hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Analysis] How much will new UN sanctions affect North Korea’s coal exports to China?

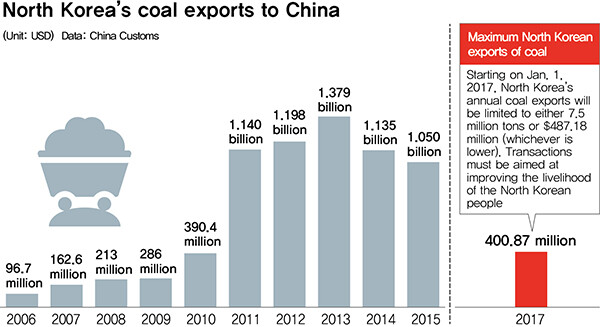

The key sanction against North Korea imposed by Resolution No. 2321, which the UN Security Council adopted on Nov. 30 in response to North Korea’s fifth nuclear test on Sep. 9, is a quota system on North Korea’s exports of coal. The resolution states that the volume and value of North Korea’s yearly coal exports (which must be transactions aimed at improving the livelihood of the North Korean people) will be limited to either 7.5 million tons or just over US$400 million (whichever is lower), starting on Jan. 1, 2017.

Virtually all of North Korea’s coal exports go to China. The main importers are Liaoning and Jilin provinces across the Yalu and Tumen rivers and Shandong, Jiangsu and Hebei provinces across the West (Yellow) Sea. According to figures from China’s General Administration of Customs, North Korea exported 19.6 million tons of coal to China last year, earning US$1.05 billion. Thus, the new sanctions are aimed at reducing the volume and value of the North’s coal exports to about 38% or 39% of last year‘s figures.

The new sanctions are much tougher than Resolution No. 2270, which the UN Security Council adopted in response to North Korea’s fourth nuclear test on Jan. 6. Though the previous sanctions were “the toughest and most effective non-military measures the UN has ever taken” (in the words of South Korea‘s Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Paragraph 29 made an exception for North Korean coal exports that were “solely intended for the people’s livelihood” without any restrictions on volume or value.

The quota system for coal exports was a key point of contention in the sharp debate between the US and China, which were the main parties in the UN Security Council deliberations on the sanctions resolution against North Korea. It is also the primary reason that it took the Security Council 83 days to adopt the resolution, longer than any previous resolution about the North. South Korea, the US and Japan had argued that the “livelihood exception” in Resolution No. 2270 was a loophole in the sanctions and focused their efforts on closing this and other loopholes during the negotiations about the new resolution. The main target was North Korea‘s coal exports.

These efforts were not without their rationale. North Korea’s foreign trade is almost entirely with China, and the export product that earns North Korea the most money in its trade with China is coal. The Bank of Korea estimates that North Korea‘s foreign trade last year (excluding inter-Korean commerce) was worth US$6.25 billion, of which US$5.71 billion, or 91.4%, was trade with China. On top of that, North Korea earned US$1.05 billion from coal exports last year, amounting to 39% of North Korea’s total of US$2.7 billion in exports to China. This means that there if there is one single product that could be restricted to effectively reduce the money that North Korea earns through legal trade, that product is probably coal. “By simply implementing a quota system for coal exports, we can expect North Korea’s cash receipts to be reduced by about US$600 or 700 million dollars a year,” said an official from South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

But there is overwhelming skepticism about whether the quota system for coal exports is strategically disruptive enough to break North Korea‘s commitment to developing nuclear weapons and missiles. Considering the technical difficulties of verifying when the quota has been exceeded and restricting such excesses along with the extensive smuggling between North Korea and China, it is widely expected that “North Korea and China will soon find a loophole,” in the words of one South Korean government official.

But most importantly, it is the general view of experts that it is inconceivable that this much “extra pain” would force North Korea to give up the “two-track program” of building the economy and nuclear weapons, which was defined in the resolution adopted by the 7th Congress of the Korean Workers’ Party in May as its “permanent strategic course.” That is why many believe that stronger sanctions are likely to spark further conflict resulting from the stalemate on the Korean Peninsula or a backlash from North Korea, unless an effort is made to find a way out through dialogue and negotiations based on the Six-Party Talks and the Sep. 19 Joint Statement, which were mentioned both in Resolution No. 2270 and in the new resolution.

By Lee Je-hun, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 2Yoon’s broken-compass diplomacy is steering Korea into serving US, Japanese interests

- 360% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 4[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 5After 2 years in office, Yoon’s promises of fairness, common sense ring hollow

- 6S. Korean first lady likely to face questioning by prosecutors over Dior handbag scandal

- 7AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 8[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 9[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

- 10‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be