hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

33-year-old has vasectomy, as more young people give up on having children

Shin Ji-hoon, 33, went to the hospital for a vasectomy in February. An office worker, he is in his fourth year of marriage. Shin and his wife had given up on the idea of children for financial reasons, and he thought he needed a more reliable form of birth control. “I’m not very well off myself, and I figured that I would end up leaving my kids in an even worse position. After deciding not to have a child, I settled on a surefire way of eliminating the possibility of pregnancy,” he said.

Shin felt sorry about having had his wife get prescriptions for “morning after” pills. These days, he says, vasectomy often comes up in conversation with people he knows. “When I hang out with friends my age, we often have debates about whether it’s even possible to raise kids,” he said.

Vasectomies once symbolized the South Korean government’s policy of decreasing the birthrate. During the 1960s, the government covered the cost of vasectomies as part of its family planning program; in the 1970s, it gave men who had vasectomies an advantage in bidding for apartments.

But the government did an about-face when South Korea’s birthrate tanked. At the end of 2004, the government even eliminated coverage for vasectomies under national health insurance. But despite government policy, the story of this man in his 30s who rejected the idea of having children and decided to have a vasectomy reflects the harsh truth of South Korean society, in which people can’t have children even when they want to.

One of the factors that has been speeding up the “inverted population pyramid” in South Korean society is the fact that young people are getting married later and putting off childbirth or even writing it off altogether. The longer couples delay marriage and childbirth, the older women are when they give birth to their first child, which ultimately shortens their childbearing years. According to a study of demographic trends by Statistics Korea, the average age of women’s first childbirth increased from 26.2 years in 1993 to 31.2 years in 2015. During this same period, the total fertility rate sank from 1.65 to 1.24.

This isn’t because young people are selfish. Rather, it’s because the costs incurred at each stage of the life cycle (getting married, buying a house, having kids and educating them) are steadily increasing while the economic position of young people in their 20s and 30s is weakening across the board – in employment, income and housing. People in this age group are sometimes called the “sampo generation,” an abbreviation for a Korean phrase that means giving up three things – a career, marriage and kids. That’s why an increasing number of people argue that the government ought to be doing more to stabilize employment and housing for the younger generation, if it wants to combat the low birthrate.

The gap between hopes and reality

Shin planned on having kids after he got married, but life’s challenges changed his mind. At first he lived in Seoul, but gradually he was forced to move further and further into the suburbs. It was hard to save enough money to keep up with the key money, which increased at the end of each two-year contract, and so he took the rash step of taking out a key money loan. Now, 1.5 million won (US$1,300) each month goes to covering the interest and paying back the principal on the loan. Shin and his wife make a combined income of 4.5 million won (US$3,900) a month, but after covering their living expenses and giving their parents an allowance, they hardly have any money left over.

“If my wife got pregnant, I thought it would cost more than we could handle. It seemed like if we became parents we might not have enough money to give our kids what they want, so I felt it would be better just to not have any kids,” he said.

People like Shin who give up on having kids and who use birth control to stay childless can also be seen in statistics. A 2015 fact-finding study of national fertility and of family health and welfare by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) that surveyed 8,219 married women of childbearing age who were on birth control found that 30.1% of childless women in that group were taking birth control because they didn’t want to have children. Furthermore, 80.5% of the women in this group who already had a child were taking birth control because they didn’t want any more children. Among women who wanted to delay childbirth, economic reasons such as “inadequate income” were one of the major reasons for taking birth control.

Surveys like the one carried out by KIHASA also effectively show that there is a big gap between the ideal world and the real world in terms of how many children women want to have. When asked what their ideal number of children was, married women (11,009 women between the ages of 15 and 49) said 2.25 on average. But their expected number of children (the children they currently have plus the children they still plan to have) was 1.94, and their actual number of children was just 1.75.

This gap between hopes and reality was especially stark among younger married women. Rather than describing the young generation as being full of selfish people who are only interested in their own happiness, it may be more accurate right now to say that anxiety about the present and future are robbing them of the joy of having and raising children.

The birthrate varies with income levelAn analysis of childbirth statistics over the past 10 years by South Korea’s National Health Insurance Service shows that the third quintile of insurance enrollees based on their premiums (representing the middle class) accounted for the greatest percentage of childbirths (26.2%) in 2006, while the fourth quintile (high-income earners) made up the largest percentage (33.8%) last year. While the percentage of childbirth represented by the first and second quintiles (low-income earners) decreased over the past decade, the percentage of childbirth represented by the fourth and fifth quintiles (high-income earners) increased. This suggests that childbirth is becoming polarized in line with income and wealth levels.

Jung Jong-cheol, is an office worker in his 40s with a household income of 15 million won (US$13,000) a month. A few years ago, he and his wife gave birth to their third child at home. “We chose home birth because we could have a child in the ideal environment rather than in a hospital where there are artificial and invasive procedures like pain control,” Jung said.

Since home birth is not yet covered by health insurance, it costs at least 1 or 2 million won. Jung and his wife currently spend about 8 million won a month on their three children, including the cost of tutoring and private education. Home births, which have recently become more popular among high-income earners, and postnatal clinics in Seoul’s Gangnam neighborhood that can cost 20 million won for a two-week stay offer a stark contrast with low-income earners who are forced to delay childbirth because of the financial burden.

One of the main reasons that people are hesitating to have children is the rising cost of housing. Many people are putting off children until they can find a stable place to live.

“When I got married, we rented an apartment by putting down 83 million won (US$72,150) of key money, but now we’re paying 250,000 won (US$217) a month in rent on top of a 70 million won (US$60,880) deposit,” said Han Hye-jeong, 41, an office worker who has been married for 12 years. Han says that as a child she never dreamed that she might never become a mother, but several years ago she set aside her plans to have children.

Han Chang-geun, a professor of social welfare at Sungkyunkwan University, recently used data from the South Korean labor panel to assess 1,062 couples who married for the first time and formed households after 2000. In his study, Han found that couples who bought their house or whose house was worth more tended to have children sooner.

“Something really needs to be done about the problem of housing for newlyweds, which is the biggest financial hurdle when getting married. The only way to encourage young people to get married and have kids is to ensure that they have stable housing,” Han said.

Marriage not even an option for younger generationIn South Korea, where unmarried people are not socially recognized as adults, the overwhelming majority of children are born to married couples. But a clear trend has emerged in which even marriage is increasingly out of reach. According to Statistics Korea figures, the number of marriages fell from 430,000 in 1996 to 300,000 last year. The total for the first half of 2016 stood at 144,000, a 7.6% drop the year before. Even when people do marry, they are doing so later and later in life: the average age of a woman marrying for the first time was up to 30 last year from 25 in 1990.

Lee Ji-yeon, 28, recently decided to put off marriage for a long time - with a boyfriend she dated on the assumption they would one day wed.

"We actually decided to make a plan for the wedding, and we were at a loss over what we were going to do about a house," Lee said. "Neither of us makes that high a salary, and there are a lot of things we would have to give up if we married now. We decided it would be better to spent a few more years saving up some money to hold the wedding."

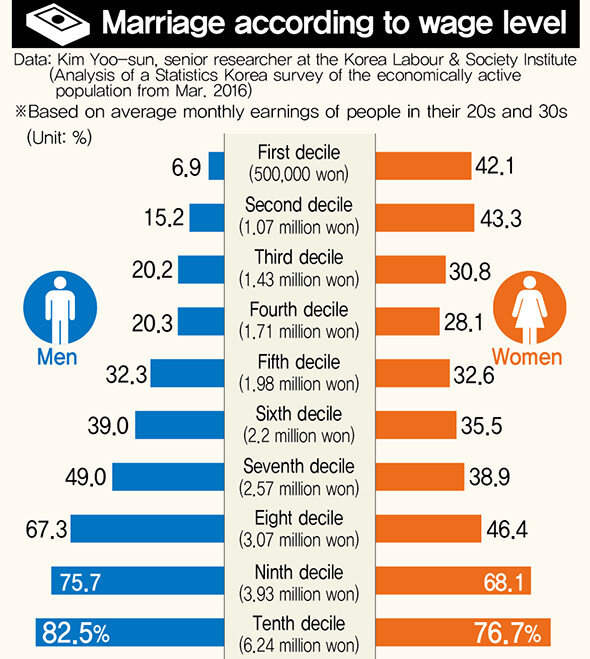

The odds of actually marrying are better the higher the couple's income level. Using findings from a Statistics Korea supplementary survey of the economically active population (wage earners in their twenties and thirties as of Mar. 2016), Korea Labour & Society Institute senior research fellow Kim Yoo-sun analyzed the percentage of married people at different income levels. The results showed a higher rate of marriage at higher income levels when wages were separated into deciles.

"South Korea's marriage market is one where a 'male-as-breadwinner' model dominates, and a stable job and suitable wage for the male was found to have a large impact on age at marriage and childbirth," Kim said.

"The current low birth rate policies, which are focused mainly on supporting women who are already married with childbirth and child-raising, need to be changed to provide stable jobs to young people, if they are going to be effective," he added.

Experts suggested that if the South Korean government wants to respond effectively to the low birthrate, it should focus on eliminating the social and economic factors that prevent people from having children even when they want to.

"We should pay attention to the way even making a family is becoming increasingly stratified in South Korean society," said Seoul National University sociology professor Park Keong-suk.

"This means people are limited in their ability to get married, have children, and start a family," Park added. "We also need to relieve income and gender inequality to prepare for changes in the demographic structure."

Working at the behest of the Ministry of Strategy and Finance, Korean Women's Development Institute researcher Kim Young-ran published a report last year on a study of ways to boost the effectiveness of low birth rate policies.

"Even if we identify the younger generation's decision to not marry and to put off having their first child as the causes for the low birthrate, the budget focus to date has been on the area of childbirth and child-raising policy," Kim said.

"To encourage young people to start families and have children, we need to increase their chances of a stable entry into the labor market by reducing irregular positions and improving the wage gap," she suggested.

Names of sources in this article have been changed to protect their privacyBy Hwangbo Yon and Park Soo-jin, staff reporters

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 2Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 3[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 6New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 7[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 8Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 9[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 10Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors