hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special Feature Series #2] Debt troubles mount for South Korean youth

Choi So-won (28, not her real name), who graduated from a private university in Seoul in 2016, took out 19 million won (US$17,700) in student loans from the Korea Student Aid Foundation (KOSAF) while she was in school. “I took out loans for a total of six semesters of tuition, along with one loan [of 1 million won; US$930] for living expenses, so that’s about what it came out to,” Choi said.

For Choi, as a university student, 19 million won felt like shackles from which she would never break free. During her first and second years of university, she managed to juggle work-study and private lessons to pay back 9 million won (US$8,400) of the original loan, but her debt piled up when she took out more student loans the next semester. During her junior and senior years, her focus shifted from part-time work to keeping track of her college credits and preparing for the workforce. “At first, my only thought was that I wanted to pay back my debt as soon as possible. But no matter how hard you try, there’s a limit to how much money you can save as a student, you know? So at some point I just gave up. I figured that there was no way to pay back the money now and that I would pay it back later, after I got a job,” she said.

Readers will not be surprised to learn that no dramatic turnaround was waiting for Choi after she entered the workforce. Since graduating from university in 2016, Choi has been working for a nonprofit organization, and now she realizes just how naïve she was to think she could pay back her loan after getting a job. Choi’s monthly wages – a little over 1.6 million won (US$1,490) before taxes – are barely enough to cover her living expenses. On top of the 10 million won (US$9,300) Choi still owes on her student loans, there’s a bank loan for more than 15 million won (US$13,950) that Choi took out under her own name to pay her sibling’s university tuition last year. “It’s really tough whenever I have an unplanned expense, like my parents’ hospital bill. My monthly salary is barely enough to pay off my credit card bill from the month before. I know I should set up an installment savings account, but the fact is that’s not even an option,” she said.

Choi’s life is similar to the average lives of young people analyzed in a report published by the Seoul Youth Activity Support Center titled “A Study on Developing a Model of Financial Support for Youth in a Transitional Period.” The center’s financial analysis of 136 unmarried young people between the ages of 20 and 34 shows that the first debt most of them ever experience is student loans. They leave school saddled with student loans and then rack up even more debt to cover their living expenses during their job search. And even when these young people do find a job, it has long been routine for them to shift from one poorly-paid, unstable job to another without being able to make a dent in their debt.

Debt begins at school

Noh Su-jeong (29, not her real name), who is between jobs, has recently been working on her application for unemployment benefits. At the end of her two-year contract at her first job after graduating from university, she found herself out of work once again. While she was working on the contract, her monthly wages were around 1.6 million won, after taxes. “I had always been interested in working for an NGO or some other advocacy group, but after living for two years on such a meager salary, I started thinking I might just have to get a job at a regular company,” she said.

While Noh was on her contract job, she gave her parents 800,000 won (US$744) a month, half of her salary. She wanted to help her parents pay back the college loan they had taken out on her behalf. “The thing is I took out a loan for all eight semesters of college. By the time I had graduated, the student loan by itself added up to about 25 million won (US$23,300). I’ve been giving my parents 800,000 won of spending money a month, since I would like to pay back the debt, even if just indirectly.”

Noh said the burden of the student loan was eased a little by the fact that her parents are still gainfully employed and that she was able to live with them. She is still mulling over her career: “I would like to go to grad school and take my studies even further, but my loans and my family’s financial situation make that a difficult choice. When you get right down to it, it’s all because of money,” Noh said.

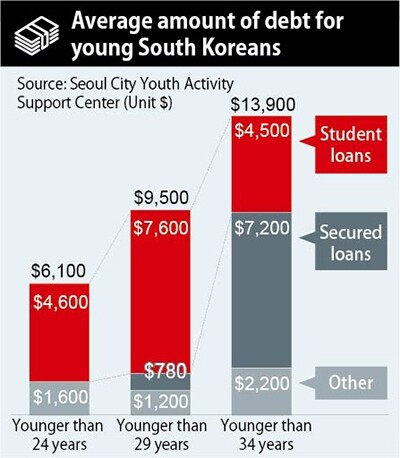

According to the report about youth in transition, 6 out of 10 young people are in debt. They have an average debt of 10.64 million won (US$9,900), of which 6.5 million won (US$5,950) constitutes loans from KOSAF and other public institutions. In other words, most of this debt consists of student loans. The other sources of debt are credit cards (11.8%), unsecured loans (7.4%), and secured loans (6.7%), with overdraft lines of credit and private lenders accounting for 3.7% (490,000 won; US$450) and 2.2% (140,000 won; US$127) of total debt, respectively.

People like Noh who can count on their parents for help are the lucky ones. Those who are left to their own devices in low-wage jobs have trouble just making ends meet, and they are more likely to see their debt increase than to make headway in paying it back. In a survey of young people (between the ages of 15 and 29) that was supplementary to the Economically Active Population Survey released last year by Statistics Korea, the most common salary that young people received in their first job was 1-1.5 million, with 37.5% reporting that range, while the next most common salary was 1.5-2 million, received by 29.6%.

Kim So-yun (27, not her real name), a contract worker for a startup in Seoul, takes home 1.24 million won (US$1,150) a month after taxes. “On top of 5 million won (US$4,650) in student loans, I have 4 million won for living expenses (US$3,720), which means I owe 9 million won (US$8,370) just to KOSAF. I’m not able to pay back the principal. My salary has to exceed a certain amount before principal redemption kicks in, and I’m below that level. I’m just paying the interest, which is 15,000 won a month (US$14),” Kim said. “At least my tuition wasn’t very expensive, since I went to a national university.”

Debt increases with the length of the job search

During that difficult period when people are looking for work, loans are needed even for living expenses. According to figures provided by KOSAF, the portion of loans taken out for living expenses nearly doubled in the seven years from 2010 to 2016, from 317.7 billion won (US$290 million) to 610.7 billion won (US$570 million). These figures confirm the fact that living expenses are amassed as debt during people’s university studies and the job-seeking period when they are transitioning from university to the workforce.

Living expenses are also the biggest worry for Han Se-jin (26, not her real name), who has spent the past year preparing for the job market while making 600,000 won (US$570) a month through piano lessons and part-time jobs. “My living expenses are so tight because there’s only so much money I can make while preparing for my career. The most upsetting thing is when I can’t afford to buy a book I want,” Han said. Han currently has a debt of 13 million won (US$12,100), which includes 10 million won (US$9,300) in student loans and 3 million won (US$2,800) in credit card debt she has accumulated while preparing to apply for work.

“I would use my credit card to cover my living expenses, and whenever I couldn’t pay off my card, I would use the bank’s ‘revolving’ service to convert the remainder to a loan. That’s brought me up to 3 million won in debt. For now, I’ve taken out a government-subsidized ‘sunshine loan,’ which has a low interest rate, to deal with the credit card debt,” Han said.

The job search is also challenging for high school graduates who did not go to college. Lee Ji-yeong (22, not her real name), who works five hours in the morning as a server at a pho restaurant in Seoul’s Cheongdam neighborhood and eight hours in the evening at a fried chicken restaurant in the Heukseok neighborhood, borrowed 500,000 won (US$465) through an unsecured loan this past December. She needed the loan to cover the tuition at the skin care academy she was attending. “It’s stressful to get debt at such a young age, but I couldn’t afford to pay the academy tuition. On top of the tuition, I had to pay about 250,000 won (US$230) a month for model fees and other training expenses,” Lee said.

While Lee did manage to receive her certification as a skin care specialist, she said she has put off entering that field for now. “I had interviews at three skin care clinics and was offered a job at all of them, but I turned them down because they’re too far from my parents’ house. Since I don’t have enough money to move out on my own, I’m planning to save up money doing part-time work and get another beauty-related certification before I start my career,” she said.

For young people looking for a job while in debt, the transition to the workforce is truly a time of hardship. As the job search drags on, living expenses become a bigger burden, but the lack of credit makes it hard to get loans from the main commercial banks. Such people must often resort to riskier loans with higher interest rates. According to the report, the average monthly income of people preparing for their career is 750,000 won (US$695), while their average expenditures, including savings, are 940,000 won (US$875), leaving an average deficit of 190,000 won (US$175). Their average debt was 8.31 million won (US$7,700), which included 3.33 million won (US$3,100) from overdraft lines of credit and 570,000 won from credit cards, in addition to 4.41 million won (US$4,100)from public institutions such as KOSAF.

“The reality in Korean society is that young people who don’t have their family’s help have to take out debt to cover their university tuition and living expenses. They are forced to start looking for a job with the psychological pressure brought by debt, which means they can’t afford to be picky about job offers or to consider whether a given job is right for them,” said a full-time activist for Youth Solidarity Bank “Todak” who uses the pseudonym of “Ska.”

Debt piles up before in the blink of an eye

The debt that is initially accrued through student loans expands into other kinds of loans. According to the report, average student loans right after university graduation (between 25-29 years of age) accounted for 79.6% of the total debt, but this share dropped to 32.2% in those between 30-34 years old. In contrast, secured loans increased to more than half of the total, or 51.9%, and unsecured loans to 6.9%.

“Government statistics show that debt among the youth is increasing more rapidly than in other age groups, and they are also finding less reputable sources for their loans, including private lenders, criminals and scam artists,” said Han Yeong-seop, director of My Wallet Institute.

Lee Su-hyeok (37, not his real name), who is a regular worker at an NGO in Seoul, said that his debt had gradually increased as a natural consequence of his lifestyle. After getting a job, he paid back 18 million won (US$16,700) of his 25 million won (US$23,300) student loan, but after he went to graduate school, he started using an overdraft line of credit to cover his living expenses and ended up racking up 7 million won (US$6,500) of additional debt.

Before getting married in early March, Lee took out another 21 million won (US$19,500) through the government’s loan program for supporting newlyweds and young people by covering the housing deposit and rent on his new house. “I’m using about half of my monthly salary of 2 million won (US$1,860) on living expenses and almost all the other half to pay off my debt. I managed to get married, but I don’t think that having children or raising them will be an option,” he said.

“Young people spending more time transitioning to the workforce ultimately means that they’re spending more time with money going out but not coming in. That’s the primary reason that housing and other living expenses are leading to loans and debt. The fundamental causes for increasing debt among the youth are the inadequacy of the social safety net and youth welfare programs, the extremely high cost of housing and career preparation, and the fact that many people are forced into jobs with low pay,” Han Yeong-seop said.

By Hwang Keum-bi, staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 4Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 546% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 6Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 7[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 8[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 9Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 10“Parental care contracts” increasingly common in South Korea