hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Will South Korea adopt Bhutan’s gross national happiness policy?

Will President Moon Jae-in implement Bhutan’s “happiness policy” in South Korea? That‘s the hopeful question that people aware of Moon’s unusual connection with the country are asking South Korea’s new government.

In July 2016, before Moon’s presidential campaign had begun, Moon went on a trip to Nepal and Bhutan to clear his mind. While spending two weeks in Bhutan, he met Bhutan’s Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay and its Gross National Happiness Commission Chair Karma Ura. Their explanation of Bhusan’s happiness policy reportedly had a major impact on Moon. “If a government cannot make the people happy, that government doesn’t deserve to exist,” Moon wrote on his Facebook page upon returning to South Korea. The phrase appears in Bhutan’s code of laws.

But the connection didn’t end there. In Oct. 2016, Bhutan’s Minister of Health Tandin Wangchuk returned the favor by meeting Moon during a visit to South Korea. “President Moon said during that meeting that he would implement Bhutan’s happiness policy if the Minjoo Party came to power,” said William Rim-jae Lee, president of the Korea-Bhutan Friendship Association, who was present during the Moon and Wangchuk’s meeting, held at the Lotte Hotel Busan.

While South Korea and Bhutan have diplomatic relations, they don’t have embassies in their respective countries. Instead, there is the Korea-Bhutan Friendship Association, which serves as a liaison. The association has more than 1,200 members, including businesspeople and artists - and in Oct. 2016, Moon became the first politician to join the association.

This special connection remains intact today. The first foreign leader to speak with Moon on the phone after the confirmation of his election as president around midnight on May 9 was Bhutan’s Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay. While this was an unofficial conversation, it was unusual for Moon to receive his first congratulations from the leader of a small country instead of one of the major powers, as is traditionally done.

It seems clear why Moon is interested in Bhutan - it’s regarded as the happiest country in the world. Located between China and India, this tiny Buddhist country has a population of over 750,000 living in an area half the size of South Korea. But Bhutan also shocked the world when Britain’s New Economics Foundation announced in 2010 that 97% of its people were happy, giving it the highest ranking on the world’s happiness index.

These results are backed by Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Commission, which was set up in 2008 and reports directly to the king. From 1972, when Bhutan was incredibly poor, until today, when growth has brought it to the ranks of the developing countries, its guideline for governance has not been GDP (gross domestic product) but GNH (gross national happiness). Bhutan‘s governing philosophy is that a country’s development should be defined by how happy the people are.

In line with this, Bhutan has established and executed regular five-year plans to improve gross national happiness. There are four pillars for the country’s happiness policy: achieving economic growth that is high but fair; conserving the ecosystem on the understanding that neighbors, animals and nature should be happy, too; updating traditional values and institutions so that they can be maintained in a progressive society; and establishing an efficient and transparent government that welcomes the people’s participation and takes responsibility for their needs.

On this foundation, 33 indicators have been designated in nine domains to measure the national happiness index, which is then reflected in policy. These nine domains are living standards, psychological wellbeing, health, time use, education, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, and ecological diversity and resilience. The idea is that happiness depends upon all these elements being in place. When subsequent national happiness surveys find people in a condition of unhappiness, the government implements policies that are tailored to them.

After the kingdom of Bhutan was united in 1907, it was initially an absolute monarchy, but the fourth king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, converted the government into a democratic constitutional monarchy from the belief that “since it’s very dangerous for a single person to decide the destiny of a country, the people ought to make those decisions through their own power.”

It was also King Wangchuck, the country’s fifth, who introduced the national happiness index, which has spread around the world since then. The US partially adopted the concept of the national happiness index in 2006, the government of Thailand set up a national happiness index center last year, and the United Arab Emirates has adopted the policy as well, with the Dubai government appointing a “Minister of Happiness.”

Park Jin-do, 65, professor emeritus at Chungnam National University, published a book called “The Secret of Bhutan’s Happiness” after studying Bhutan’s happiness policy during a two-month trip there in 2015. “As South Korea enters the era of low growth, social divisions are already too severe to be resolved through growth policies alone. The time has come for South Korea to adopt national happiness as a basic principle for state policy, too. We need to establish a ‘gross national happiness commission’ to create strategy for national happiness and coordinate various committees related to jobs, state education and rural areas, and we need to use that commission as a compass for governance,” Park suggested.

While it’s clear that Moon has taken a great interest in Bhutan’s happiness policy since before he began his presidential campaign, he has yet to explain how the new administration means to put this into practice. A source at the Blue House said they “haven’t heard anything yet” about setting up a happiness commission. “Transcending efficiency and individuals’ interests and prioritizing social values, or in other words ‘happiness,’ while making policy decisions is also significant in economic terms,” said a key member of Moon‘s election campaign. Could happiness, rather than growth, become established as a basic policy principle in South Korea as well?

By Cho Yeon-hyun, religion correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

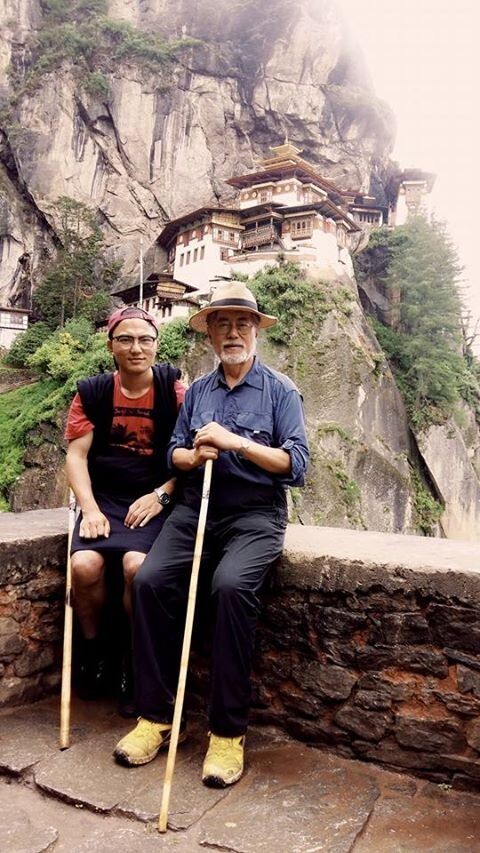

President Moon Jae-in meets Bhutan’s Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay, in Bhutan, July 2016. (from Moon Jae-in’s Facebook page)

President Moon Jae-in meets Bhutan’s Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay, in Bhutan, July 2016. (from Moon Jae-in’s Facebook page)

President Moon Jae-in (center) meets with Bhutan’s Minister of Health Tandin Wangchuk (left) and William Rim-jae Lee, president of the Korea-Bhutan Friendship Association, in Busan, Oct. 2016.

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong? [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/8517133419684774.jpg) [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?![[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/6817133413968321.jpg) [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 3S. Korea, Japan reaffirm commitment to strengthening trilateral ties with US

- 4Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 5[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 6Gangnam murderer says he killed “because women have always ignored me”

- 7Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 8[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 9Korea, Japan jointly vow response to FX volatility as currencies tumble

- 10[Column] “Hoesik” as ritual of hierarchical obedience