hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

History of corruption: different generations of chaebol implicated in scandals

Back then, it was the father coughing up the money. This time, it was the son. Back then, it was the father’s administration demanding payment. This time, it was the daughter taking it as President.

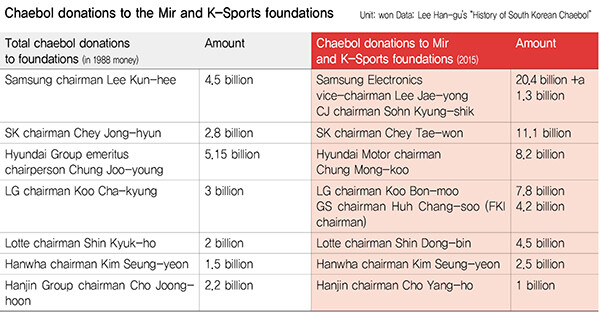

Nine chaebol chairmen that made “contributions” to the Mir and K-Sports Foundations are appearing on Dec. 6 before a special parliamentary audit committee to investigate allegations of government interference by Choi Sun-sil and other non-elected figures. A second-generation example of government-business collusion resulted in the largest number of top-ranked chaebol chairmen ending up at a hearing. A growing number of people are now calling for a close look at the roots of this deep-seated collusion - and basic measures to put an end to it.

Before South Korea became a democracy in 1987, government-business collusion was rooted in the primacy of political power. According to research findings - including those found in University of Suwon professor Lee Han-gu’s “History of South Korean Chaebol” - collusion between the government and chaebol date back to South Korea’s establishment in 1948.

“Business was directly linked to the government,” writes Lee of the collusion practices that took place under the Rhee Syng-man administration (1948-1960). The government had immense power over economic activities. It was the government that disposed of and distributed to corporations the assets that had been left by imperial Japan and the huge amounts of aid goods provided by the US. Financial institutions were state-owned for a time after the government was formed, but in 1957 bank shares were sold off, giving the chaebol control over the financial industry too. In the post-Korean War era, government-ordered efforts accounted for a large share of construction demand. Rhee’s Liberal Party administration chiefly received its political funds from construction companies that had won government bids.

The collusion only deepened in the 1960s and ’70s as the Park Chung-hee regime pushed a program of government-led economic growth. When it came to power in a coup on May 16, 1961, the regime made its “revolutionary pledge” to “eradicate corruption and misdeeds.” It was not kept. While Park did apply some pressure shortly after the coup by arresting businessmen suspected of collusion, he soon changed his tack. This was also the period when the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI) came into being.

“Shortly after taking office, the revolutionary government [the Park administration] began routinely engaging in corruption in various areas that was worse than what the established politicians had been doing,” wrote former CJ Group emeritus chairperson Lee Maeng-hee in his memoirs.

“The most serious involved the government secretly sticking its hand out for various business permits and approvals,” Lee added.

The collusion continued worsening in the ’80s. Then-President Chun Doo-hwan (1980-88) had assisted Park from up close three times before, including as secretary for the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction. Chun’s methods were similar. He received political funds directly from companies while in office; as he prepared to step down, he created the Ilhae Foundation and funded it with forced contributions. Six of the chaebol that paid out to the Mir and K-Sports Foundations had also funded the Ilhae Foundation 28 years before. A number of the chaebol chairmen who gave to Ilhae were fathers of the ones who “contributed” to Mir and K-Sports.

In 1988, former Hyundai Group emeritus chairperson Chung Joo-young triggered controversy by declaring at the Ilhae Foundation hearings that there had been coercion. But the Supreme Prosecutor‘s Office central investigations division opted to indict only former Chief of Staff Jang Se-dong in Jan. 1989 - without investigating either Chun or his successor, then-President Roh Tae-woo (1988-93). Kim Ki-choon, former Chief of Staff to President Park Geun-hye, was in command of the investigation at the time as Prosecutor General. As fate would have it, the same man who directed a tepid investigation back then was named this time as a witness for the latest hearing.

Government-business collusion diminished in scope after democratization in 1987, but never went away completely. Party management became relatively transparent; it was presidential election funds that proved problematic. Chun and Roh ended up belatedly punished for receiving hundreds of billions of won from companies to use as presidential funds in Dec. 1987. Also erupting belatedly during this time was the “Samsung X-file” case, in which it emerged that Samsung and other major corporations had provided illegal political funds to the ruling and opposition parties in the 1997 election. A 2002 investigation into presidential funds uncovered over 80 billion won (US$68.6 million) received by the Hannara Party (predecessor of the current Saenuri Party) and over 10 billion won (US$8.6 million) received by the New Millennium Democratic Party (the former incarnation of the current Minjoo Party). The famous “carload of money” incident - in which the Hannara Party received a huge amount of cash - dates to this time.

By the ’00s, the increased power enjoyed by corporations made collusion more of an exchange-based affair. Corporations less frequently made open political donations as they had done in the past. The change was also the result of the real-name system for financial transactions, which went into effect in 1993. Instead, secret transactions are widely suspected of having been conducted through legal means to win business permits and approvals.

“The key difference with government-business collusion in the ‘00s was that the chaebol were now more powerful than the government,” writes Lee Han-gu.

“Where the relationship before had been vertical, this was now a situation where the chaebol were more powerful, where they no longer dropped to their knees and crawled at demands to pay up, but made contributions as exchanges at the transactional level,” he continues.

It is this kind of practice that the chaebol chairmen selected as National Assembly witnesses are suspected of engaging in. Many believe Samsung, Lotte, and other chaebol complied with the administration’s improper demands because of their own interests - National Pension voting rights, duty-free shops, and pardons for chaebol chairmen among them.

Some now say rooting out this kind of collusion will first require adjustments to the constitution of the empowered corporations.

“The chaebol families that did not shy away from illegal and illicit acts brought this kind of extortion and intimidation by behind-the-scenes power brokers on themselves. The chaebol are accomplices to government-business collusion, not victims of it,” wrote Hansung University professor Kim Sang-jo in a recent opinion piece.

“We need to make corporations that don’t have enough for [the administration] to extort anything from. The way to do that is through governance structure improvements, chaebol reform, and economic democratization,” Kim argued.

Others are saying the public needs to more closely monitor the government, including its investigative agencies.

“We need to create a situation where the government and companies don’t give and don‘t receive in return,” said Lee Han-gu.

“Administration needs to be made more transparent, democratization needs to be promoted more, and there needs to be more public monitoring of the institutions of power,” he advised.

By Ko Na-mu, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 2Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 3[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 6[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 7Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 8New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 9[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 10[Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?