hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Single person households rise to most common form of household in South Korea

Kim Gyeong-sik (49, not his real name) lives by himself in a motel in the Seongdong District of Seoul. Kim used to have a family: he was married and was raising two kids. But his transition from a four-person household to a single-person household occurred after his divorce in 2000. After losing his job, he turned to the bottle, and he began to fight with his wife more often. Eventually, they split up.

Kim gave up custody of his kids during the divorce, and today he has lost touch with his family. Since he started living alone, his income and housing have been unstable, and he has had a series of health problems. He made about 1.5 million won a month at an apparel factory, and he has moved around between government-subsidized apartments, flophouses and motels.

After Kim received an operation following a heart attack this March, the government ruled that he was unable to work and enrolled him in a program that provides basic livelihood benefits. When he gets better, he will have to start working again, but Kim is worried that it won’t be easy for him to find another decent job. Asked about the hardest part of living alone, Kim said that it was “loneliness.”

“When you’re on your own, you feel the saddest when you’re sick. That’s what I’ve been going through recently,” he said.

Last year, single-person households like Kim’s began to outnumber not only traditional four-person households but also two-person households, which had been on the rise increasing until five years ago. Single-person households are more vulnerable than multi-person households in a variety of areas including income, housing and health, analysts say. Given the steep increase in the number of middle-aged individuals who are entering the single-person household category after losing their job or getting divorced, there are concerns that these people may go on to suffer poverty in their old age.

A sharp increase in the number of middle-aged people living alone

Statistics Korea, which carries out a comprehensive population and housing study every five years, defines single-person households as households in which a single person makes a living, cooks, and sleeps alone. This concept expands upon the original academic definition of a single-person household, which is a household consisting of a person who has no spouse. This expanded definition includes not only those who live alone because they are unmarried, divorced or widowed but also those whose work only permits them to see their spouse on the weekends and so-called “goose fathers” (and mothers) who send their children and spouses overseas to study while they stay behind.

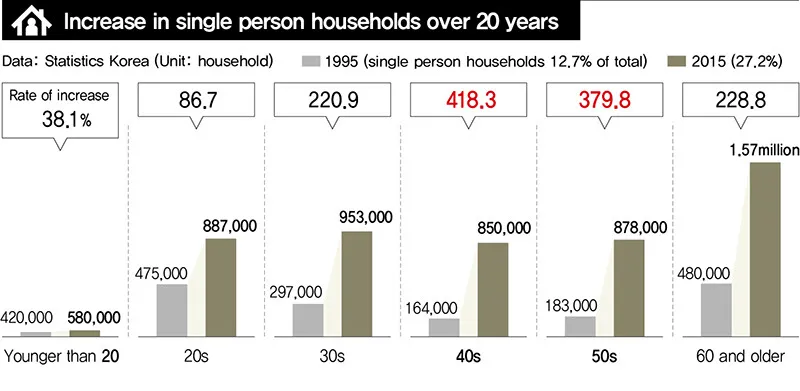

As of last year, there were 5.2 million single-person households in the country, amounting to 27.2% of the total 19.56 million households. The total number of households has increased by 51% since 1995 while the number of single-person households has increased by 216.9%. Essentially, single-person households are driving the increase in the total number of households.

When single-person households are categorized by marital status, the most common status was unmarried households, accounting for 44.5% of such households as of 2010. Other common types of marital status were widowed (29.2%) and divorced (13.4%), while in 12.9% of single-person households the person lived alone despite being married. Compared to the 2000 survey, the percentage of widowed single-person households has decreased while the percentage of divorced, married and unmarried households has increased.

For each generation, there were differences in how people came to live by themselves. Among young people, single-person households for the most part consist of unmarried individuals who have moved out of their parents’ house. In contrast, middle-aged people in single-person households were more likely to have started living on their own after splitting up with their spouse because of issues such as losing their job, getting divorced or educating their children. The elderly become part of single-person households for reasons that include being widowed, being divorced late in life and being separated from children who had looked after them. With increasing age, single-person households are more likely to represent an involuntary situation imposed by family breakup or bereavement rather than a voluntary decision.

In recent years, the rate of increase of middle-aged single-person households has been remarkably high. In the past, the elderly and people in their 20s made up an overwhelming share of single-person households. However, there were 1.73 million middle-aged single-person households last year, which was up nearly 400% from 1995 (when there were 347,000), making this age group the one that has increased the fastest among single-person households over the past two decades. The rapid increase among middle-aged single-person households can presumably be attributed to the increasing number of families broken up by divorce and to unmarried young people entering the ranks of the middle-aged.

Single-person households are more vulnerable than multi-person households

Despite the common perception that singles are living the high life, a variety of studies show that single-person households are more vulnerable than multi-person households. According to a report titled “Strategies for Countering New Social Dangers Resulting from the Increase of Single-Person Households” that KIHASA was commissioned to prepare last year by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, single-person households not only have a lower economic standing than multi-person households, but they are also worse off in terms of their housing type, residential environment and health level.

Researchers for KIHASA came to this conclusion after comparing and analyzing the disparity between single-person households and multi-person households by generation, including the young (20-39 years old), the middle-aged (40-64 years old) and the elderly (65 and older), based on data from the ninth year (2014) of the South Korean welfare panel.

In the case of young single-person households, it is estimated that there is considerable polarization inside the age group, given the ambivalent results found by comparing them with multi-person households. Single-person households receive a higher average yearly income (44.65 million won) than multi-person households (35.40 million won based on the household equivalence scale), but single-person households also have higher rates of working poverty and unemployment. This means that there are young people living alone who have well-paying jobs, but that there are also a considerable number of young people living alone who are in poorly paying jobs.

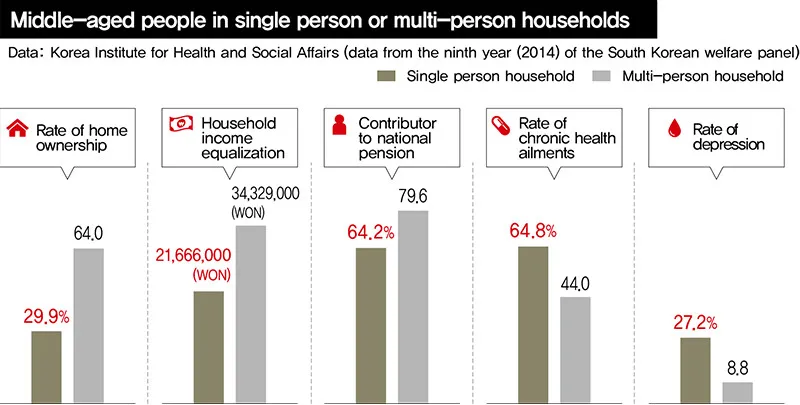

A bigger disparity between single-person households and multi-person households can be seen in the middle-aged and elderly age groups. Even among middle-aged single-person households, which are still more capable of working than the elderly, quality of life was lower than among multi-person households. The yearly income of middle-aged multi-person households was 34.33 million won (US$34,330), compared to 21.67 million won (US$19,780) for single-person households. While 64% of multi-person households owned a car, only 29.9% of single-person households did so.

The working-poor rate, defined as the percentage of poverty among people who have jobs, was 7.9% among multi-person households but 28.2% among single-person households. Aside from issues of income and housing, there were also higher rates of chronic illness, signs of depression and suicidal thoughts among middle-aged single-person households than among middle-aged multi-person households.

“The characteristics of middle-aged single-person households are similar to those of elderly single-person households. The only difference is that their dangers and problems are a little less severe than the elderly. In addition to elderly people who live by themselves, middle-aged single-person households are gaining prominence as a new vulnerable sector of society,” said Kang Eun-na, an analyst with KIHASA.

Kang noted that a substantial percentage of middle-aged people living by themselves find themselves in day labor and other unstable work situations after a layoff or divorce puts them in the single-person household category. This places them at risk of ending up destitute in their old age. Furthermore, since a low percentage of such individuals are enrolled in the national pension plan or in private pension plans, they are largely unprepared for retirement.

“Among single-person households, the major risks are found in unemployment and poor housing environment for the young; breakup of the family, unemployment and depression for the middle-aged; and poverty, disease and the risk of accidents for the elderly. Programs should be developed to provide single-person households with primary or supplemental support,” Kang said.

By Hwangbo Yon, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Asia Future Forum brings bright minds together to explore democracy’s future [Editorial] Asia Future Forum brings bright minds together to explore democracy’s future](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2025/1024/1317612945603513.jpg) [Editorial] Asia Future Forum brings bright minds together to explore democracy’s future

[Editorial] Asia Future Forum brings bright minds together to explore democracy’s future![[Column] Russia and China’s golden ticket to destabilizing the dollar [Column] Russia and China’s golden ticket to destabilizing the dollar](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2025/1023/2117612083961121.jpg) [Column] Russia and China’s golden ticket to destabilizing the dollar

[Column] Russia and China’s golden ticket to destabilizing the dollar- [Correspondent’s column] Martial law comes for the United States

- [Column] The end of the road for NewJeans, or a new beginning?

- [Editorial] Korea must prepare for rough road ahead with Japan

- [Editorial] Korea cannot afford to rush to a deal with the US

- [Column] Shared dilemmas at a historic turning point for Korea, Europe

- [Column] Halfway across the world, I’m cheering on Americans fighting for democracy

- [Column] How meritocracy turns into tyranny

- [Column] The real scandal of Korea’s ‘divorce of the century’

Most viewed articles

- 1Korea’s response to martial law crisis a model of 3 strategies for defending democracy, says Levitsk

- 2[Editorial] Asia Future Forum brings bright minds together to envision democracy’s future

- 3Real-life heroes of “A Taxi Driver” pass away without having reunited

- 4Xi and Trump bring their battle to Gyeongju

- 5[Interview] ‘AI is not really intelligent’: Ted Chiang on science and fiction in the LLM boom

- 6Pres. Park’s approval rating up to nearly 50% after inter-Korean agreement

- 7North Korea asserts its presence before Trump arrives in South Korea

- 8Lee says US tariff deal may not be finalized by next week’s APEC summit

- 9Korea, US will soon start negotiations on revising nuclear energy pact, says FM

- 10Former bodyguard’s dark tale of marriage to Samsung royalty