hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

9 of 10 suicides show warning signs in advance

The questions would come out of the blue: “If I’m not here, how are you going to support yourself?” Other times, he would start lecturing the kids about things that were way over their head. “In this cruel world,” he would say, “brothers have got to look out for each other.”

It was only after his suicide that his wife realized that all of these comments had been warning signs. He had complained about the troubles he faced at his job, and he was on the way to work on the day that he ended it all.

Is it possible to stop people from killing themselves? A psychological autopsy, which scrutinizes the final deeds of the dead and the testimony of their friends and family, seeks to answer that question.

In an all-out effort to counteract the country’s high suicide rate, in 1987 Finland carried out psychological autopsies of all 1,397 of the suicides that had occurred over the previous year. This led to a national campaign to prevent suicides, and the suicide rate, which had been 30.2 per 100,000 people in 1990, dropped 47.7% to 15.8 per 100,000 people by 2012.

This approach has also taken root in South Korea, which opened the Korea Psychological Autopsy Center (affiliated with the Ministry of Health and Welfare) in 2014. On Jan. 26, the center published the results of psychological autopsies of 121 South Koreans over the age of 20 who ended their lives over the past four years.

The police and mental health professionals did their best to convince more grieving families to take part, but few were willing.

“There’s still a strong social stigma about suicide, so grieving families often have to endure that grief on their own, afraid of even letting people know that the suicide occurred,” said an official with the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

What is most evident from analyzing these psychological autopsies is that the suicide victims had been struggling with various life challenges, from the loss of a job to the loss of a loved one.

28.1% of the victims had faced a suicide, either successful or attempted, by a family member before. 54.5% had been out of a job for at least three months before their suicide, and 73.6% were dealing with job stress, whether this meant losing their job or moving to a new one. 69.4% of the victims had been dealing with family stress, which could mean conflict with their family or sickness or death in the family. 46.3% were dealing with marital stress, which includes marital discord, separation, and divorce.

Before committing suicide, 93.4% of the victims who received psychological autopsies had shown warning signs. Talking about death directly (“My time will be up soon, so you’d better stay healthy.”), complaining about physical discomfort (“I’m having indigestion.”) and speaking longingly of the afterlife (“What do you think heaven is like?”) – all of these can indicate that someone is thinking about or intends to commit suicide.

In addition to verbal indications, these warning signs can also take the form of action: abrupt changes in sleeping patterns, appetite, or weight; attempts to “settle accounts,” such as selling assets and distributing the proceeds to family members; or extreme drinking or smoking. Sometimes, suicidal tendencies can make themselves known through emotions, such as unusual lethargy or abrupt weeping.

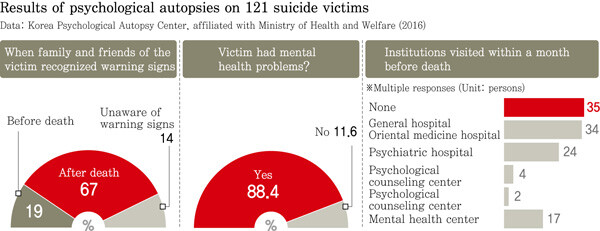

But in most cases, the true meaning of the warning signs was not recognized by family members until it was too late. Of the respondents to the survey, 67% said that they only understood the warning signs after the suicide occurred, while 14% said they were not sure whether there had been any warning signs.

While a majority of suicide victims (88.4%) had been struggling with mental disorders – including depression and addiction – less than 15% had been regularly receiving treatment. Some of the victims (25%) had visited a psychiatrist for counseling, but even more (28.1%) had only visited a Western or Asian clinic to address their poor sleep or indigestion. This underlines the importance of the “suicide prevention gatekeeper” program, which teaches people how to recognize the warning signs of suicide.

“Over the past three years, about 165,000 police, teachers and soldiers have completed the gatekeeper training program. In the future, we’re going to gradually expand the program into other fields as well,” said Cha Sun-kyung, director of mental health policy for the Ministry of Health and Welfare. “Based on the results of the psychological autopsies, we’re planning to release comprehensive measures for improving mental health, including the establishment of an early detection system for mental disease, in the middle of February.”

As of 2013, the South Korean suicide rate was 28.5 per 100,000 people – the highest rate of any country in the OECD for the eleventh year in a row.

By Um Ji-won, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8917132552387962.jpg) [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces![[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8317132536568958.jpg) [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

- [Guest essay] At only 26, I’ve seen 4 wars in my home of Gaza

- [Column] Syngman Rhee’s bloody legacy in Jeju

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 2[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test

- 3[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- 4[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- 5‘National emergency’: Why Korean voters handed 192 seats to opposition parties

- 6Faith the power of memory: Why these teens carry yellow ribbons for Sewol

- 7US grants Samsung up to $6.4B in subsidies for its chip investments there

- 8[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- 9[Photo] Cho Kuk and company march on prosecutors’ office for probe into first lady

- 10Exchange rate, oil prices, inflation: Can Korea overcome an economic triple whammy?