hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

More fears about NIS taking personal info of politicians, journalists and regular folks

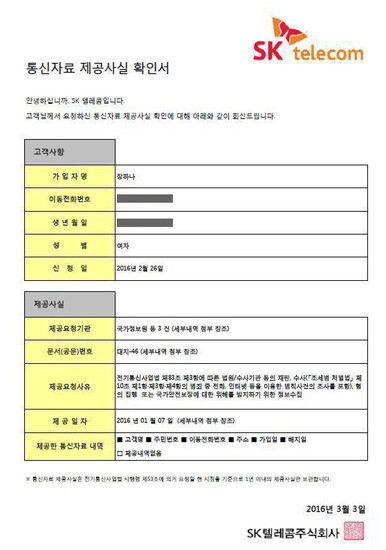

South Korean citizens are sharing fearful accounts of having their personal information taken amid ongoing revelations of bulk spying on the communications data of lawmakers, journalists, and even ordinary members of the public by the National Intelligence Service (NIS), prosecutors, police, and other intelligence and investigation organizations.

On Mar. 11, Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) secretary-general Lee Young-joo went public with a document confirming that personal data had been provided 28 times in the past year via her Facebook page. While receiving mobile communications company data sharing for its party officials, the Justice Party found that communications data for parliamentarian office aide Jeong Jin-hu and others had been passed along to police and the NIS.

Among the data in question were general details such as names, resident registration numbers, and addresses. The day before, the Supreme Court had ruled in an appeals trial for a suit by a 36-year-old surnamed Cha who demanded compensation from the online portal site Naver for violating its personal information protection obligations. Cha drew attention previously for posting a video showing figure skating champion Kim Yu-na apparently flinching from an attempted embrace by then-Culture Minister Yu In-chon. In its ruling, the court said the damage to Cha’s interests was relatively small because only general personal details had been provided to investigative bodies.

But information rights groups have voiced grave concerns, noting that resident registration numbers in particular can serve as “skeleton keys” unlocking other forms of sensitive personal information. Naver, for its part, said on Mar. 11 that it would not be providing communications data to investigation agencies without a warrant until a “social consensus” had been reached.

Police and other investigators have been able to find additional personal information from the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) and other public institutions using resident numbers from communications data.

“We have to confirm basic information before we can do additional investigating, so that’s why we receive communications data first,” explained a source with police.

“When people require additional information, we submit a request to other institutions for additional information,” the source added.

Indeed, the police previously drew fire for using communications company data to receive additional NHIS information about hospital treatment histories and conditions and the professions of family members while investigating the Korean Railway Workers’ Union (KRWU) leadership over its role in a 2013-14 strike. At the time, the police said the receipt of personal information from the NHIS and other public agencies was not problematic because of a Personal Information Protection Act provision granting exceptions in cases where such information was “necessary for investigation and the presentation and continuation of an indictment.” The KRWU and other have filed a Constitutional petition contending that the provision’s terms violate the vagueness doctrine.

The National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK), the Constitutional Court, and other state institutions have agreed in the past that resident registration numbers are “couplers” or “skeleton keys” for other types of personal information. While recommending improvements to the resident registration number system in 2014, the NHRCK described the numbers as “skeleton keys” and noted that their “connectivity as basic information linking to other forms of information” was a “chief characteristic.” In Dec. 2015, the Constitutional Court emphasized the numbers’ “coupling” aspect in a ruling finding the lack of regulations for changing numbers in the Resident Registration Act unconstitutional.

The NHRCK also issued a 2014 recommendation to the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning asking it to include communications data in the category of communications confirmation data and allow requests with a court permit. The ministry declined, citing “investigative agency fears that this could cause delays in criminal investigations and other hindrances to investigating.”

“Communications data aren’t just basic personal information. They can be used to allow investigative agencies access to sensitive personal information, and they need to be controlled,” said Chang Yeo-kyung, an activist with the Korean Progressive Network Center (Jinbonet).

By Bang Jun-ho, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 3Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 4[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 5Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 6[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 7Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 10‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis