hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Social stigma of being an unwed mother in South Korea remains strong

Early in the morning on Jan. 30 in an apartment in the Duam neighborhood of Gwangju, a 26-year-old woman woke up to a baby bawling. Walking into the living room, she found her 24-year-old younger sister “A” cradling a newborn.

“Whose baby is that?” the older sister asked.

“I brought the baby in because it was crying outside the front door,” A said.

Believing this story, the older sister reported the baby to the police hotline (112) and the emergency hotline (119). But after the police started their investigation, A broke down and confessed.

“The truth is, that baby is mine,” A said. She had given birth to the baby alone in her older sister’s bathroom in the middle of the night.

A, who is unmarried, is currently taking a leave of absence from her junior year of college. The police said that since A did not actually abandon her baby, they would not press charges against her for neglect of an infant. A’s family will reportedly be taking care of the baby.

Why would A have told a lie about bringing in a newborn abandoned in the apartment hallway? It was probably because A felt the same fear and desperation felt by most unwed mothers. The news that a woman has gotten pregnant or had a child out of wedlock imposes severe discrimination and financial hardship. As a result, eliminating the social prejudice about single mothers is critical for reducing infant abandonment.

“When my son went to an orientation before enrolling in elementary school, he was still afraid of getting looks from people because he has the same last name as his mother,” said a woman surnamed Noh, 27, who is raising a seven-year-old boy by herself in Gyeonggi Province. (In South Korea, it’s customary for children to use their father’s last name, while women retain their maiden name even after marriage.)

There are calls for society to embrace single mothers. “I couldn’t tell my family that I was pregnant, but I also wasn’t about to raise the child by myself,” said “B,” a 17-year-old woman who spoke with the Hankyoreh on the afternoon of Jan. 31 at Comfortable House, a welfare facility for single mothers and their children in Gwangju’s Gwangsan District. B, who dropped out of middle school because of family issues, has a six-year-old daughter. While she was living in Gyeonggi Province, she met a 29-year-old man in an online chatroom. When she got pregnant, she was initially at a loss but decided to keep the child.

“I gave birth at a temporary shelter for babies and was planning to give my baby up for adoption, but this video I saw about adopted boys just broke my heart. I didn’t want my daughter to have to feel that way,” B said.

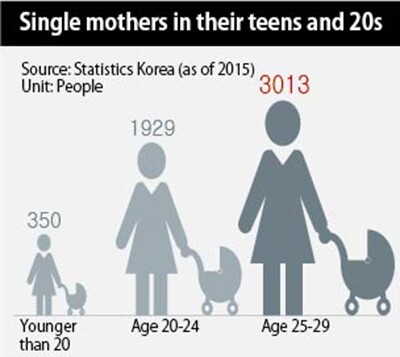

More than 20% of single mothers are in their teens and twenties

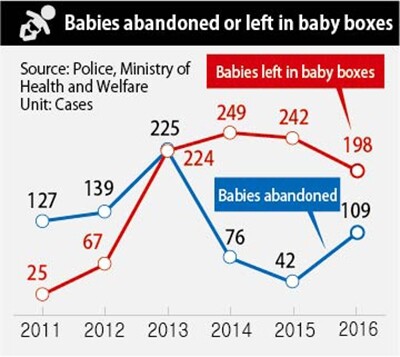

South Korean statistics for 2015 show that there were 5,292 single mothers in their teens and twenties like A and B, representing about 22% of the total number of single mothers (24,000). 92% of the 880 children who were adopted domestically or internationally in 2016 were the children of single mothers. In the same year, 307 newborns were abandoned on the street or dropped in baby boxes. A similar number, 334, were sent overseas for adoption that year.

“Basically, one kid is being abandoned and another is being sent overseas every day,” said one expert.

At first, the central government and local governments only helped single mothers with childbirth, but they have gradually expanded the scope of assistance to raising children and helping the mothers support themselves. There are 62 welfare centers for single mother families around the country. Even so, it’s still hard for these families to stand on their own. Since many of these single mothers have cut off ties with their families, they typically lack the financial means to get a house.

Government support varies by region

Not all local governments help single mother families become independent when they leave welfare facilities: some that do are Seoul (4-5 million won; US$3,700-$4,650), Gwangju (5 million won) and Ulsan (2 million won). Another problem is that single mothers at welfare facilities who manage to get on their feet and start making 1.48 million won (US$1,380) or more a month are no longer eligible for single-parent family assistance.

“This rule incentivizes mothers to keep working part time so that they can stay eligible for single-parent family assistance instead of proactively trying to stand on their own two feet,” said Gi Se-sun, 47, the director of a shelter for single mother families in Gwangju.

“Three months after the agency in question learns that the mother is making the median income, she is removed from the single-parent assistance program,” said an official from the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family.

By Jung Dae-ha, Gwangju correspondent and Park Ki-yong, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Samsung subcontractor worker commits suicide from work stress

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 5Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 6N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 9[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 10[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon