hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] A documentary made by “the land and sky of Korea”

“I’m so glad that a Japanese person took a risk and managed to accomplish something that no Korean has dared to do. Let’s give him a big hand,” said Han Seung-heon, a lawyer and former chairman of South Korea’s Board of Audit and Inspection. It was the afternoon of Sep. 24, and Han was speaking at a restaurant in the Insa neighborhood of Seoul during a final meeting for those who had supported the production of the documentary “Donghak Peasant Revolution: Chili Peppers and Rifles.” Han’s remarks were followed by a round of applause for Kenji Maeda, 81, the director of this documentary.

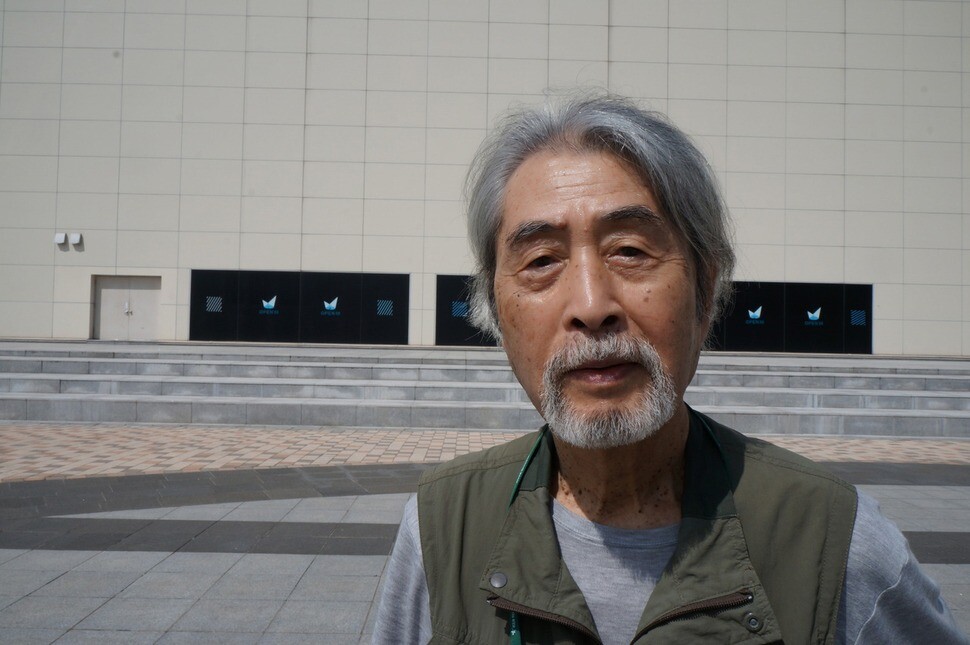

This documentary was selected for the special focus at the DMZ International Documentary Film Festival, and it will be screened at the Baekseok Megabox theater in Goyang, Gyeonggi Province, on Sep. 27, following a previous screening on Sep. 25. A Hankyoreh reporter met Maeda, the director, at the DMZ Square, near Baekseok Station in Goyang, on Sep. 25.

The film crisscrosses South Korea in search of traces of Choi Je-woo, the founder of the Donghak Movement, and the Donghak Peasant Army. The sad voices of the descendants of the peasant soldiers show just how cruelly and systematically the Japanese troops slaughtered the peasant army. Experts on the subject are also interviewed to explain why the uprising should be called a revolution.

“This movie wasn’t made by me. It was made by the land and sky of Korea, by the wind and by the voices of people heard inside it,” Maeda said.

During a briefing about the production of the documentary three years ago, Maeda said that the First Sino-Japanese War (1894) and the Russo-Japanese War (1895) that were started by Japan, Japan’s colonization of Korea and the Pacific War were all rooted in the Donghak Peasant Revolution. The violent ideology that justified the slaughter of Korean peasants at the time led to the Pacific War, he said.

Maeda brought up the story of Soroku Kawakami (1849-1899). As logistics commander for Japan’s Imperial General Headquarters in Hiroshima at the time of the Donghak Revolution, Kawakami was the one who gave orders for all of the Korean peasant soldiers to be slaughtered.

“I tried to meet with Kawakami’s descendants who are living in Tokyo to ask if they were aware of what their ancestor had done. But they refused [my request for an interview]. I was able to view the document containing Kawakami’s order at the Defense Ministry, but they wouldn’t let me take any pictures or video,” he said.

Noting that even South Korean intellectuals hardly know anything about Kawakami, who was in charge of military affairs during Japan’s invasion of Korea, Maeda said that they ought to “feel responsible” for their apathy.

Maeda’s original title for the film had been “Donghak Peasant Revolution: Under the Persimmon Tree.” The phrase “under the persimmon tree” was replaced with “chili peppers and rifles.” The persimmon tree that stood at the Malmok Market in Jeongeup at the time of the Gobu Uprising was a meeting place and a resting spot for the peasant army.

“We’re seeing the events of 122 years ago play out again in Japan today”

Maeda says that he changed the title because of a memorable story he heard from a chili pepper farmer whom he met on Hajo Island, Jindo County, South Jeolla Province. “The peasant soldiers who were being chased by the government troops and Japanese troops passed through Jindo and took shelter in the surrounding islands. The descendant of the peasant soldiers that I met on Hajo Island, whose surname is Park, said he has hidden his ancestry out of fear of discrimination,” Maeda said. Park told Maeda that people called his family “the cudgel Parks” behind his back.

“I get the impression that we’re seeing the events of 122 years ago play out again in Japan today. I hope that this documentary will be screened throughout Japan,” Maeda said. To start with, the film will be shown five times at the Korean YMCA in Tokyo on Oct. 10 and 11.

“Japanese elementary school, middle school and high school textbooks do not cover the Donghak Revolution at all. This film will give the Japanese another opportunity to reflect on the cruelty of war,” he said.

Maeda had originally meant to complete the film the year before last, to coincide with the 120th anniversary of the Donghak Revolution, but he was two years late. The biggest obstacle was the cost of production.

“I was able to raise 12 million yen of my 13.3 million yen (US$131,980) budget with the help of the members of a South Korean support group. [Because I was low on funds,] I had to sell my prized Korean pottery for 350,000 yen when I could have gotten 8 million yen for them. I went into debt, too,” he said.

Supporters in South Korea also raised 33.9 million won through Daum Kakao’s Story Funding, with 1,549 people taking part.

Maeda was unable to do filming in North Korea as he had hoped. “Large numbers of the [defeated] peasant soldiers fled north. I asked some senior officials at Chongryon to help me contact their descendants, but my request was denied,” he said.

Both Chongryon and Mindan refused to work with Maeda during his filming of the documentary, probably “because they were uncomfortable with an activity that was opposed to the Japanese government,” he said.

Chongryon (the General Association of Korean Residents) and Mindan (Korean Residents Union in Japan) are two Japan-based organizations that are affiliated with North Korea and South Korea, respectively.

Maeda’s inspiration for making the documentary about the Donghak Revolution is largely due to his connection with [South Korean] director Shin Sang-ok (1926-2006).

“In 2001, I visited most of the sites of the Donghak Revolution with Shin. Shin tried to raise 40 billion won to make a cinematic version of the Donghak Revolution, but he wasn’t able to raise enough money,” he said.

After Shin passed away, Maeda made up his mind to make a documentary himself with a budget of 30 million yen.

Experiences making two documentaries related to Korea and Japan

Maeda was born in Kyoto and spent his early years in Osaka. “When I was in the third and fourth grade of elementary school, I fought in the war as a student soldier. I saw countless people killed. At the end of the war, I was swimming in a pond with my older brother when we were almost killed by an American fighter. To this day I vividly remember the American soldiers shooting at kids like it was some kind of joke,” he said.

When asked about the possibility of war, Maeda responded as follows: “Right now we’re at a stage that is similar to preparing to go to war. It’s a prologue, so to speak. I don’t know whether it will be 10 years or 50 years [when war breaks out]. This is the age of nuclear war. I don‘t think that there will be a big war, but I do feel a little anxious.”

In order to prevent war, Maeda said, “it’s important for the public to be opposed to the war.” Making sure that more people share that view is particularly important, and he views his documentary as being part of such an effort.

In the introduction to the documentary, there is a shot of Han, the lawyer, paying his respects at the grave of former president Kim Dae-jung (in office 1998-2003). “One important objective of this film is democratization. I think that South Korea needs to become democratized once more. That’s why I didn’t omit the scene of Han paying his respects despite his misgivings,” Maeda said.

Maeda received the Jeweled Crown of the Order of Cultural Merit from the South Korean government for directing “The Painful Tales of Millions,” a 2000 documentary based on the testimony of Koreans forced into sexual slavery and other kinds of labor. In 2009, he directed “Invaders under the Moon,” a documentary about the Imjin War, a series of Japanese invasions of Korea at the end of the 16th century.

By Kang Sung-man, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 4Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 5Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 6Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 9[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 10Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report