hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special Features Series: April 3 Jeju Uprising, Part II] The April 3 Exodus

Amid the Jeju Uprising in 1948, many islanders fled to Japan and mainland South Korea. Some left because they were tired of life on the island; others were whisked away from the “island of death” by their mothers or grandmothers as only children and eldest grandchildren. As the military and police’s punitive operation intensified, parents smuggled their children out to save their lives – knowing they would never see them again.

These were the beginnings of what has become known as the “April 3 Exodus.” Jeju residents risked their lives on boats across stormy waters. Life in an unfamiliar land was difficult – but at least they had escaped death. Some had siblings who remained on Jeju or scattered to live in Japan, the US, and North Korea. Even after learning of their parents’ deaths back home, they could only mourn – but not return.

Departing for Japan

Osaka’s Ikuno ward is home to a large number of Zainichi Koreans from Jeju. Communities there have held memorial services since Jan. 3, 1949, when a social association for residents of Jeju’s Daejeong township in Osaka held a “service to oppose the massacre of the people” while the devastation back home was at its height. Vessels smuggling residents to Japan traveled directly from Jeju or traveled by via of Busan and Tsushima, taking advantage of sea routes between Yamaguchi Prefecture and Kitakyushu. As maritime policing was intensified in late Oct. 1948, the vessels adopted a new course toward Minamikyushu.

The number of people being smuggled off the island increased rapidly while it was being pacified. A report called “Controlling Illegal Immigration Through Ehime Prefecture” written on Oct. 25, 1948, by Japanese troops stationed along the coast said, “People being smuggled in from Korea have been apprehended every day, with more than 300 so far.” During this period, many residents of Jeju Island were caught while trying to smuggle themselves to Ehime Province in Japan on five different occasions.

But there are no concrete statistics about how many Jeju islanders fled to Japan during the Jeju Uprising. Kim Yong-ha, the governor of the island when the uprising was winding down, said that more than 40,000 people did so, but there is no evidence to back up this claim. Some researchers say that between 5,000 and 10,000 people went to Japan.

Memories of a painful pastLee Chang-sun (86, Tokyo), who was born in Osaka, Japan, and settled in his ancestral home of Daejeong Township, Seogwipo, after Korea’s liberation, witnessed three of his friends shot and killed in 1948, when he was in the first year of middle school. “They told all the people in the village to come out. We all did so because they threatened to shoot us as communists if we didn’t. I’ll never forget what I saw that day,” said Lee, who met me in Tokyo on Jan. 14.

Lee left Jeju and stayed for a short time in Seoul before passing through Busan on his way to Japan. “My grandmother died in 1949, and I heard from a friend that she asked me not to come back to Jeju no matter what happened. It’s still painful to think I wasn’t able to give my grandmother a funeral even though I’m carrying on the family name.”

The business card I received from Won Il-dong, 59, a second-generation Korean-Japanese whom I met in Ueno, Tokyo, bears the name, “Jin Il-dong.” Won’s late father, Won Gyeong-yeon, who was born in Gimnyeong Village, Gujwa Township, Jeju, also smuggled himself to Japan to survive the massacres that were taking place on Jeju. He had been part of the student movement while studying at Jeju Agricultural School and had fled into the mountains.

Won was on the verge of being shot by a local police firing squad on a field near Mt. Halla along with ten or so others when one of the guns failed to go off. This gave him a chance to roll down into a sandpit. He was the only one of the group who survived. After that, he laid low at his aunt’s house until he was arrested by the police, where he had a few brushes with death before managing to board a blockade runner.

“When the local police constabulary came for my father, my grandmother stood in their way so that he could escape. My grandmother was arrested and subjected to awful torture before being executed. She did what she had to do to save her son, who was the only son for the third generation in a row,” Won Il-dong said. Since Won’s father could no longer live in Jeju, he boarded a blockade runner that took him to Tsushima, from which he moved on to Hakata.

Won Gyeong-yeon was arrested by the Japanese police and sent to Omura Concentration Camp. Korean-Japanese from Gimnyeong Village appealed to the authorities not to send him back to Korea, which would mean his certain death. They saved his life by scraping together 800,000 yen to create a Japanese identification card for him under the name “Jin Tae-yeong.” From then on, that was the name he went by in Japan.

Won Il-dong was born in Japan as Jin Il-dong, son of Jin Tae-yeong. “My dad felt very sorry about my grandmother and missed her very much. When the anniversary of my grandmother’s death happened to fall on a trip from Kyushu to Tokyo, he would hold the ancestral ritual on the train with alcohol, rice balls and incense he had bought,” Won Il-dong said.

While Won Il-dong’s father often told him about what had happened during the Jeju Uprising, his father never visited Jeju until the day he died, remaining in Japan. “My dad said he wanted to go home several times, but he was determined to wait until Korea was reunified. He insisted that he was not a communist and was unwilling to kowtow to the people who had killed his mother,” Won said.

Won first visited Jeju when he was over 40 years old. “From an early age, I was part of the village social club, and I grew up at home speaking the Jeju dialect. So even though I was born in Japan, I’m proud to have Jeju Island as my hometown,” he said.

Han Gyeong-ik (84, Tokyo), who was in the first year of middle school during the Jeju Uprising, still vividly recalls a boy a year older than him being shot by a firing squad and the boy’s father lying prostrate in front of the police station begging for his only son to be spared.

“How could they have slaughtered their own people like animals? I’ve never forgotten the massacres at Jeju,” said Han, who almost never talks about his experience in the uprising.

“Before I went to Japan, my ailing father hobbled with his cane all the way to the station to see me off. That was last I ever saw him,” Han said, unable to go on.

When I met Bang Jeong-ok, 81, in Kawasaki Prefecture in January, she did not bring up stories about the Jeju Uprising either. Bang had been in the third grade of elementary school when the Jeju Uprising broke out in 1948, and in May of that year she had followed her father to Mokpo. They stayed there until the spring of 1951, when they returned to Jeju. The things that she heard then were appalling.

“The mother of a friend who was two years younger than me died in a field. Her eyes were blindfolded, and members of the Northwest Youth Association told the other villagers to kill her. But that was unthinkable, and when the villagers balked at the order, the Northwest Youth Association members threatened to kill them. Left without a choice, the villagers stabbed the woman with bamboo spears while begging for her forgiveness. They all covered the incident up afterward. It was so awful it made me shudder just to hear it,” Bang said. Bang, who emigrated to Japan in 1965, refused to say anything else about the Jeju Uprising, aside from the fact that she would never forget it.

