hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

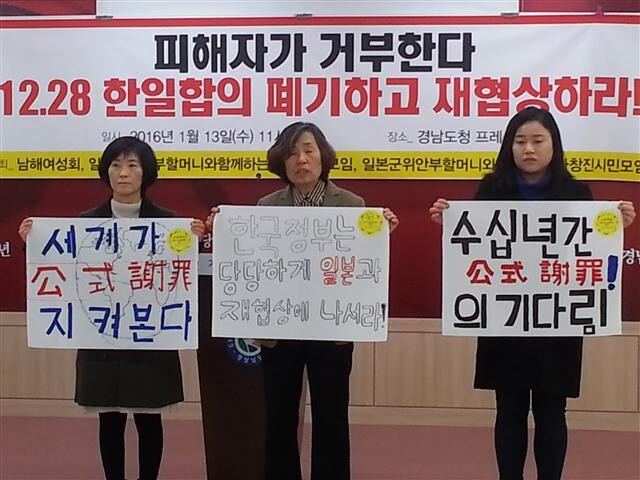

Park’s claims defending comfort women settlement fail to convince

In her New Year’s press conference on Jan. 13, President Park Geun-hye praised a Dec. 28 agreement on the comfort women issue between South Korea’s and Japan’s foreign ministers as “the best possible effort at an agreement.” But now many are calling the deal a “diplomatic disaster of her own making” - a case of Seoul risking everything on unreasonable concessions. Park’s claims that previous administrations “failed to address the issue adequately” and “even gave up on it” are similarly false.

In 2005, the administration of then-President Roh Moo-hyun became the first to argue that the issue had not been resolved by the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations with Japan, a claim it supported with the release of related diplomatic documents from the talks. In Aug. 2011, the Constitutional Court declared the South Korean government’s failure to take diplomatic action to resolve the comfort women issue “unconstitutional,” sparking the first discussions between the South Korean and Japanese governments.

The administration of Roh’s predecessor Kim Dae-jung also took action in 1998 by raising the “lifestyle stability subsidies” to comfort women survivors from 5 million won (US$4,100) all the way to 43 million won (US$35,600). The move had the aim of pressuring Tokyo into acknowledging legal responsibility, serving as a response to the Asian Women’s Fund established in Japan to provide compensation.

Before that, then-President Kim Young-sam had declared in Mar. 1993 that Seoul would not demand material compensation from Tokyo. The message was not that South Korea was “giving up” on the matter, but that it didn’t need the money; what it wanted instead was a thorough investigation and acknowledgement of legal responsibility.

It was during the administration of Kim’s predecessor Roh Tae-woo that Japan first officially acknowledged military involvement in the drafting of comfort women with a statement by then-Chief Cabinet Secretary Koichi Kato in 1992 -- meaning that the Dec. 28 agreement was not the first time Seoul succeeded in getting such an acknowledgement. Park’s predecessor Lee Myung-bak also brought the comfort women issue up with Japan’s Prime Minister as part of the official agenda for the first time since Liberation in a summit meeting held after the 2011 Constitutional Court decision.

Speaking in her celebratory address for March 1st Movement Day in 2013 early in her term, Park declared that “the historical positions of aggressor and victim cannot change even if a thousand years of history go by.” Her administration subsequently made resolution of the comfort women issue a “prerequisite” to improving ties with Tokyo. But it also went on to deliver a favorable assessment of an Aug. 2015 statement by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe that contained no apology for his country’s colonial rule, and when the Dec. 28 agreement was reached after a Nov. 2 summit meeting with Abe, it declared the comfort women issue “finally and irreversibly resolved.” In a sense, it wagered everything on the issue, only find itself pressured by US demands for better ties with Japan into rushing to abandon its own position and presenting the terms of its agreement - unacceptable to the comfort women survivors themselves - as “the best possible.”

“If they want to argue that this has been a better strategy for resolving the comfort women issue than those of past administrations, they would need to make a determination on whether it’s better to reach a conclusion with this kind of an agreement or to just to leave it as an unresolved issue,” said Lee Sin-cheol, a research professor at the Sungkyunkwan University Center for East Asian History.

“Had they left the issue alone, they might have been able to give South Korea a bigger voice in the international community,” Lee added. “The problem is that nothing in the agreement offered a diplomatic achievement capable of taking its place.”

By Kim Jin-cheol, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 4Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 5[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 6Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 7[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 8Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady