hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] In embracing North Korea, China sending the South a message

The escalation continues. The Chinese government is using the ASEAN Regional Forum in Laos and a series of foreign ministers’ meetings to openly voice unhappiness over the South Korean and US government’s decision to deploy a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system with US Forces Korea. It’s a dangerous moment, where failure to resolve the THAAD conflict quickly could result in a typhoon that engulfs South Korea-China relations.

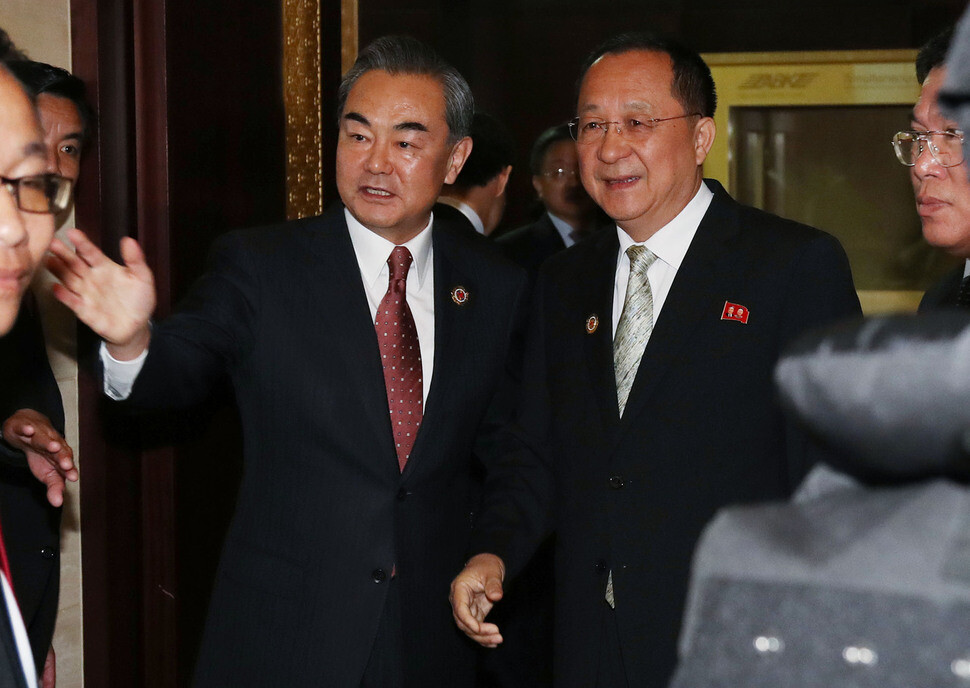

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi held bilateral talks lasting a little over hour on July 25 with his North Korean counterpart Ri Yong-ho at the National Convention Center in Vientiane. Before their talks, a public relations officer for the Chinese Foreign Ministry suggested that South Korean reporters cover them at the scene. It was an unprecedented move: Pyongyang and Beijing had never before opened up their bilateral meetings to South Korean journalists. Two South Korean pool reporters subsequently went to cover Wang and Ri’s introductory remarks.

The Chinese government’s plan appears intended to use a diplomatic show of embracing North Korea as a way of sending the South Korean public a message about Beijing’s unhappiness with the THAAD deployment. It also came as part of a series of similar measures from Beijing: Ri being seen off by the Chinese ambassador to Pyongyang on July 23, Ri and Wang taking the same airplane to Laos on July 24, the North Korean and Chinese delegations choosing the same hotel that day, and now the July 25 decision to open the bilateral foreign ministers’ talks to South Korean reporters. Taken together, they strongly suggest a carefully planned diplomatic maneuver targeting Seoul. At one point, Wang even provided a tender moment, appearing at the front of the meeting room with his hand on Ri’s back. His message to Ri, however, was a reiteration of Beijing’s standard “three principles” for denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

“China firmly supports denuclearization of the [Korean] peninsula, maintaining peace and stability, and solving problems through dialogue. This basic policy will not change,” he declared.

The warmth stood in stark contrast to the decidedly chilly attitude shown late the night before in talks with South Korean Minister of Foreign Affairs Yun Byung-se. Yun, who had set the bilateral meeting with Wang as the last item on his agenda for July 24, attempted what a Ministry of Foreign Affairs source called “significant ‘persuasion diplomacy’ without concern for the time.” But Wang proceeded to drop several bombs for South Korean reporters, while limiting the meeting time to less than an hour instead of the ninety minutes of more hoped for by Seoul.

In his meeting with Yun, Wang declared it “dismaying” that “South Korea’s recent actions have hurt mutual trust” and said he wanted to “hear what practical actions South Korea plans to take to preserve our relationship.” His remarks are expected to spark controversy, as they went beyond simple opposition to the USFK THAAD announcement to openly call for corrective action with a halt to the deployment. It was an extension of China’s escalation of its strongly worded warnings of action in response, which went from a Foreign Ministry spokesperson expressing “strong dissatisfaction” on the day of South Korea and the US’s announcement of the deployment decision on July 8 to another spokesperson’s statement on July 11 warning that China could “take corresponding measures to protect its interests” and a third on July 13 threatening to “resolutely take the necessary measures to protect China’s peace and stability.” Wang‘s statement asking to hear “what practical actions South Korea plans to take” could be seen as a final warning to Seoul before Beijing goes ahead with its “necessary measures” - applying diplomatic pressure on South Korea to choose between abandoning THAAD or letting its relationship with China crumble.

Particularly noteworthy in that sense were Wang’s remarks to Yun noting that South Korea and China have “entered the era of ten million human exchanges” and stressing that the cooperation “is bringing benefits to people in both countries and will continue doing so in the future.” While it could be read as a basic comment about not allowing the USFK THAAD controversy to hurt bilateral cooperation, it also could come across as a warning that Seoul’s decision to go ahead with the THAAD deployment could have a negative impact on economic cooperation, including the over ten million human exchanges each year.

Indeed, South Korea and China had a total of 10,420,000 human exchanges last year, of which 5,980,000, or 57%, consisted of Chinese visitors to South Korea. Bilateral trade for 2015 stood at US$227.4 billion, more than South Korea’s trade with the US, Japan, and the European Union put together. Not only is China far and away South Korea‘s biggest trade partner, but South Korea also recorded a surplus of US$46.9 billion with it last year alone. If Beijing did decide to place tangible and intangible economic pressure - by limiting South Korean tourist visits to South Korea, for example - the impact on the South Korean economy would be far from simple.

The problem is that despite the Chinese government’s stern expressions of unhappiness and aggressive pressure tactics, any common ground for resolving the two sides‘ differences on the USFK THAAD issue appears unlikely to be found for the moment. In response to Wang’s decision to forgo diplomatic rhetoric in favor of blunt pressure tactics, Yun stressed that the North Korean nuclear and missile threat was a “matter of the state and people‘s survival” and said the deployment decision was “something a responsible government should do as a self-defensive measure.” Rather than suggesting Seoul might offer the kind of concessions needed for compromise, he merely parroted the same official stance already voiced numerous times by President Park Geun-hye at National Security Council meetings and other settings.

The overt pressure on Seoul and embracing of Pyongyang by Beijing reads as a response to the US and Japan’s pressure against China over a dispute in the South China Sea and the aggressive move made by South Korea and the US with their USFK THAAD decision. It singles not only inevitable cracks in international coordination against North Korea over its nuclear and missile issues - a matter of major emphasis for Seoul and Washington - but also an increasingly complex situation in Northeast Asia. It could also bode ill for the South Korean economy as it struggles to escape low growth conditions.

By Lee Je-hun, staff reporter in Vientiane

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 5US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 6[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10More South Koreans, particularly the young, are leaving their religions