hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] A county where, without foreigners, the factories would close

As soon as the job placement agency in Eumseong County, North Chungcheong Province, opened for the day, at 7 am on Nov. 28, dozens of foreigners lined up at the counter. Agency staff started yelling for the applicants to give them their phone number and passport. Being added to the waiting list was simpler than I thought. Foreigners that the staff recognized only had to give their names without even showing their passports.

“I just hope I don’t get a job at a kimchi factory,” said a 23-year-old woman (“K”) from Malaysia, alluding to the hard working conditions at such factories. K arrived in South Korea on a three-month tourist visa, but she has already been working in the country for more than a year as a day laborer, making 54,000 won (US$45.50) a day.

That morning, 180 people visited the job placement office over the course of about two hours, and 140 of them got jobs. Agency staff transported the workers to more than 20 sites on small buses and trucks. In Eumseong, there are no fewer than 64 such job placement offices that are operating under county permits. Most of them provide jobs for foreigners.

It‘s illegal to provide work to foreigners who don’t have a work visa. While the country’s immigration office periodically cracks down on the practice, the number of foreigners coming here does not decline. “If the job placement agencies in Eumseong were to close their doors for a single week, the factories here would all go out of business,” said the agency director (“N”).

After 9:30 am, N said he sometimes turns off his mobile phone. Those are the days when he fails to meet the number of workers requested by factories the night before. If he doesn’t turn off the phone, it will ring off the hook with complaints from factory managers who want more workers or who are trying to get a production line running.

Eumseong has already become a “little Asia”: there’s a mosque that Indonesian workers chipped in to build, and Cambodian workers take home microwaves as prizes from countywide singing contests. According to a census by the government statistics office, 10,288 of the 102,023 people living in the county last year, or 10.1%, are foreigners. That’s the third-highest foreign population rate among major administrative districts in South Korea, after Seoul’s Yeongdeungpo District (12.1%) and South Jeolla Province’s Yeongam County (10.2%).

Population size is typically determined by domestic births and deaths, but today migration is becoming another significant variable. According to future population estimates for 2010-2060 (median households) by Statistics Korea, South Korea’s population decline was expected to begin in 2028. Thanks to the migrant influx, the actual decline date is expected to come later, in 2031. Some are now saying that with a rebound in the birth rate unlikely to come any time soon, increasing migrant numbers should be seriously considered as a way of addressing the future population decline and labor shortage. While the government previously kept its role confined to policies for using overseas workers over the short-term to meet demand for so-called “3D jobs” (dirty, dangerous, and demeaning), the argument suggests it is now time to devise a new migration policy to gird for the coming population shock.

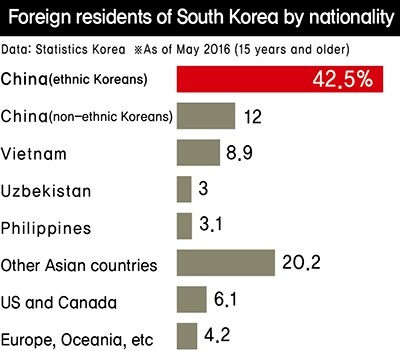

One out of ten Eumseong residents foreign

As of June 2016, the number of international residents in South Korea had passed two million. The UN categorizes “immigration” as stays of longer than three months (90 days) in a foreign country. Those staying three months or more are classified as short-term migrants; long-term migrants are those remaining for a year or longer. By this standard, the number of immigrants in South Korea - i.e., those staying longer than three months - stood at 1.48 million according to June statistics from the Justice Ministry on international residents. While they represent a very small 2.9% of the total population, the increase in numbers has been steep. As recently as 2000, South Korea had just 220,000 long-term international residents; sixteen years later, the number is around seven times higher.

The phenomenon has resulted from a mixture of the 2004 institution of the employment permit system, measures in 2007 to allow visiting employment by ethnic Koreans from China, and increases in marriage migration and exchange students. Indeed, the arrival of large numbers of Korean-Chinese immigrants raised the number of Chinese nationals on long-term sojourns from 59,000 in 2000 to some 800,000 as of June this year. The number of foreign exchange students rose from 4,000 to 100,000 over the same period. Marriage migrant numbers climbed from 25,000 in 2011 to 150,000 as of June 2016. Of those, 110,000 have obtained South Korean citizenship.

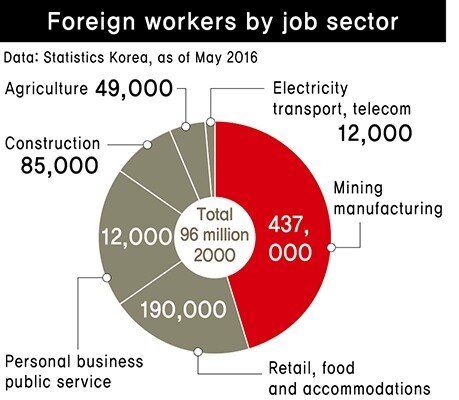

The big driving force in the rise in long-term international residents has been employment. According to studies of international resident employment conducted every year by Statistics Korea, a total of 962,000 international residents were employed in South Korea as of May this year. Most worked in manufacturing (430,000) or wholesale/retail sales and hospitality/restaurants (190,000). 69%, or 662,000 people, were employed at small enterprises with fewer than 30 employees.

Foreign workers account for 3.6% of all employed persons in South Korea. Some regions are heavily dependent on them - which means international residents are driving population increases there. Eumseong is a case in point. In 1996, international residents accounted for just 0.7% of its population; today, one in five residents is from overseas. In the last 20 years, the total population of Eumseong has risen by around 20,000, an increase mostly due to foreign residents. Concerted efforts by North Chungcheong Province to attract factories to its area have resulted in the number of production plants within Eumseong climbing from 1,598 in 2007 to 2,156 as of October this year. Many positions are in meat processing and other 3D jobs that South Koreans shun. It’s a case where international residents are filling the workforce demands.

Saud Lal Bahadur, 39, arrived in Eumseong from Nepal seven years ago.

“When I first arrived, there were only three Nepalis here. Now the number has gotten so high that you‘re going to see one or two every time you board a neighborhood bus,” he said.

Bahadur, who works at a plant producing wall materials, arrived in South Korea through a non-professional work visa on the employment permit system. Other international residents in Eumseong also came through the system, but a number of others visit job agencies to find day labor work like K. International workers on employment visa account for around 5,000 of the 23,000 workers employed at Eumseong’s industrial complex; the county office estimates another 5,000 or so working through unofficial channels. It‘s a case of two sets of interests coinciding: the employers’ desire to cut down on the costs of direct employment and hire workers only when quantities demand them, and the international workers‘ desire to find jobs easily after entering on tourism visas. Job agencies specialize as suppliers, placing international workers in manufacturing, construction, and farm positions.

“The [29] domestic workers at this plant are all in their late forties or older, and the others [16] are foreigners,” said the president of an Eumseong construction materials plant. “It’s tough to find domestic workers who are younger.”

“The reliance on foreign workers at construction sites is high enough that about eight out of ten are Korean-Chinese,” the plant president added.

Replacing low-skilled workers with professionals now an issue

Since 2008, the South Korean government has issued a framework plan on international resident policy every five years. The term “international resident policy” is used instead of “migration policy” because of possible confusion with migrants moving overseas. Instead, past migration policies were aimed at encouraging native South Koreans to move overseas to combat population growth. The first record of this was the emigration of 92 Brazilian farm workers in December 1962 following the proclamation of the Emigration Act earlier that year.

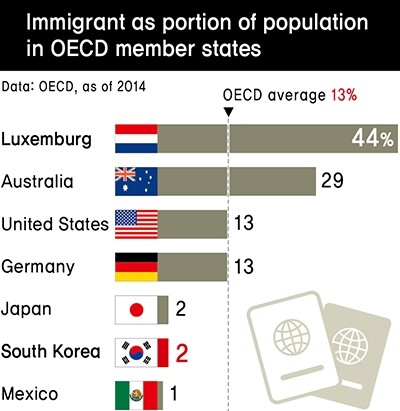

By the ‘00s, various government policies were making reference to foreigners in terms of securing future “growth engines” - but according to experts, there was basically nothing in the way of immigration policies aimed at bringing workers into South Korea. The introduction of the industrial technology trainee system in 1993 marked the beginning of a focus squarely on making short-term use of low-skilled foreign workers. Today, South Korea doesn’t have the kind of systematic statistics on migrants that the major OECD member countries do. Major immigration destinations like the US, Canada, and Australia distinguish between the first-generation “foreign-born population” and the second-generation “migrant background population” who are their children. South Korea only issues statistics on the “foreign population,” meaning anyone with foreign citizenship on a long-term sojourn.

As the low birth rate and aging trends have intensified, the last few years have seen a noticeable change in interest in immigration policy in and around the South Korean government. State think tanks like the Korea Development Institute (KDI) contributed last year to a list of “policy tasks for South Korea’s continued development in the age of aging and low growth.”

“Because it is currently difficult to guarantee success with birth rate promotion policies, immigration policy should be set as a key state strategy and related laws and institutions should be adjusted to broaden the societal debate,” it concluded.

Chonbuk National University sociology professor Seol Dong-hoon explained, “We’ve been living thus far in the ‘population bonus’ era, but the decline in the youth population is going to become more evident and lead to a workforce shortage going ahead.”

“Once we reach the critical point of the population’s aging, we’re going to suffer a shortage not just of low-skilled workers like now, but university graduates too,” he predicted.

Seol’s argument is that the baby boomers’ retirement from the labor market and the arrival of the low birth rate generation born since the ‘00s could lead to a workforce shortage not just in 3D jobs but many others besides. The South Korean government has announced plans to set scales and priorities for immigration when it announces its third framework plan for international resident policy (2018-22) next year. The UN predicts that the continued rise in movement between countries in search of jobs will result in migrants cumulatively totaling 500 million by 2050.

So what sort of immigrant numbers would South Korean need in the future? In 2000, the UN calculated how many immigrants eight countries with low birth rate trends would have to admit within the next 50 years to offset their population aging effects. The calculations were based on forecasts using 1995 populations. The results showed that South Korea would have to admit an average of 129,000 immigrants per year between 2000 and 2050, or 6,246,000 immigrants total (in person-years) over the 50-year-period, to keep its productive population fixed at its highest level. France was estimated to need an average of 109,000 per year over the same period. For the US, the average was 359,000; for Japan 647,000. A more recent analysis by senior research fellow Jung Ki-sun of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) immigration policy research center provides estimates based on future population predictions issued by Statistics Korea in 2011, reflecting a further decline in the birth date from 1995. Jung’s conclusion was that South Korea would have to admit an average of 7,362,000 people per year between 2017 and 2060 to stave off a productive population decline - a massive scale amounting to 19.9% the productive population in 2016.

But experts stress that the immigration issue can‘t be resolved as a simple arithmetic problem of filling the gap left by the population decline with immigrants.

“There are quite a few variables that need to be considered in the debate on how many immigrants we need, including domestic business conditions, the labor market, and reunification,” explained Jung.

“We’re going to need policies to thoroughly analyze immigration demand and to attract outstanding talents and help them settle, rather than focusing solely on short-term labor usage, and there’s going to have to be a debate there on a suitable scale of immigration,” he added.

A particularly serious concern is that if foreign workers continue to be used to alleviate the labor shortage at micro-businesses, the result could be to further reduce the quality of low-paid domestic jobs and delay industry restructuring. A May 2016 study by Statistics Korea showed professionals accounting for just 4.8% of international residents employed in South Korea. The majority work in low-skilled, low-paid jobs. 53% of foreign wage earners make less than 2 million won (US$1,690) a month. An analysis by KDI senior research fellow Choi Kyung-soo estimated that the influx of foreign workers between 2000 and 2008 increased the pay gap between high school graduates and non-graduates by 10% to 20%.

“Maximizing the effect of bringing in immigrants is going to require carefully crafted policies that combine ’substitution cycle‘ immigration where low-skilled workers are sent back home after staying for a fixed period of time, and ’settlement‘ immigration by professionals who can remain on a permanent basis,” said Seol Dong-hoon.

“Immigration has a far-reaching impact on our society, from its wage-lowering and unemployment effects for South Koreans to issues with crime, social service spending, and public finances,” he added. “We need to be able to minimize the side effects and achieve social integration.”

In the US and countries in Europe, side effects like growing income gaps and social conflict from rising numbers of low-skilled immigrants have resulted in various controversies.

“If you look at the country as a whole, the US has benefited [economically] from bringing in immigrants, but the public hasn’t perceived that in their everyday lives,” said Jung Ki-sun.

“Unless structural issues in South Korea like deepening polarization are resolved first, the side effects of bringing in immigrants could grow,” he predicted.

By Park Su-ji, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 4[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 5[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 6Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 9[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 10US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters