hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Seeking info, Hankyoreh reporters put on an unhappy merry-go-round by the NIS

Nine reporters on the Hankyoreh’s 24-hour metro desk separately asked their telephone companies to inform them if government institutions had requested their telecommunications data.

As of Mar. 10, three reporters - Park Tae-woo, Bang Jun-ho and Lee Jung-ae - had received confirmation from their service providers that their data had been provided to the government. The three reporters learned that their data had been provided between one and five times over the past year to the National Intelligence Service (NIS), the prosecutors and the police.

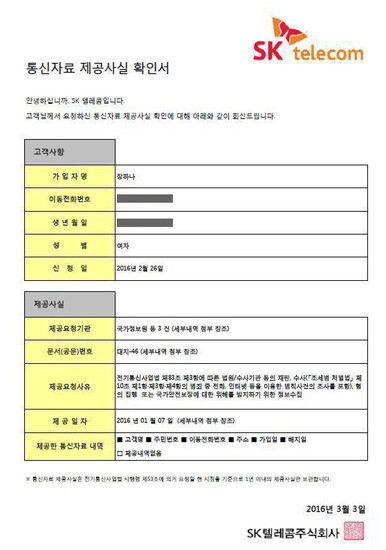

This was the same method that Rep. Jang Ha-na, a lawmaker with the Minjoo Party of Korea, used to determine that the NIS and the prosecutors had viewed her telecommunications data. Just two hours after she contacted the NIS about this, she received an official response from the agency.

“We were looking into the identity of the individual to whose phone number a text message had been sent by an individual under investigation for violating the National Security Law. Since Jang was not a suspect, we excluded her from our investigation,” the NIS said in his statement.

But would the NIS bother to provide this kind of explanation to someone who is not a lawmaker or a newspaper reporter?

The three Hankyoreh reporters who had learned that their data had been provided to the government contacted the NIS, the prosecutors and the police, respectively - pretending to be not reporters - to find out why those agencies had wanted their data. But in the case of all three reporters, an entire day went by without them learning why. The events are detailed below.

“In order to protect your personal information. . .”

On the afternoon of Mar. 10, reporter Bang Jun-ho‘s final hope was the automated answering service at KT, one of South Korea’s major telecom companies.

Bang had been informed by KT that it had provided his telecommunications data to the Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency on Dec. 2, 2015. On Thursday morning, he called the police agency in order to find out why it had requested his data.

While Bang tried calling both the main line and the public complaint line, the employees who fielded his calls did not even know what department he needed to contact to find out why the police had wanted his data. The public complaint office randomly patched his call through to the violent crimes department.

Poring over the website of the Korean National Police, Bang eventually learned of the existence of an officer in charge of “information protection.” But when he called, he was told that this officer only dealt with protecting the police‘s internal information.

The answer he received to each of his four phone calls to the police was that there is no separate department responsible for requests for telecommunications data. He would have to contact his service provider, the police said, if he wanted to find out the details about which department had made the request.

But the customer service representative at KT apologetically explained that KT did not have access to any other information than the fact that the organization that had requested his data was the Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency.

Pretty much the same thing happened to Lee Jung-ae. After confirming that the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office had accessed her telecommunications data from SK Telecom on Apr. 24, 2015, Lee called the prosecutors on the afternoon of Mar. 9. Her ride on the telephone merry-go-round - which took her to the public complaint office, to the warrant office, back to the public complaint office, to SKT, and back once more to the public complaint office - lasted until the afternoon of Mar. 10 without any answers.

An employee at the warrant office said that Lee would have to get a “permit number” from her service provider in order to determine which office at the prosecutors had requested the data, but SKT said that it only kept records of requests for data and that there was no way to determine the permit number.

“I don’t even know what department you need to call to figure this out,” an employee at the prosecutors’ public complaint office admitted.

No answer was forthcoming from the NIS, either. After finding out that his phone company had provided his telecommunications data to the NIS on Jan. 7 of this year, Park Tae-woo called the NIS‘s 111 Call Center on the morning of Mar. 10.

The person on the other end told Park that they would contact the department in charge without telling him which department that was. When the NIS still had not called him back that afternoon, he called the call center again only to be told to wait.

By Bang Jun-ho, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 6N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 7[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 10[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent