hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Memoir] The 24-year struggle to clear Kang Ki-hoon’s name

When I hear the KakaoTalk alert, I open the application to find that one of my friends has sent me a picture, along with a message that says, “24 years ago…groan.” My friend tells me the picture had been posted on someone’s Facebook page.

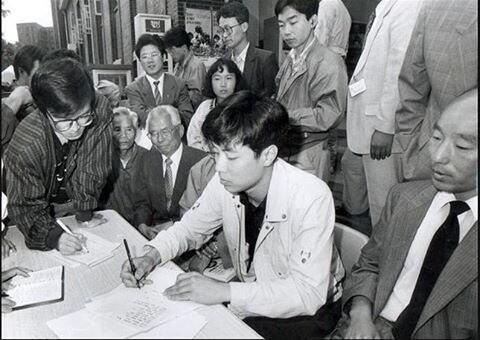

In the middle of the picture [above] is Kang Ki-hoon, and standing on the far left, wearing horn-rimmed glasses, is me. The picture was taken at a press conference for Kang, who was doing a sit-in at Myeongdong Cathedral after being framed for ghostwriting a suicide note.

My memory of the occasion is a little fuzzy, but I think that Kang was copying the suicide letter to show that his handwriting was different. With all the cockiness of a rookie reporter, I was busily scribbling down notes off to the side.

In the photograph, I look really unfamiliar. Today, my hair is thinning and my belly is bulging, but at 28 years of age, I didn’t look half bad, I think. But as soon as I look closely at Kang Ki-hoon, I realize with sudden embarrassment just how frivolous it is to be concerned about how much I’ve aged.

The Kang I see in the picture looks youthful, even boyish. When I saw him back then, I remember thinking how neat and tidy he looked. But his charming appearance was undone by the 24 years of pain and humiliation that he had to endure after the unfair ruining of his reputation.

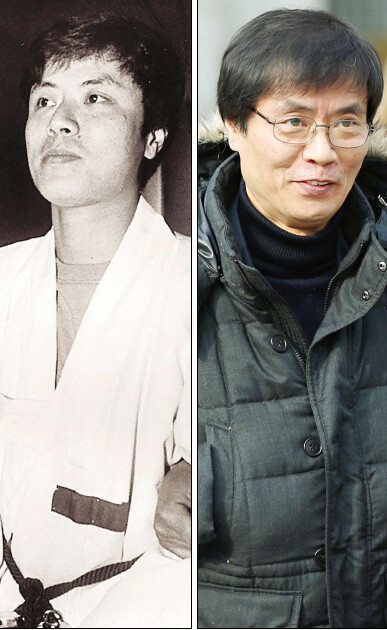

I visited Kang Ki-hoon one time in the hospital after hearing that he was sick. I looked around the hospital room where he was supposed to be staying, but none of the patients looked familiar. It was not until he greeted me that I realized which one was him.

In my memory, Kang was a strapping man with a fair complexion; but the man standing before me was stooped over, his face jaundiced. His eyes were deeply recessed, with dark circles beneath them.

Kang was ill with liver cancer. The ongoing sense of injustice, the guilt of watching his parents die in quick succession, and his financial difficulties had gnawed away at his body.

If Kang had only been able to get regular health checkups, the doctors might have noticed the troubling signs in time. But Kang’s lack of financial stability - he sometimes worked as a day laborer on construction sites - did not allow that kind of luxury.

“In the 21 years since the trial, I haven’t felt happy even once. May is when it all happened, and every May I feel sick in both body and soul,” Kang bitterly said during my visit.

"Stress weakened his immune system, and that made his illness worse,” said a doctor who is familiar with Kang’s condition.

This weekend, I gave Kang a call. At first he didn’t answer, but on the third or fourth time he finally picked up his cell phone and said he hasn’t been taking calls from reporters.

But now that I had him on the line, there was virtually nothing that I wanted to know. At last I managed to ask why he hadn’t been present when the Supreme Court read its verdict on Thursday.

“I just didn’t want to play second fiddle,” Kang said. After this laconic answer, we were both silent for some time.

I asked Kang a few questions about his health and ended the conversation. He asked me not to write an article about him, but the fact is there’s hardly anything for me to say.

Should I say that justice was served after 24 years? That the truth will always be victorious? But I find myself wondering how on earth this has changed anything.

In Feb. 2014, when the Seoul High Court found Kang not guilty, he attended the press conference. At the time, he had a bold request to make. “The prosecutors who handled my case probably remember me. I would like them to express their remorse one way or another,” Kang said.

But the only response the prosecutors made was to appeal the case to the Supreme Court. Kang sarcastically suggested that the prosecutors were just hoping he would die.

Even after the Supreme Court made its decision, the prosecutors remain cocky. “I don’t think this is the kind of thing that requires an apology,” said Nam Ki-chun, a lawyer who was one of the prosecutors that first investigated Kang Ki-hoon, in a telephone interview with the Kyunghyang Shinmun, a liberal newspaper.

“If we apply the standards of the present to the decisions of the past, the conclusions will be different. Under a modern rubric, we would even have to reverse many of the decisions made by Sejong the Great of the Joseon Dynasty,” Nam said.

The same applies to the courts. After the Seoul High Court first decided to hold a retrial of the case in 2009, it was not until three years later that the Supreme Court made the final decision to move ahead with the retrial. After Seoul High Court cleared Kang of charges in Feb. 2014, it took the Supreme Court another year and three months to render its final decision.

I perused the Supreme Court’s decision to try to figure out what had taken so long, but it is little more than a summary of the High Court’s decision. The court did not offer Kang a single word of contrition or consolation. The court’s attitude seemed to be that the flood of evidence exonerating Kang left it no choice but to find him not guilty.

Some newspapers went even further. “The judges’ different subjective opinions about how to view the results of the National Forensic Service’s handwriting assessment resulted in completely opposite conclusions in the trial. Judgments about the reliability of evidence can differ, of course, from one judge to another. In the end, it is Kang who knows the truth,” the conservative Chosun Ilbo said in an editorial.

What is the Chosun Ilbo’s comment about only Kang knowing the truth supposed to mean? The Chosun Ilbo is always pontificating about the rule of law; does it mean to say that it refuses to accept the verdict of the Supreme Court? Does the Chosun Ilbo mean to say that it cannot offer a modicum of courtesy to a person whose life was destroyed, not even as a newspaper that played a role in that destruction?

Perhaps it is because of this atmosphere that Kang Ki-hoon no longer has the energy to be angry. The day that the Supreme Court read its decision, Kang was conspicuously absent.

I suppose he didn’t want to relive his continuing humiliation. At least, that‘s how I took his remark about not wanting to play second fiddle. It was not until four days later, on May 18, that Kang released a short statement that expressed his position.

My own connection with Kang Ki-hoon began on May 18 exactly 24 years ago. A funeral was held that day for Kang Kyung-dae, who died after being struck by police with a lead pipe during a demonstration. I was following along with the funeral march to cover the story when I heard a loud beeping. It was an order: to find Kang Ki-hoon and bring him back to the Hankyoreh offices. I happened to see him there in the crowd, and I went over to grab his wrist and get him into the company car. Right away, one of my co-workers showed him the suicide note left by Kim Ki-sul when he jumped to his death. He asked Kang to copy it, and he did so then and there. At the time, we had no idea of the seriousness of the situation. A reporter at one evening newspaper printed a story comparing the handwriting samples and noting that they were entirely different, and I concluded that they simply had an overactive imagination.

From then on, Kang Ki-hoon was my beat. I sought out a handwriting sample for Kim Ki-sul and asked some private analysts to help get the false charges against Kang dropped. Every time a new sample of Kim’s handwriting emerged, my hopes rose. ‘Surely the prosecutors will call off their investigation now,’ I thought. But every time it failed. Every piece of evidence that was located they dismissed as a forgery. It happened when a notebook Kim kept for the National Democratic Movement Union (NDMU) turned up. Anyone who saw it would know it was the same handwriting on the suicide note. I rode with the attorney Lee Seok-tae (now chairman of the special Sewol investigative committee) to the Prosecutors’ Office to hand it over. I can still remember Lee’s reassuring face on the way over. “It’s all over now,” he said. I’ll also never forget the bewildered look that came across prosecutor Shin Sang-gyu’s face when he received the notebook. But a few days later, the prosecutors were insisting that even that notebook was something Kang had hastily forged. “The perforations don’t line up,” they said. We were back to square one.

I also remember traveling all around Seongnam one time to see Kim’s girlfriend, a woman surnamed Hong. She was a key witness, someone who could sway the very outcome of the case, and I was tipped off that the prosecutors had whisked her off to lay low at a house in Seongnam belonging to someone with the surname Pyo. “’Pyo‘ isn’t like ‘Kim’ or ‘Lee,’” I thought. “It‘s not a really common name. I should be able to track her down.” I went around to every neighborhood office in Seongnam and located all the houses registered to Pyos. It was around the point my feet started to ache that I saw another nameplate marked “Pyo” on one of the houses. The moment I stepped inside, I was intercepted by a burly detective. “There was a rape nearby, and you look like the suspect,” he said. “You’re going to have to come with me to the police station.” On the way over, I dashed out of the station and raced back to the Pyo house, but I was slower than the police. I was captured and dragged back. That night, the prosecutors admitted they were keeping Hong under guard, but by then she had already been relocated.

All those things live on today as bitter memories. If I felt that way as a reporter, I can only imagine what it was like for Kang Ki-hoon, or for the other members of the NDMU. On May 14, I visited the Supreme Court for the final sentencing day. I could see a lot of the old NDMU staffers, including venerable former leaders like Lee Chang-bok and Lee Bu-yeong. We’d all waited so long, but the outcome was simple. “In case No. 2014-Do-2946, the prosecutors’ appeal against the defendant Kang Ki-hoon is hereby dismissed,” the Justice said, and that was it. Even as we quietly exited the courtroom and clasped hands, all I could think was, “Is that what we waited 24 years to hear?”

From there, it was on to an early lunch, where glasses of makgeolli (Korean rice beer) were quickly passed around. Toasts were made to stories about Kang Ki-hoon. Kim Seon-taek, an NDMU official who had been framed as a “mastermind” of Kim’s death because of a passage in the suicide note about “entrusting all future affairs to Kim Seon-taek and Seo Jung-sik,” talked about the two-and-a-half years he spent as a wanted man and the hardships of a life spent moving between guest rooms at cheap motels. At a certain point, he said, he felt so tired that he just wanted the police to catch him already. Even now he hates the smell of inns, he added; no matter how much he’s had to drink, he’ll take a taxi home. Lately, he has been living in Chungcheong Province, and his taxi fare the day before last came out to over 100,000 won (US$92). The glasses went round and round, until finally the tears started to flow. It was Kang’s younger sister. “If only he had gotten healthier,” she said. “I’d give everything I have. My brother. . . .” Everyone grew quiet. Kang’s sister explained that she is a lawyer who works today as a human rights advocate for North Jeolla Provincial Office.

As someone who had been a reporter back in the day, I received a few glasses of makgeolli before I started feeling tipsy. I was gathering my things and making an early exit when I felt my legs weaken. I began to reel. I felt terribly hungry, even nauseous. It isn‘t just the makgeolli, I thought. Outside, the May sun was shining so bright I thought I might go crazy.

By Kim Eui-kyum, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 7[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 10[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father