hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Young couples face an increasingly expensive housing market

Newlyweds “Kim Min-jae,” 30, and “Lee Su-jin,” 29, live in a unit of multiplex house in the Sindaebang neighborhood of Seoul’s Dongjak district. The unit measures 33 square meters, for which they put up a key money payment of 140 million won (US$115,800). Key money is a rental method used in South Korea in which the tenant gives the landlord a large sum - usually at least half of the purchase price - instead of paying monthly rent. The tenant receives the entire deposit back upon the completion of the contract. The couple received 20 million won (US$16,500) from Kim’s parents, who raise cattle in Gochang, North Jeolla Province, and he also carried over a deposit of 30 million won (US$24,800) from his previous studio apartment, but they still found themselves 90 million won (US$74,400) short. They also face student loans of seven million won (US$5,800) that need to be repaid.

The couple finally opted to take out a loan for 97 million won at an annual interest rate of 2.79%. With Kim in his fourth year in an administrative position at a small IT company and Lee working as a councilor for the district office, their combined salaries amount to just over four million won (US$3,300) a month.

It’s a slightly higher amount than the average for a two-person urban worker household, which stands at 3.729 million won (US$3,084) for 2016. But with plans to repay at least 40 million won (US$33,100) of the loan within the next two years, the couple decided they would need to spend about half their income paying it down.

“Park Hyeon-su,” 35, and “Choe So-yeon,” 32, married in May 2015. Their first home together is an apartment in Seoul’s Jongno district with an actual floor area of 99 square meters. Park’s father, a retired corporate executive, put up the 400 million won (US$330,800) for key money.

Both professionals, Park and Choe make around six million won (US$5,000) a month combined. Of this, they give around 200,000 won (US$170) to their parents and spend two million (US$1,650) on living expenses, 300,000 won (US$250) on apartment costs, and a combined three million won (US$2,480) on transportation, communications, and other expenses; the rest goes into savings. They currently predict that if they save up over the next five or six years, they will eventually be able to purchase a nearby apartment costing around 600 million won (US$496,200) without a loan by carrying over their current 400 million won key money deposit.

Simply being a South Korean newlywed in 2016 may mean they are among the lucky ones. With more and more young people giving up on the idea of marriage due to bleak prospects for finding a job and housing, the fact that a couple marries at all may mean they’ve at least solved those two pressing issues.

But when newlyweds start looking for a home, they find the race beginning all over again.

The soaring cost of houses - both for those looking to buy outright and for those looking to put down key money - creates an almost unbridgeable gap between those who can receive financial aid from their parents and those who have to take out a loan to cover the key money.

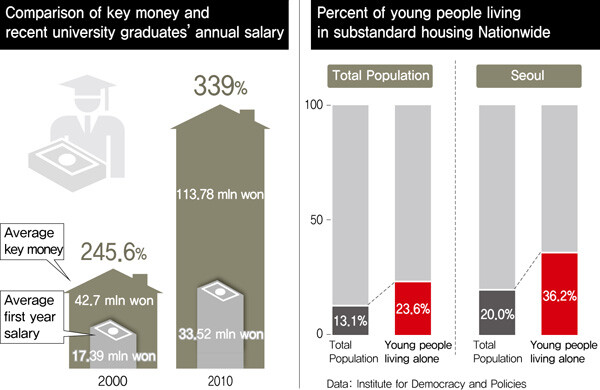

According to a policy paper about the residential status of young households in Seoul that was published in 2014 by the Institute for Democracy and Policies, the average key money in 2000 was 42.71 million won (US$35,350). This was 245.6% of university graduates’ starting salary of 17.39 million won (US$14,400).

By 2010, however, key money had gone up to 113.78 million won (US$94,119), while university graduates’ starting salary had only increased to 33.52 million won (US$22,726). By then, key money stood at 339% of yearly income.

According to statistics about average rent and key money prices from 2011 to July 2015 released last year by Rep. Kim Sang-hui with The Minjoo Party of Korea (formerly the NPAD), the average key money put down for one square meter jumped from 2.65 million won (US$2,192)to 3.37 million won (US$2,787)over the past four years and seven months. For those paying rent along with a substantial deposit, rent only went up slightly from 500,000 won (US$413) to 530,000 won (US$438), but their deposit jumped from 46.37 million won (US$38,356) to 81.19 million won (US$67,158).

Back when key money prices were not so high, newlyweds could pay off the deposit after getting married by putting aside part of their income, as long as they had some savings to begin with or some help from their parents. This key money also served as the seed money for buying their own house down the road.

But with families having to take out bigger loans because of the rising price of housing and with landlords asking for more key money at the end of each two-year contract, it is getting harder for families to cover the increase in key money with their savings alone.

No matter how fast they run, these families are stuck on the treadmill. Meanwhile, young people who lack the resources to put down key money are stuck scraping together enough money to pay their monthly rent.

According to a 2014 study by Statistics Korea, the percentage of rent payers under the age of 30 who took out a loan for a housing deposit (as opposed to those only paying key money) increased from 16.6% in 2010 to 40.4% in 2015. The percentage of couples starting their married life paying monthly rent on top of a deposit was only 3.9% among high wage earners, but 18% among low wage earners.

If you start out the race at the back of the pack, it is hard to catch up later on.

“Looking ahead to our retirement, we’re thinking about making some additional investments to increase our assets instead of pouring everything into savings,” Park and Choie said.

“It’s hard for us to save anything extra while we’re paying off our loan. It looks like we’ll have to refrain from eating out or going on trips for the time being,” Kim and Lee said. If their landlord raises their key money two years from now, they might have to take out an even bigger loan.

These families have different ideas for the next generation as well. Kim and Lee are not planning on having any kids for the next few years, but Park and Choe said they are thinking about having a baby sometime in the next year.

You have to wonder how far the paths of these two families will diverge.

By Choi Woo-ri, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 6N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 7[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 10[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent