hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Debate over working hours asks, what makes a week, five or seven days?

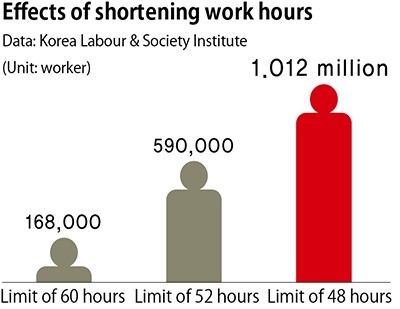

The Moon Jae-in administration is planning to amend the Labor Standards Act or abolish the Ministry of Employment and Labor’s administrative guidelines to lower the legal maximum working hours per week from 68 to 52. The issue is already the subject of debate in the Supreme Court. Fourteen cases are currently pending; in 11 of them, a lower court ruled that the maximum number of working hours per week was 52. In only three of the cases did the courts rule for 68 hours as per the ministry’s guidelines. But despite the referral of some cases for en banc rulings(which are decided by a panel of judges), the Supreme Court has been quiet, with no final rulings produced in the last five years and five months.

On Dec. 18, 2013, the Supreme Court issued an en banc ruling that regular bonuses counted as “regular wages.” The verdict came in a suit filed by current and former workers against the automobile parts company KB AutoTech to demand severance pay. The case ended up having a serious ripple effect. Regular wages represent the basic amount by which companies calculate the various rates when workers work overtime or on nights and holidays. Including regular bonuses in those wages would greatly increase the compensation received by workers. Companies could no longer simply force their employees to work extra on the cheap. It was the first step toward improving South Korea’s longstanding problem of long working hours.

The Supreme Court ruling on regular wages also included another gambit at breaking the chain of long working hours. In addition to the question of whether regular bonuses counted as regular wages, KB AutoTech also asked for a court ruling on whether holiday hours were counted toward overtime. The answer came in an Aug. 2015 reversal and remand decision: “‘One week’ means seven days, including holidays, and employees who perform holiday work that extends beyond 40 hours a week must receive both holiday and overtime pay.” The verdict overturned a Ministry of Employment and Labor administrative interpretation that had held since the 1953 enactment of the Labor Standards Act, which maintained that “one week” did not include holidays.

Does one week equal five days or seven?

The current Labor Standards Act restricts working hours to 40 per week. It states that daily working hours cannot extend beyond eight (not including break times). This is the five-day workweek system, which was instituted in 2004. Employers who do not observe the 40-hour limit per week and eight-hour limit per day may be subject to up to two years in prison or up to 10 million won (US$8,900) in fines. At the same time, they can extend working hours by up to 12 per week by labor-management agreement. As a result, the legal maximum of allowable working hours stands at 52.

Reality is a different story. OECD data put the number of yearly working hours for South Koreans in 2015 at 2,113. The total was 347 more than the 1,766-hour average for the organization’s member states over the same period. South Korea ranked second, 113 hours behind first-place Mexico (2,246 hours).

MOEL’s interpretation bears much of the blame for the long working hours in South Korea. The ministry has consistently interpreted “one week” in the Labor Standards Act as meaning “days on which an employee is obligated to work,” arguing that holiday hours are not included as overtime. By this interpretation, a five-day week and 40-hour system mean that employees can perform up to 12 hours of overtime and 16 hours of holiday work - eight hours each on Saturdays and Sundays. The result is that even after a 40-hour work week was instituted, the maximum allowable working hours in one week is 68. Back when the work week was 44 hours - including Saturday mornings - the maximum number of working hours per week was 64 (the 44 legally

designated hours plus 12 hours of overtime and eight hours on Sundays). Yet after Saturday became a day off, the maximum number of hours per week actually increased to 68 (40 legally designated hours plus 12 hours of overtime and 16 hours on Saturdays and Sundays). While meant to reduce long hours, the four-hour reduction in legally designated working hours actually resulted in a four-hour increase in the total hours because of the ministry’s administrative interpretation.

11 out of 14 courts through second trial ruling call for double pay

By law, workers receive time-and-a-half for night and holiday work. For example, a worker who makes 100,000 won (US$89) a day in regular wages would receive an additional 50% for overtime or holiday work, for a total of 150,000 won (US$134). When an employee works on a holiday past the legally designated 40 working hours, it counts as both holiday work and overtime, resulting in double pay (50% extra for holiday work plus 50% extra for overtime), which should bring pay up to 200,000 won (US$179). In other words, holiday wages end up amounting to double the employee’s weekday pay.

But companies have only been paying 50% over regular wages for holiday hours, citing the government’s administrative interpretation. Since that interpretation holds that holiday hours are not included as overtime, it means that anything under eight hours of holiday work is not considered overtime.

The issue of double pay for holiday work first became the focus of a debate in courts in 2010, when former cleaning workers with the city governments of Seongnam and Anyang in Gyeonggi Province began filing lawsuits. A total of 14 cases are currently pending in the Supreme Court after first and second trial rulings. In an analysis of past rulings, the Hankyoreh found courts through the second trial predominantly agreeing - by an eleven-to-three margin - that the maximum number of weekly working hours is 52. An overwhelming majority concluded that employers had to pay overtime as well for holiday work beyond 40 hours a week.

Most of the court’s rulings acknowledging eligibility for double pay were consistent with the law’s aims and common sense. To begin with, double pay was instituted in the Labor Standards Act to require monetary compensation for overtime, night, and holiday work that limits employees’ free time and causes fatigue and stress, and to discourage the practice by imposing financial penalties on employers. Second, common sense dictates that “working hours” mean actual working hours, including holiday hours, and that “one week” should be understood to mean a calendar week, or seven days in a row. This means the legal standard for working hours is 40 hours per one seven-day week. Third, holiday hours beyond a 40-hour work week need to be discouraged for the sake of workers’ health and a humane living standard, since they may cause greater fatigue and stress for workers than holiday hours as part of a 40-hour work week. Fourth, double pay is significant in preventing employers from increasing holiday work to force long working hours without hiring additional employees.

Ultimately, most of the rulings concluded that the interpretation of “one week” as referring only to the days when employees are obligated to work (Monday to Friday) and not holidays runs counter both to Supreme Court precedent holding “working hours” to mean real working hours, and to the aims of the double pay system according to the Labor Standards Act. In particular, they ruled that the MOEL interpretation rendered the act’s restrictions on weekly working hours meaningless, since employees could demand holiday work if they wanted.

“The [ministry’s] misguided interpretation is merely something that should be changed. There is no reason to maintain a mistaken interpretation,” one court ruled. The message was that the MOEL administrative interpretation putting the maximum allowable working hours at 68 per week should be abolished, and the new maximum should be set at 52 hours.

Minority of rulings call for “new legislation”

Most of the rulings also had a completely different take on the Mar. 1991 Supreme Court ruling that served as the basis for MOEL’s administrative interpretation. In Mar. 1991, the Supreme Court ruled that when calculating pay for holiday work, anything under eight hours should receive time-and-a-half, while anything above eight hours counted as overtime as should be subject to extra pay amounting to 100% of regular wages. MOEL used this as a basis for concluding that holiday work under eight hours a week should simply be paid as time-and-a-half, with no double pay.

But many of the courts argued that the case in question involved a request for double pay for work beyond eight hours at a daily level, which was acknowledged by the court. The courts concluded that the legal principle for double pay still held for holiday work beyond 40 hours a week. This means that just as holiday work beyond eight hours a day counts as both holiday work and overtime, holiday work beyond 40 hours a week should also be recognized as both holiday work and overtime. Many of the courts argued that interpreting anything below eight hours as being subject to holiday pay alone had the effect of too narrowly restricting applicability of the double pay principle - resulting in irrational practices that rendered the principle ineffective. By their reasoning, the overtime restriction for the weekly limit of 40 hours was being disregarded, and only the daily limit (eight hours) was being applied. At the same time, a minority of rulings opposed double pay on the grounds that it might cause confusion, while suggesting that legislation may be necessary.

“If holiday work is interpreted as being included in overtime, this leads inevitably to the conclusion that overtime and holiday work together cannot exceed 12 hours,” one court said. “This is an administrative and criminal sanction that has not been adopted since the Labor Standards Act was enacted in 1953. If holiday work is interpreted contrary to practice as being subject to working hour restrictions, this will result in considerable confusion.”

The argument is that with employers being subject to penalties for violating working hour restrictions or failing to pay overtime and holiday rates, acknowledging only 52 maximum weekly working hours and demanding double pay for overtime on holidays now would leave many current employers subject to punishment - resulting in chaos for workplaces. On this basis, a few of the courts have concluded that including holiday work as subject to working hour restrictions (the 52-hour work week) would require separate legislative action.

Supreme Court silence at five years, five months...and counting

The Supreme Court currently has 14 cases pending on the issue. The first was accepted on Dec. 28, 2011, while the most recent was accepted on Aug. 5, 2016. While some have been referred for en banc rulings, the Supreme Court has remained silent for the last five years and five months.

During that time, a new administration has taken office. The Moon Jae-in administration has said it plans to push for amendment of the Labor Standards Act during next month’s National Assembly session. Barring some progress in discussions, it plans to go ahead with honoring Moon’s election pledge to abolish the MOEL administrative interpretation excluding holiday work from overtime hours and reduce the legal working hours to 52 per calendar week. As the body with ultimately interpretative authority for the law, the Supreme Court has little time left to make its voice heard.

By Jung Eun-joo, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 4‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 5[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 8[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 9Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 10[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father