hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

With Kakao Talk labor, the work day never ends

An individual surnamed Kim, 28, who works in customer service at a plastic surgery clinic in Seoul’s Gangnam district, has been fielding customers’ queries over the KakaoTalk, an instant messaging app, for more than three years.

Since KakaoTalk is used by nearly everyone in South Korea, the app is an attractive marketing platform for clinics. The majority of plastic surgery clinics have been expanding their customer service, answering questions over KakaoTalk not only from their patients but from prospective customers too.

Kim carries around two mobile phones - her personal phone and the work phone she was given by her manager.

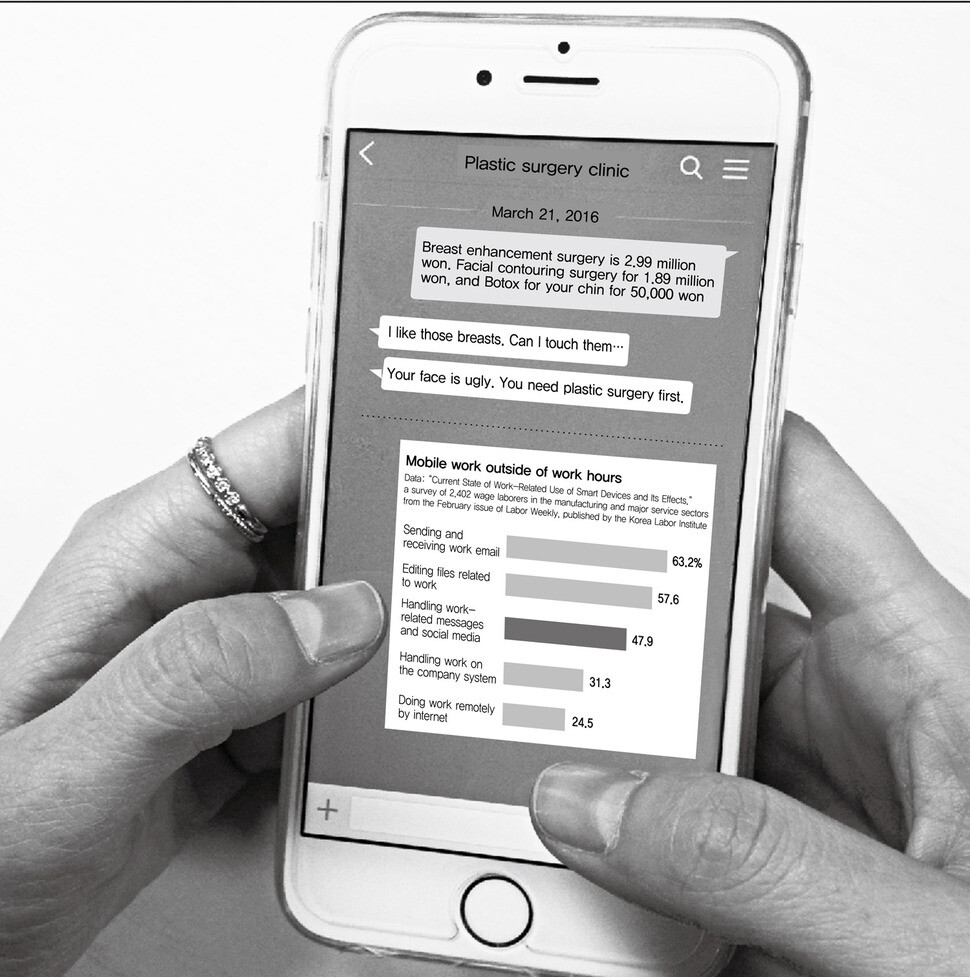

“Breast enhancement for 2.99 million won (US$2,575), facial contouring surgery for 1.89 million won, and Botox for your chin for 50,000 won. We’ve got the fastest special benefits, but only for our Plus Friends!”

When the clinic is running a promotion, Kim’s work doubles from the normal average of 30 to 40 KakaoTalk conversations a day. This is because Kim has to deal with a surge in people sending insulting or sexual messages or who complain about getting the message - even though the advertisement only goes out to people who are registered as the clinic‘s “Plus Friends” on KakaoTalk.

Clinic counselors has to be on call all the time

“When we launched a breast enhancement promotion, the ad featured a ‘before-and-after’ photo,” Kim said. “In one message I got, someone said they were a fan of breasts like that and asked if they could touch them. They also said they wanted to date a woman with that kind of breasts.”

When Kim uploaded a picture of her face as her profile picture, she was horrified to receive messages from people suggesting that she was the one who needed plastic surgery for her ugly face.

Kim is no longer surprised when people leave mundane questions late at night or in the early morning hours and then continue pestering her about why she is not answering. The work that she does is, in her words, “an extension of customer service at call centers, which is one of the best-known examples of an occupation involving emotional labor.”

But customer service representatives like Kim are hardly the only workers to complain of such difficulties. Regardless of the job, there is an increasing amount of work involving messengers like KakaoTalk and social media. South Koreans’ jobs are spawning a world of work inside their hands and personal computers.

It might be time for a basic discussion about work on Kakao Talk

Kim’s problems are not limited to when she is dealing with unpleasant “Plus Friends” on KakaoTalk. Since her manager keeps an eye on Kim’s KakaoTalk window, she has the feeling that her work is being watched at all times.

Kim’s manager tells her to respond to customers right away when they contact her on her work phone. And since Kim uses the company’s main ID and password, her manager can view her screen, too.

From time to time, Kim‘s manager reviews the messages Kim has sent and questions what she said and how long it took her to respond. These conversations typically end in Kim’s manager scolding her for failing to convince the customer to schedule a visit to the clinic.

“After work, I wasn‘t able to respond on KakaoTalk because I was watching a movie. The next day, I got in big trouble because a patient called the clinic saying that they didn’t get an answer. Since I’m not supposed to miss a message, I think I’m developing a complex about having to respond to messages right away in my personal life, too,” Kim said.

Even while Kim responds promptly to questions on KakaoTalk even when she is off the clock, she has never complained about her real working hours. She has never even thought about doing so.

Work worms its way into private time

In a survey about labor rights violations on mobile devices that the National Human Rights Commission of Korea carried out three years ago with 700 workers around the country, KakaoTalk and social media were identified as the IT technology that are used most frequently on the job (63% of respondents).

The more efficient the technology, the greater the chance that work will worm its way into private time and personal space. Indeed, these days it is rare to find an office worker who is not part of a group chatroom on KakaoTalk.

Even at mobile service providers, where employees often have to work on weekends because of the fierce competition to attract customers when new models of mobile phones are being released, the various departments are quick to create their own group chatrooms. Ideas for giving incentives to phone dealerships or discounts to customers and reports about current sales for each model at dealerships in a given region are posted to the chatrooms in real time.

“When I’m burying my head in the phone because of messages that get posted at all hours, it ruins the mood in my family on the weekend,” said one employee, who says he has to work at home at such times.

Mangers’ creeping control over their employees and their top-down instructions also tend to result in more dissatisfaction.

“My boss frequently gives work instructions over messenger when he‘s leaving for the day. I’m sure he‘s not intentionally trying to give us a hard time. Even so, when I get one of those messages I have to start thinking about work again, and I might as well be staying late to work. I daydream about escaping from the group chatroom,” said Song, 32, an office worker at one chaebol.

Even teachers get bugged by students and parents

Teachers also complain about these inconveniences.

“Even when I ask students at the beginning of the semester to send me a text message if they have a question, there are parents who contact me on KakaoTalk. There are even some parents who judge teachers based on their profile picture or their ID, which is a real source of stress,” said Kim, 33, an elementary school teacher.

“I get game-related messages from kids and work-related messages from parents all the time,” said an instructor at an English-language academy named Choi, 34.

An article titled “Current State of Work-Related Use of Smart Devices and Its Effects,” which ran in the February issue of Labor Weekly, published by the Korea Labor Institute, cited a survey of wage laborers in the manufacturing and major service sectors. Of the 2,402 workers surveyed, 1,688 (70.3%) said they used devices such as smartphones and tablet PCs to work on messenger, email or social media outside of working hours or on their days off.

On average, these people used smart devices more than 11 hours a week. On average, they used their smart devices on work-related matters around 86 minutes outside of their regular work hours on workdays and around 95 minutes on days off.

For many respondents (63.2%), such work consisted of sending and receiving email through their workplace email account.

In addition, 47.9% of respondents said that they had used messengers or social media to take care of work or to give instructions.

30% of workers said they had been encouraged to use their smart devices to take care of work-related matters outside of work hours or on their days off.

Respondents who said their working hours had increased because of smart device usage outnumbered those who said their working hours had decreased by a margin of two to one.

“When smart devices are used more for work, and particularly when smart devices are used for work purposes outside of working hours, there was a tendency for their negative effect to double,” said Lee Kyung-hee, an analyst at the Korea Labor Institute.

By law, pay for overtime and holiday work, must be 1.5 times the regular rate. But in that case, what should be done about always-on-call work, such as time spent on KakaoTalk? And what should be done about work-related health issues such as psychological stress?

Despite the rapid changes in the work environment in South Korea - often described as an IT powerhouse - there is virtually no discussion of the relationship between work and social media and messengers. Systems, culture and perceptions are failing to keep up with the march of technology, experts say.

Before tackling the question of compensation, experts say we ought to look at KakaoTalk labor as a human rights issue.

“Making collective agreements and receiving compensation at individual companies only addresses the symptoms. The important thing is to begin with the attitude that KakaoTalk labor is a human rights issue,” said Kim Jong-jin, a researcher at the Korea Labour and Society Institute.

“We need discussion in the government and guidelines about whether it’s appropriate for employees to be given instructions outside of work and, if not, what society can do to reduce this,” Kim said.

In Germany, France and elsewhere, collective agreements set rules for mobile phone and email use

A number of countries are already moving closer to a social consensus about labor involving smart devices.

According to a paper titled “Labor Law Controversies and Problems Related to the Work-Related Use of Smart Devices Outside of Working Hours,” by Kim Gi-seon, an assistant analyst at the Korea Labor Institute, which ran in the February issue of Labor Monthly, collective agreements are being used in Europe to enforce regulations about the work-related use of mobile phones and email.

Germany’s clear regulation explicitly bans companies from contacting employees about work by calling them on their mobile phones or sending them text messages or emails outside of their working hours.

In France, workers have also reached an agreement that prohibits companies from ever sending emails between 6 pm and 9 am.

In 2012, IG Metall, the German metalworkers’ union proposed the passage of anti-stress legislation to protect workers from the psychological risks associated with work.

Individual companies have also made a variety of responses to the issue.

Volkswagen has developed technology that prevents workers from being contacted about work-related matters during their time off. Half an hour after work is over, the email server for work smartphones goes off, and it does not come back online until half an hour before work resumes the following day.

This technological restriction does not apply to senior managers who often have to make urgent decisions and deal with crises or to those who are not covered by the collective agreement. In addition, the technology does not block messengers or phone calls.

At the request of employees, Daimler will automatically delete pending emails for all employees who are on vacation or who have been absent for five days or more. Anyone who sends an email at such time receives a response saying that the recipient is unavailable along with contact information for the person who is covering for them.

By Choi Woo-ri, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0415/7517131654952438.jpg) [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics![[Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0412/1017129080945463.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

[Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

- [Guest essay] At only 26, I’ve seen 4 wars in my home of Gaza

- [Column] Syngman Rhee’s bloody legacy in Jeju

- [Editorial] Yoon addresses nation, but not problems that plague it

- [Column] Can Yoon and Han stomach humble pie?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- 2[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test

- 3[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 4‘National emergency’: Why Korean voters handed 192 seats to opposition parties

- 5[Photo] Cho Kuk and company march on prosecutors’ office for probe into first lady

- 6[Column] A third war mustn’t be allowed

- 7[Editorial] New KBS chief is racing to deliver Yoon a pro-administration network

- 8[Editorial] S. Korea should take a note from US-China tactical compromise

- 9[Column] Down with the so-called social ladder

- 10Exchange rate, oil prices, inflation: Can Korea overcome an economic triple whammy?