hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] 24 hours at the comfort woman statue vigil

Since the announcement of the Dec. 28 agreement between Korea and Japan, which included a call for “appropriate resolution of the issue of the statue of a young woman,” hundreds of people have been gathering in front of that statue, across from the Japanese Embassy, in Seoul’s Jongno district every day. The Hankyoreh observed the site for 24 hours from 9 am on Jan. 4 to 9 am the following morning and found that the statue is never alone, as crowds of citizens come to express their feelings of regret and gratitude.

Jan. 4, 10 am: “We are sorry.”“The statue’s raised heels, with only the balls of her feet touching the ground, symbolize the fact that when the comfort women returned home, they were shamed and were not able to move about freely and comfortably.” People nod their assent as they listen to the explanation given by Jeong Su-yeon, 28, who has stepped forward to act as a docent. Insisting that the Dec. 28 agreement between the foreign ministers of Korea and Japan is invalid, a group of young people staging a sit-in in front of the statue are operating as volunteer guides to explain the statue’s significance to people who gather there. Jeong says, “While telling people about the statue, I’m ashamed to admit that previously I wasn’t that concerned about the suffering that the elderly comfort women had gone through.” Kim Jeong-hwan, 38, who has been listening to Jeong, says, “I work in an office near here, and though I pass by the statue every day, I never properly understood its meaning before. I feel sorry that I ignored the pain and suffering these women went through for such a long time.”

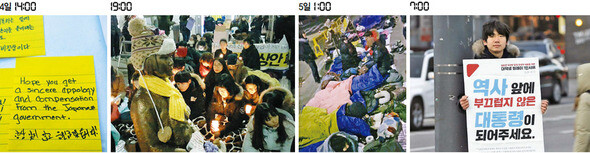

Jan. 4, 2 pm: “We will remember.”“We erect this monument of peace to commemorate their history and their noble spirit.” Kang Eun-su, 33, who has come all the way from Cheongju, North Chungcheong Province, slowly reads the words engraved below the statue to her son, Park Ju-hyeong, 7, and daughter, Park Da-yeong, 4. Kang says, “I thought that just seeing the statue would be a good lesson in history for my children, so I took off some time from work to bring them here.” Lee Gi-uk, 26, has brought his Canadian friend Emily, 26, to the site of the sit-in. Hearing Lee’s explanation of the statue, Emily tearfully says, “This is a tragedy that must never happen again.”

Jan. 4, 7 pm: “We will watch over you.”“We are the elderly ladies, the young girls, the masses of people. Join hands and watch over the peace statue of the young woman.” From the stage, university student Park Min-hoe, 23, leads a gathering of more than a hundred people holding candles in song. Park says, “I made the song by changing the lyrics of a song I used to sing with some elderly women in Miryang.” The area around the statue is the most crowded at seven each evening during the Candlelight Cultural Festival for the Nullification of the Korea-Japan Agreement. Lee Myeong-ok, 59, one of the participants, says, “The statue of a young girl is a way for the people of the nation to apologize to the comfort women and remember their part in history. Though our government may not always get history right, acting as an accomplice in Japan’s efforts to erase this part of history is shameful.”

Jan. 5, 1 am: “We’re in this together.”“They aren’t much. I just felt bad for the trouble these students are putting themselves through,” says one person who wishes to remain anonymous. He is carrying a black plastic bag containing five boxes of Choco Pie. “I work as a designated driver for hire and just stopped by for a minute between clients. This is a problem that my generation should have already taken care of, so I feel bad for these students who spend all night demonstrating here.” He speaks quickly and then disappears into the darkness between nearby buildings. The young people have been staying by the statue till dawn every day since Dec. 30. Cho Ji-yeon, 23, speaks from inside a sleeping bag with a firm expression on her face: “The comfort women must have suffered miserably in colder places than here, so I can put up with this cold weather. The support of so many people keeps us strong.” Behind her is a pile of snacks and hot packs that people have left for the group.

Jan. 5, 7 am: “Together we’re strong.”“Let’s get up.” At seven in the morning, it is still dark in Seoul as the young people emerge from their sleeping bags on the cold ground. With eyes only half open as he rolls up his sleeping bag, Lee Gwan-ho, 21, says, “It was colder than I expected, so I didn’t sleep at all.” Smiling brightly, he adds, “I just hope our vigil here will be of some small help to the former comfort women.” For the morning rush hour, they disperse, picket boards in hand, to carry on one-person demonstrations around Seoul. Kang Ji-eun, 23, is going to Gwanghwamun intersection. His board says, “Become a president who does not stand in shame before the facts of history.” As people on their way to work glance at Kang, he affirms, “I want to make more people aware of the issue of the comfort women and keep history free of distortion.”

By Hwang Keum-bi and Kwon Seung-rok, staff reporters

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 7Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 8[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 9[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 10‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be