hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] Two workers spend Labor Day in a “sky prison”

May 1 marked the 126th anniversary of International Workers’ Day. Children’s Day was scheduled four days later, Parents’ Day three days after that. Some people will be spending happy moments with their family for the holidays; others are fretting over not being able to get off work. Then there are two other men who greeted their 326th morning from atop a 10-meter-high billboard on the roof of a 13-story building in the heart of Seoul: Choi Jeong-myeong and Han Gyu-hyeop, employees of an in-house subcontractor at Kia Motors’ Hwaseong plant.

Choi, 46, and Han, 42, first climbed the billboard on top of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) building in Seoul’s Central district on June 11 of the last year to demand that illegally hired irregular workers at the plant be converted to full-time status. In Sept. 2014, they had won a ruling from Seoul Central District Court that confirmed their status as workers and deemed Kia Motors’ in-house subcontractor hiring practices illegal. In response, the company announced in May of last year that it planned to hire 465 new workers rather than converting its in-house subcontractor employees to full-time status - prompting Choi and Han to launch their protest.

In July 2010, the Supreme Court ruled that Choi Byeong-seung, a worker for an in-house subcontractor at Hyundai Motor Company, had been an illegal temp worker. And in February of last year, the Supreme Court ruled again that Kim Jun-gyu and three other people who had been working for a subcontractor at Hyundai Motor’s Asan Factory when they were fired had actually been regular workers at Hyundai Motor.Despite this, Hyundai and Kia have responded to requests to convert Choi and the other in-house subcontractor workers at Kia Motors to regular employees with plans to appeal the case once again.

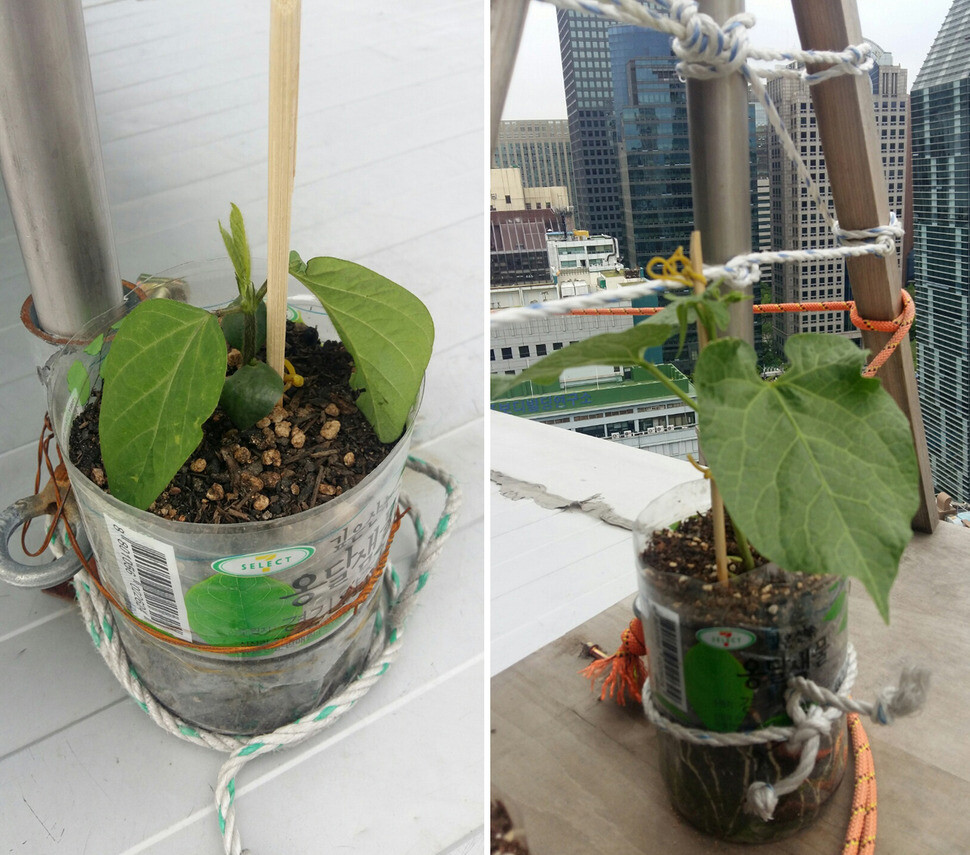

Atop the billboard, which is 20 meters long and just wide enough for two to sit down, the two workers are continuing their aerial protest with no end in sight.

On Apr. 30, the Hankyoreh conducted a telephone interview with Choi and Han. The two workers are ordinary men - heads of households, fathers of children - who worked hard to make cars while the management said they were all one family. In this interview, we will do our best to convey what Choi and Han said in all of its rawness, and upload it to coincide with Labor Day.

Choi Jeong-myeong was working for an in-house subcontractor at the Hwaseong Factory of Kia Motors, with a son in the sixth grade and a daughter in the first grade of elementary school. If he had not been fired 60 days into his aerial protest, this year would have been his tenth on the job.

Choi has been unable to tell his son, who is especially fond of him, that he is in the middle of an aerial protest, for fear that it will come as a shock. Choi has only told his son that he is working somewhere far away and that he cannot come home for a while. Choi promised his daughter, who started elementary school this year, that he would return when the flowers bloomed in the spring, but he was not able to keep his promise.

Hankyoreh (Hani): As of today, how many days has the protest been going?

Choi (Choi): 325 days.

Hani: Since you went up in June of last year, you’ve experienced all four seasons up there.

Choi: Actually, we didn’t think it would last so long. Every day seems to crawl, but next month will be one year, so I guess time has really flown by. It just feels like we’re in the middle of a really long dream. I’ve gotten used to my fear of heights, now. Even though I’ve adapted to the environment, it still doesn’t feel real. When I wake up in the morning, I feel like I’m dreaming.

Hani: What has been your toughest experience?

Choi: The fact is that while the heat and cold are really tough, personally the hardest thing was the humiliation my family had to undergo. After we came up here, they cut off the food and water. They didn’t even let them go up on the roof.

My wife demanded to send us some water and said otherwise we would die, the president of the advertising company said they would let us come down when we were dead. We have that on video. It would have been better not to watch it, but I did anyway and it really tore me up.

We already expected the worst when we came up here, but it really hurt to see my wife getting treated so badly when they went to the company out of desperation. The heat and cold have been tough, but it really hurt to think that my family was having a hard time, too.

Hani: Now that you bring up your family, let me ask this question. We were hoping to get a video message from you before Children’s Day [May 5] and Parents’ Day [May 8], but for a number of reasons that didn’t happen. What message would you like to give them?

Choi: I actually feel really sorry for my family. When I told my wife the day before coming up here that I was going to join the protest, she just stared at me without saying anything. But I could tell from her expression that she wanted to know why it had to be me when there were other people who could go. When I told her that someone had to do it and that it ought to be someone who had made up their mind, she accepted it calmly. After that, she asked me to promise that I would come back in good health.

We have our own problems up here, but my wife has plenty of challenges taking care of the kids, and she probably gets upset and worried when she hears what’s going on up here. I guess that things must be really terrible for her too. But I’m so grateful that she never lets on and always puts up with everything like a champ. Whenever I‘m having a really hard time, it helps me to think of my family and my kids.

Hani: I heard that you have a little girl.

Choi: My daughter is eight years old and started elementary school this year. She’s the youngest, and my son is in sixth grade. Usually boys aren‘t so fond of their dads, but my son really loves me. That’s why I haven’t told him that I’m doing this protest. I’m afraid that it would shock him.

Later when he’s grown up, he‘ll be able to decide about his values and convictions. For now, though, I figure that he would get emotional and take it the wrong way, so I haven’t told him. But he seems to have figured out that something is up with my work. Based on how my wife sounds when she’s talking to me on the phone, he must think that I’m working somewhere far away and that I‘m having a hard time in a really bad situation.

There’s this saying that you shouldn‘t talk about life with someone who hasn’t raised a daughter. After being apart for so long from my lovely little girl who I used to carry around all the time, I miss her so much. I promised her that I would be back when the flowers bloom in the spring, and I feel bad for not keeping that promise. I feel bad that I couldn‘t be at the ceremony at the beginning of the school year. [. . .] Even so, she’s learning how to read and write as she promised. I’m grateful, and I’m proud of her.

My son is starting to grow up, and he sometimes thinks he’s old enough that he doesn’t need to obey his mother. When I come down from here, I want to make up for the time I couldn’t spend with him by going hiking and going fishing. I’m going to do everything I promised -- go on a camping trip with the family of one of his friends from the next neighborhood and cook some barbecue. I wish I could tell my son to listen to his mother and to wait for me.

Hani: A lot of people are curious about how your health is holding up.

Choi: The truth is we‘re not in good health. This isn’t a situation where we could be healthy. I didn’t have any trouble with my blood pressure before, but I’ve started taking some medicine since coming up here. Han Gyu-hyeop - the guy who is up here with me - has severely high blood pressure, and as the protest has dragged on, they’ve gradually upped his prescription.

When a doctor came up here a while ago, he said that Han’s blood sugar level had gone up, too. If there’s no improvement, he’ll have to get a prescription to regulate his blood sugar, too. The fact is, we have aches and pains all over.

Hani: I read the interview that you did last summer on the 29th day of the protest. You said that you were in a “sky prison” and that this was “worse than actually being in prison.” You mentioned Cha Gwang-ho, who at the time was in the 408th day of an aerial protest [over the shutdown of the Star Chemical factory in Gumi, North Gyeongsang Province], and said that “it must be an incredible struggle between his strength of willpower and himself.” How does it feel now that you’ve been up here almost the same amount of time?

Choi: I think that anyone who has actually experienced an aerial protest will know what I was saying. You’ve locked yourself up in prison, and because of the isolation you can‘t feel comfortable either in body or soul. The mood swings become really severe, too.

We’ve taken medication since coming up here, too. We make a big effort to maintain our mental health and to find peace. We make a lot of conscious efforts to read books, meditate and control our emotions. But since we‘ve been up here so long, we’re starting to see symptoms like feelings of depression and pent-up frustration.

When you’re frustrated about something, you want to talk about it, but we’re in a position where we have to stay calm and smile as we talk. That’s how I blow off steam a lot with Han Gyu-hyeop, who is up here with me.

Hani: You’ve expressed your views by hanging up a huge sign that says, “Chung Mong-koo should take responsibility for Kia Motors turning its irregular workers into regular workers.” Is there anything you would like to say to the company directly?

Choi: I wish common sense was more prevalent in this world. By common sense, I mean what people generally think and the standards they use to draw conclusions, and I mean abiding by our social and legal system.

But I feel that things are really unfair. Workers are treated so harshly whenever they violate the Assembly and Demonstration Act or the Labor Standards Act. They get laid off, and the law is strictly applied if they complain at all about unfairness.

But Hyundai and Kia have been illegally using temp workers for decades now. The courts have made the same rulings on several occasions, but the companies aren’t budging. These are serious crimes against society, but they aren’t being prosecuted for those crimes. The prosecutors may have called [Hyundai and Kia] Chairman Chung Mong-koo in for questioning one time, and the courts may have made one ruling. Given these circumstances, shouldn’t the Labor Ministry be providing some special oversight on this issue?

Right now, while we are in this aerial protest, the court keeps agreeing to the company’s requests to postpone the sentencing. It took the district court three years to make its ruling. Now the appeals court has pushed back the date of the sentencing for the third time. It‘s really unfair.

So as we said in the banner we put up, we think that Chairman Chung Mong-koo is the person who can actually address this problem of illegal temp workers. If the company really want to become a global automaker, then this kind of inhumane approach to corporate ethics has to be discarded.

Selling a lot of cars isn’t enough to become a global company. I hope that they’ll develop a mature social ethic. Even chaebol aren’t above the law. I sincerely hope that they’ll hurry up and acknowledge their illegal use of temp workers and that they’ll hire on the irregular workers at in-house subcontractors as regular workers.

Han is less worried about his two older children, who are adults and understand what is going on. But he keeps thinking about his youngest daughter, just six years old, who asks about her daddy every day.

Hani: Did you think that it would take this long?

Han Gyu-hyeop (Han): I knew that this wouldn’t be easy, but I had no idea that society would be so apathetic. When we came up here, we had been expecting that it would take a while. But the company keeps dragging things out since no one is doing anything to stop its illegal activity. That’s what is most frustrating.

Hani: Is there anything you’d like to say to the company directly as Choi did?

Han: Money isn’t everything in this world. You shouldn‘t look at and judge everything through the single lens of money. Every day at the company, we were told that everyone was part of the same family and were urged to work together and do our best.

If you make a mistake, all you have to do is admit you were wrong and make it right. The problem is that the company isn’t admitting its wrongdoing and is trying to use money and power to get out of this. But they wouldn‘t do that if we were really family.

I wish they would just stop already. If they asked people to work for them, they ought to pay them a fair wage, and that’s what the courts have been ruling, too. I wish that Chairman Chung Mong-koo would act the way someone ought to act in his social position as the leader of a chaebol.

Hani: Let me ask you the same question [I posed to Choi]. What would you like to say to your family?

Han: Since my oldest kids are adults, they know what’s up, and I’ve been sharing things with them. My eldest son is about to do his military service, and my older daughter got a job not long ago. My youngest daughter is six years old.

I don’t have much to say to my family, because I feel guilty. With me gone, there’s no one to keep food on the table. Both Choi and I are the breadwinners in our families. We’re the heads of our families, and we’re asking our families to make all the sacrifices while we‘re up here with plenty to eat. I knew that coming up here would be bad for my health.

Since we’ve been staying up here for so long, it hurts me to think of how my family is suffering. My wife hasn’t complained one time so far, and she listens to me when I tell her the family should stick together and do whatever it takes to make it through the tough times.

It makes me feel twice as guilty when she says we should stay up here until we win and that I just need to stay healthy. If she hated me or complained, I would probably be able to relax a little, but the fact that she doesn’t makes me feel even worse.

As a father, I feel sorry for not being able to provide my kids with the simple feeling of being in a normal family.

The interview ended with some gallows humor. “At least I can still walk,” Han said, with his brave laughter echoing from the receiver of the phone.When will these two workers be able to come down from their “sky prison”?

By Kim Ji-eun, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 2[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 3Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 4Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 5Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 6Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 7New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 8[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 9[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 10[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue