hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

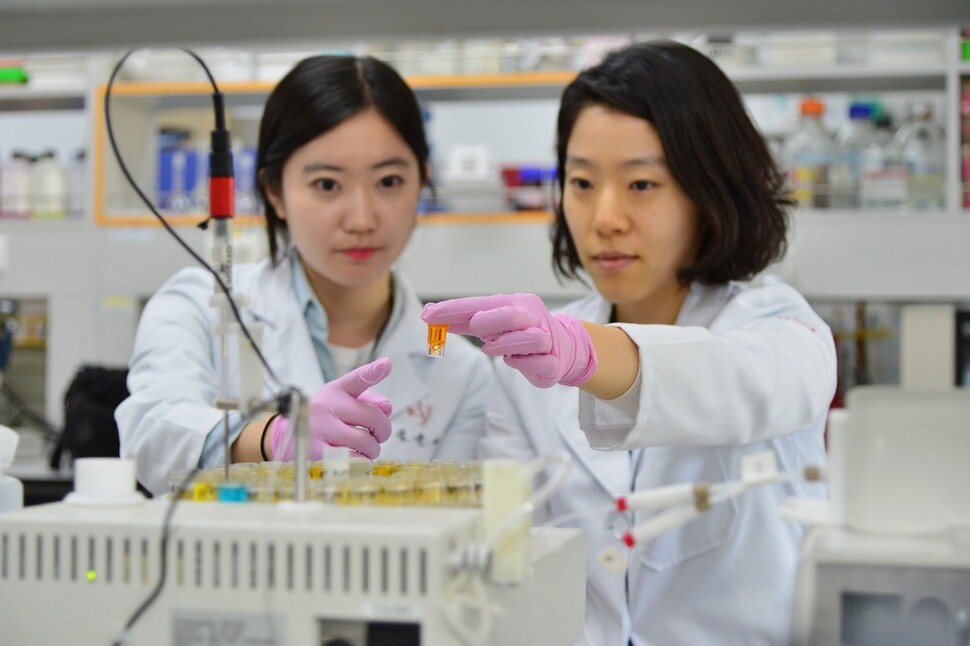

KIST gearing up to conduct doping tests for Pyeongchang Olympics

The Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST), in Seoul’s Seongbuk District, has been designated as an “important state facility” and is thus subject to the strictest security protocol. But inside the KIST facility, there is a building that not even KIST employees can access. The elevator on the six-story L4 research building only goes up to the fifth story. The freight elevator, on the other hand, just stops on the first basement level and the sixth floor, skipping floors one through five. This is the location of South Korea’s Doping Control Center.

The Doping Control Center is a laboratory that handles doping tests for athletes participating in sporting competitions not only in South Korea but in neighboring countries as well. The center undergoes a test each year. The center was established in 1984, in preparation for the Seoul Olympics in 1988, and it has been accredited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) every year since 1999, when WADA was launched. For the center to serve as the official anti-doping lab during the Winter Olympics taking place in Pyeongchang, Gangwon Province, this coming February, it needs to pass WADA certification.

“This year alone, we’re undergoing two due diligences. The due diligence is still underway, so we should be able to renew our certification in mid-January. We’re planning to initiate the doping tests after we start receiving samples on Feb. 1, when the athletes arrive at the Olympic village,” said Kwon Oh-seung, the director of the Doping Control Center.

The job of doping testing is divided between the state-run anti-doping organizations that collect samples from the athletes and the anti-doping labs that carry out the tests. There are anti-doping organizations in more than 200 countries, and the one in South Korea is called the Korea Anti-Doping Agency (KADA). But not every country runs its own anti-doping lab, and those that don’t are obliged to have their samples tested at a lab in a country nearby. Because of the yearly accreditation process, the number of anti-doping labs fluctuates. Recently, Mexico regained its accreditation, while Romania lost its accreditation.

The accreditation process for anti-doping labs is extremely tough. Regular examinations are held three times a year, with five or six samples delivered each time. Getting even one of the testing results wrong is disqualifying. There’s also a “double blind” test in which five samples are slipped into the more than 6,000 samples that the Doping Control Center processes over the course of a year. Since the doping testers have no way of knowing which samples are part of the accreditation—in other words, whether they’re being examined or not at any given time—they basically have to test every sample as if it were part of the accreditation examination.

If one of these “spy samples” is negative but testers flag it as positive, the lab automatically fails accreditation. This part of the examination is so strict because, in a real testing scenario, a false positive could do genuine damage to an athlete. In the case of positive samples, two false negatives lead to disqualification.

A more rigorous accreditation process

Since the state-sponsored doping that occurred during the 2014 Winter Olympics in the Russian city of Sochi, WADA has made its review process more rigorous, causing a large number of anti-doping labs to fail the accreditation examination. In 2015, there were 35 laboratories in 32 countries, but as of this November, that number was down to 28 in 25 countries. And since the Rio Olympics last summer, WADA has tightened security by dispatching investigators, creating a program for whistleblowers, and requiring the installation of security cameras. WADA has not been ranking the anti-doping labs on their scores in the yearly accreditation exams, but starting next year it plans to publicize the exam scores. You might say that anti-doping testing itself is becoming something of an Olympic sport.

“At the moment, the testing methods used by the anti-doping labs are proprietary technology, not standardized technology. WADA is probably introducing the ranking system in an attempt to standardize lab quality by providing assistance and technology transfers to low-ranking labs that are believed to have an inferior capability,” said Son Jung-hyun, a senior researcher at the Doping Control Center.

Doping testing begins on the field. When a competition is over, a doping control volunteer, called a “chaperone,” is assigned to each athlete who earned a medal and to a number of other athletes selected at random. The athletes are guided by their chaperones to the “doping management room” located close to the site of the competition, where urine or blood samples are collected under the supervision of a doping tester.

Urine is collected in most cases, but blood tests are taken from about 15% of athletes, depending upon the event in question. There are no differences between the summer and winter Olympics. Blood samples are taken, for example, in endurance-based events, such as cross country, marathon and swimming, in which improving the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood would lend an advantage. Urine samples are taken for events that rely heavily on the muscles.

The samples are placed in two containers, one 60ml and one 30ml, which are then sealed. While the athlete’s personal information is recorded on the doping management form, only a seven-digit number derived from a random number table is written on the sample container. It’s impossible to tell from the container alone which athlete it belonged to. When the sample containers arrive at the Doping Control Center, the doping testing gets underway. It’s expected that over 4,000 samples will be tested during the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics.

After using special equipment to break the plastic lid on the sample containers, the doping tester stores the 60ml container in a refrigerator at 4 degrees and the 30ml container in a freezer at 20 degrees below zero Celsius. The 30ml container is preserved so that, if an athlete objects to testing positive on the 60ml container, a second test can be conducted in the presence of the athlete or their deputy. The athlete is responsible for paying the cost of a second test.

Testing searches for hundreds of drugs and metabolites

There are over 400 forbidden drugs, but the number of metabolites produced when these drugs enter the body is over 800 at a conservative count, since some drugs produce multiple metabolites. Different equipment is required depending on which drugs and metabolites are being analyzed. The metabolites of some drugs can be detected using a traditional mass spectrometer or the electrophoresis method, while others must be detected through the antigen-antibody method or by using radioactive isotopes as biomarkers.

A mass spectrometer is unable to distinguish male hormones in the body from testosterone mass-produced in plants. In this case, equipment that detects the ratio of carbon isotopes can be used to determine the source of the substance, since plants and mammals have different carbon isotope ratios. That was the method used to detect testosterone in South Korean swimmer Park Tae-hwan.

Recently, technology has been developed for detecting trace amounts of metabolites that remain in the body for a long time, even after the main metabolites vanish after a couple days. Doping designers are also fond of using biologics (a medical substance obtained from biological sources), which are difficult to detect using current analytical techniques because of their similarity to proteins that already exist in the body and because they leave little to metabolize.

“The Doping Control Center is waiting for final approval of technology it has developed for analyzing new biologics. We were one of only five labs that passed the blind tests that WADA carried out on over 30 labs,” said Kwon, director of the center.

By Lee Keun-young, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong? [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/8517133419684774.jpg) [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?![[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/6817133413968321.jpg) [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 3Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 4S. Korea, Japan reaffirm commitment to strengthening trilateral ties with US

- 5[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 6[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- 7Why Israel isn’t hitting Iran with immediate retaliation

- 8Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 9[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 10Strong dollar isn’t all that’s pushing won exchange rate into to 1,400 range