hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

A time of regression: S. Korea’s democratic rankings slide

It’s a time of regression. Basic rights are being trampled; institutions are backsliding. Political freedoms are shrinking while young people shiver in deprivation, their dreams dashed. The despairing lamentations of today‘s “Hell Joseon” - a new coinage meaning “Hell Korea” - brim with hate and hostility, while the political system that is supposed to resolve conflicts has long since fallen into a state of suspended animation. A crisis of democracy - there seems to be no other way to describe the reality today. It’s the grim landscape wrought in South Korean society today by two years and ten months of a brute force administration under President Park Geun-hye.

On Nov. 5, the United Nations committee for the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) rated South Korea as warranting “concerns” or recommendations for improvement in 25 of 27 categories in its review of the general civil and political situation. It voiced particular concerns about freedom of association, noting such serious restrictions on the right to peaceful assembly as a “de facto system of authorization” for assemblies and the “usage of excessive force [and] car and bus blockades.” It added the recommendation that the “State party should ensure the enjoyment by all of the freedom of peaceful assembly.”

But the ink had scarcely dried on that recommendation when another vehicle blockade went up on schedule for the first popular indignation rally in downtown Seoul on Nov. 14. Clashes between police and demonstrators left one farmer in his sixties on the brink of death after being blasted by a water cannon jet. Investigators are now considering Korean Confederation of Trade Unions president Han Sang-gyun - described as the “orchestrator” of the rally - for sedition, a crime that has existed merely on paper for close to three decades. It doesn’t get much more regressive than that.

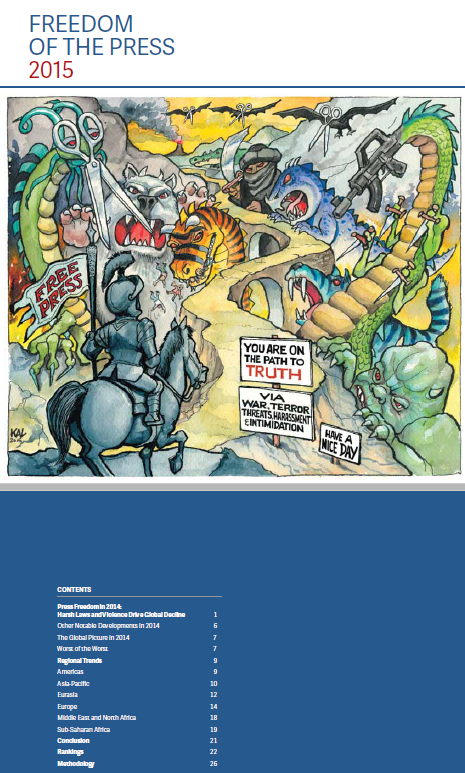

Meanwhile, all the indicators of a mature democracy have plunged. A ranking of press freedoms by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) showed South Korea in sixtieth place, down three rungs from last year. It’s a slide that has been under way for four years now. Freedom House, an international human rights watchdog group, lowered South Korea‘s press classification from “free” to “partly free.” The same group’s assessment of political rights last year saw South Korea‘s rating sink from 1 to 2 for the first time in nine years.

What brought on this decline in a democratic system that was once touted as a model for other Asian countries? There are various diagnoses. Many blame Park’s lack of understanding of democracy and imperial style of authoritarianism. Others point the finger at the opposition and progressives for their incompetence and failure to take action on - and even encouragement of - the regression. But the current overall slide doesn’t seem to be traceable to any one single factor.

Youngsan University political science professor Chang Eun-joo uses the term “illiberal democracy” to describe the system in South Korea today. This means that while the country has achieved democracy in procedural terms, the institutional foundation in terms of separation of powers, fair reporting, and a mature civil society remains weak, resulting in even such fundamental aspects of a liberal democracy as freedom of assembly, association, and expression being threatened according to the leanings of those in power.

“Some people are worrying that South Korea is coming to resemble the Japanese model of long runs in power by conservatives, but that’s a mistake,” Chang said. “It‘s more akin to the countries that have established neo-authoritarian systems based on democratic procedures, places like Russia, Hungary, and Turkey.”

The assessment is that South Korea has only the basic frameworks of liberal democracy in terms of regular elections and party competition, while the political lives of its people are no different from what they were during the authoritarian era - a democracy solely in term of elections, in other words.

Some have argued that the current political crisis should be viewed through the lens of the general economic and social crisis afflicting South Korea today.

“The crisis in democracy can’t really be separated from the market-first mentality that minimizes the role of politics, or from the neoliberal order that results in such extreme inequality and political polarization,” argues Keimyung University Professor Lim Woon-taek. By this analysis, the political slide that has taken place under the Park administration can‘t simply be called the President’s “Season 2” or a return to the Yushin system of the past.

Given the complexity of the causes, experts agree that any response or alternative should be equally varied.

“A neo-authoritarian system that arms itself with election-based legitimacy can only be woken up by an election,” said Chung-Ang University professor Shin Jin-wook.

“Breaking down the antipathy voters feel toward political engagement is every bit as important as anything politicians and their supporters can do to build the opposition’s capabilities and change the system,” Shin added.

It’s a call for greater efforts from politicians and civil society to rouse citizens from cynically dismissing politicians as “all the same,” from despairing that their vote can’t change the system, and from fearing that expressing their opinion could get them in trouble.

By Lee Se-young, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 3‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 7Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 8[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 9[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 10[Editorial] In the year since the Sewol, our national community has drowned