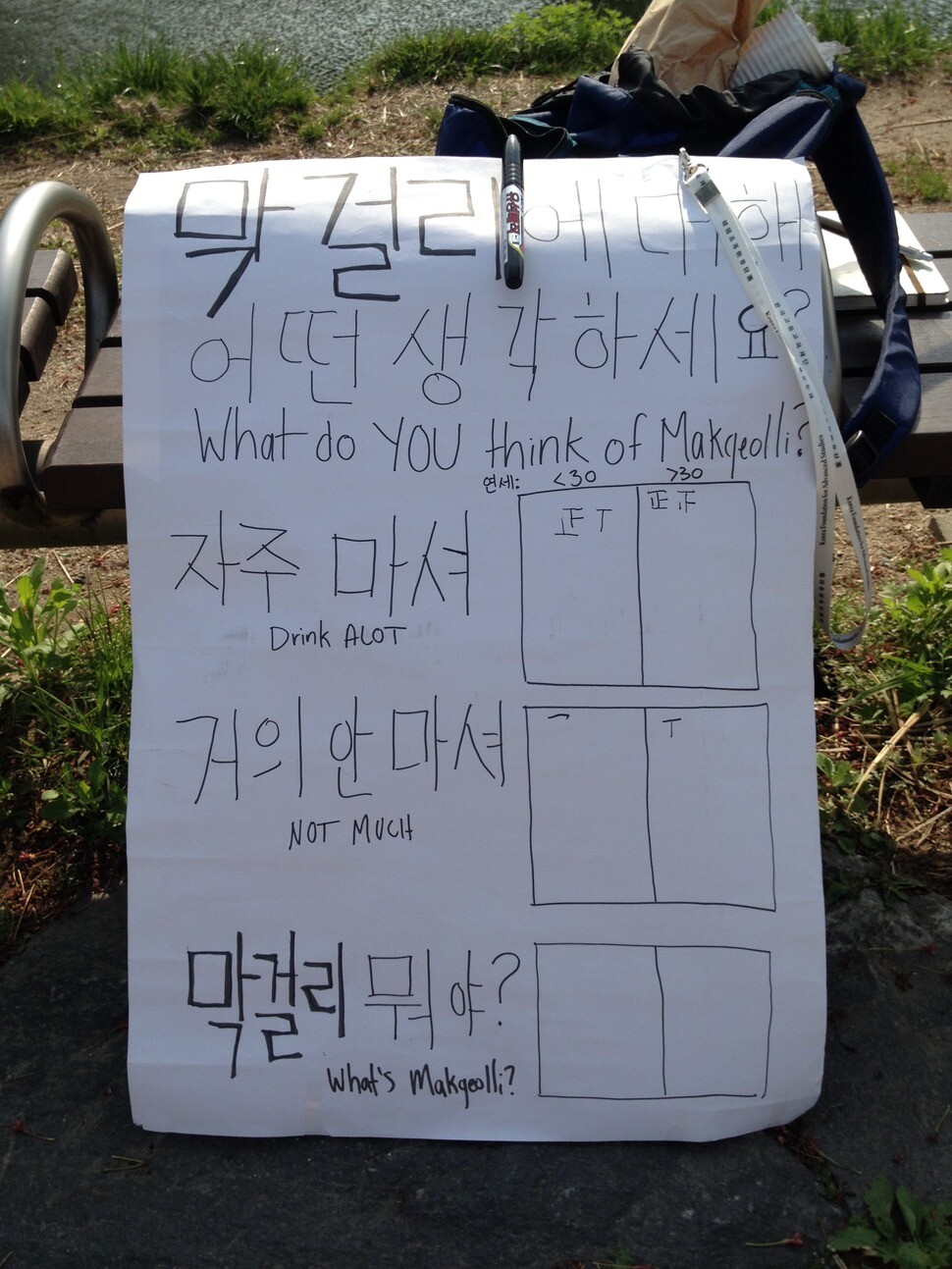

The next day I returned to the stream with a sign that read in sloppy Korean, “What do you think of makgeolli?” I talked to many amused Koreans who stopped to check boxes indicating how frequently they drank makgeolli. Most of the people who passed me stared, some made a small comment, others laughed and went on their way. Nearly everyone I talked to was over 50 years old. By the end of the day I had a surprisingly cohesive picture of one of makgeolli’s largest consumer groups.

“After working in the countryside, you drink makgeolli. When you feel thirsty, you drink makgeolli.”

Intrigued by my project, a middle-aged man stopped and explained this to me. He told me that makgeolli is a farmer’s drink, that it gives one power to work, and keeps your body healthy. These were words I would hear again and again.

One of the most excited passersby I encountered was an elderly gentleman in a suit and flannel cap who made giant circular motions with his arms to explain how easy makgeolli is to digest.

“Makgeolli doesn’t hurt your stomach like other alcohols. We drink it because it makes your stomach feel full.”

He was 97 years old, his wife told me, and they drank makgeolli every day to stay healthy.

Makgeolli’s health benefits were reiterated by many other Koreans, yet a few said otherwise. One man had recently given up his daily makgeolli habit because of the adverse effects to his body. Another older woman explained to me that these days makgeolli causes headaches because the ingredients are not what they originally were.

Over the course of four hours I surveyed around fifty Koreans, most past middle age. Except for the man who had stopped drinking, all of the males responded enthusiastically and said they drink makgeolli often. Most elderly women also said they drink often, while middle-aged women were more opposed, many preferring beer.

I asked one elderly Korean woman when she usually drank makgeolli. Her answer, “Anytime after 4 pm.”

The young generation’s disinclination toward makgeolli

On a tip from a pleasant silver haired woman, I peddled across the bridge to Hanyang University. She had disappointedly explained to me that nowadays students are not interested in makgeolli, choosing soju, a Korean distilled liquor, or beer, over the traditional drink. It was nearly dinnertime and classes were finishing; I took my sign and found the last patch of sun outside the school library.

The university students were less talkative, but like the people on the stream path there were similarities that ran throughout their responses. They did not speak of makgeolli’s health benefits or proudly relate its long history. There was no mention of the countryside or farmers. Instead, when asked what they associated with makgeolli, they answered rainy days, pajeon, a Korean green onion pancake, and headaches.

Many students confirmed the elderly woman’s fears. “I don’t like it because of the smell.” “I usually drink cocktails.” “We prefer soju.” Those with these views remarked that makgeolli was a drink for old people.

Yet many others disagreed. One girl insisted that she drank makgeolli every night of the week. Others were less extreme, but when given two choices of “drink often,” or “not much,” they opted for the first option.

By the end of the day I had surveyed 88 students. While ten, including three exchange students, reported never drinking makgeolli, the rest were split almost evenly. Half answered to frequently drinking makgeolli, and half responded in favor of other alcohols. University students’ preconceptions of the drink varied from those of their grandparents. Makgeolli seemed less culturally significant to the students. The adjective I heard most at the stream was, “refreshing.” On campus the prevailing word was, “hangover.”

The young and old generation shared one thing. When asked what kind of makgeolli they usually drank, the answer was always the same: Seoul Jangsu Makgeolli.

Trying to get rid of aspartame

Elbow deep in a goopy mixture of rice, water, and nuruk, I met two non-Koreans passionate about makgeolli: Julia Mellor, co-founder of Makgeolli Mamas and Papas (MMPK), an online resource for all things makgeolli, and Becca Baldwin, a makgeolli brewing instructor. They led me and nineteen other expatriates through the makgeolli making process at Susubori Academy, an organization that teaches traditional Korean brewing methods in Seodaemun district.

Julia and Becca are concerned with the current state of the makgeolli industry, and trying to educate foreigners and Koreans alike about the drink. The cause of their concern is aspartame, an artificial sweetener only introduced to makgeolli in the last fifty years. Of everyone I spoke to, the foreigners at Susubori were the people most concerned with preserving makgeolli’s tradition.

After cleaning our forearms of remaining goo, Julia explained to me that aspartame entered the makgeolli market to disguise changes that occurred due to long periods at high temperatures during shipping. When the problem was resolved through refrigerated shipping, brewers continued adding aspartame, sweetening their wares to appeal to Korean palettes.

Flicking a piece of rice slop from her hair, Julia insisted that aspartame was a bane on the industry, by creating what she describes as a “giant dark area,” a black hole, of makgeolli that all tastes the same, including the ubiquitous green bottled brews.

“There is nothing distinguishing between them because they are using a heavily watered down recipe and using artificial sweeteners.”

Julia and the other non-Koreans at Susubori are vehement about the subject. They are not the only ones.

The makgeolli industry hopes for another boom

Baesangmyeon Brewery has dedicated itself to making alcohol in a traditional Korean style since opening in 1996 in Seoul. In an email interview, Lee Eun-kyung of Baesangmyeon Brewery’s brand management team, wrote that the contemporary makgeolli market has plummeted due to Seoul’s infatuation with craft beer.

Lee says that more and more people are choosing craft beer over makgeolli. “In times like these, the industry leaders must overcome the present difficulty through pride of Korea’s most representative alcohol and by taking an active position. For makgeolli’s advancement, it is not only the industry officials, but also foreigners’ interest, that together might bring makgeolli to another boom.”

Julia and the folks at Susubori also envision another makgeolli boom, and like Lee Eun-kyung, believe foreigners will play a key role to makgeolli’s success. Julia told me this is because foreigners do not have the preconception of makgeolli that Koreans do. Non-Koreans are less likely to expect a cheap, sweet alcohol, and they don’t associate makgeolli with being low-class or old-fashioned.

“Once the western market starts to pay for [artisan makgeolli], the Korean audience will probably change.” Change in the Korean consumer will lead to change in the brewers, Julia continued, less aspartame and more diversity between brews.

The many faces of makgeolli

When our three green bottles of makgeolli were dry and the sun had disappeared behind the skyscrapers, I bid my two new friends at the stream farewell. On the ride home I made one last stop. Strolling through Sinseoldong’s flea market, I met a man drinking something murky from a two-liter water bottle. He said it was makgeolli, made at home and bottled that morning.

He offered me the last of it in a well-used paper cup. It tasted dry, stronger than the Jangsu Makgeolli that lingered on my tongue. A curious crowd formed around us. A young Korean couple stopped to take pictures. Two foreigners looked on. A man in a blue suit shook my hand vigorously, repeating the words, “Korean number one wine.” Everyone was excited to talk about makgeolli. Everyone had something different to say.

The crowd at the market represents makgeolli better than any one individual could. It is a drink that means different things to different people- the old, the young, the foreigner, the artisan. Its meaning lives in those who brew it, drink it, and share it.

By Dan Sizer, Hankyoreh English intern

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong? [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/8517133419684774.jpg) [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?![[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/6817133413968321.jpg) [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 3[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 4[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 5S. Korea, Japan reaffirm commitment to strengthening trilateral ties with US

- 6Korea, Japan jointly vow response to FX volatility as currencies tumble

- 7Gangnam murderer says he killed “because women have always ignored me”

- 8Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 9[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 10‘Right direction’: After judgment day from voters, Yoon shrugs off calls for change