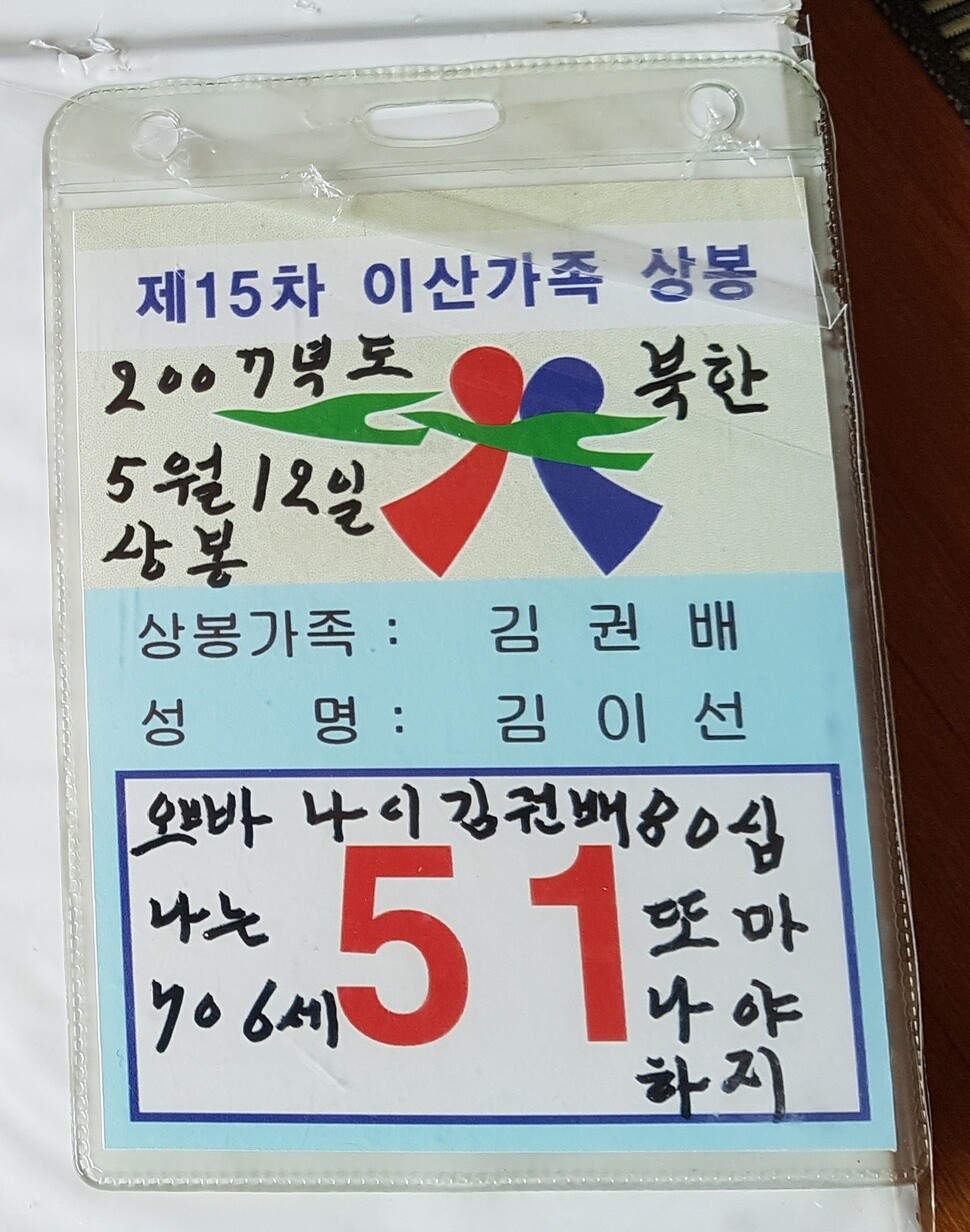

Departing for North KoreaAn unusual stone memorial stands in front of the grave of Kim I-seon’s parents in the Kim family burial plot in the Sinan neighborhood of Jocheon Township, Jeju City. The message engraved on the stone says, “The time I spent anxiously wondering whether my brother Gwon-bae was alive, the countless tears that I shed and the nights I stayed up thinking about my parents melted away like springtime snow when I met him and learned that he and his family had prospered.” This is the “siblings’ reunion stone,” which was erected by Kim (86, Jocheon Township, Jeju City) and her children just ten years ago, on Mar. 7, 2008. In 2007, Kim applied to be part of the reunions for families divided by the Korean War on the off-chance that she would learn something about her relatives. To her surprise, she informed that her older brother was alive in North Korea.

“Before we met, we promised each other not to cry because if we cried we wouldn’t be able to talk to each other. It was great just to see him alive and not dead, so why would we cry? I saw someone walking toward me and realized it was my brother. He called to me, saying ‘I-seon!’” Kim recalled.

During the 15th reunion of the divided families that was held at Mt. Kumgang on May 12, 2007, Kim I-seon met Kim Gwon-bae, 90, her second oldest brother, who lived in North Korea. Though the siblings had not seen each other since they were separated 58 years ago, at the ages of 18 and 22, they did not cry. Gwon-bae told his sister that his wife, who was from the neighboring village (Sinchon Village, Jocheon Township), had yearned for her homeland until her death just six months before the reunion and that she had been buried in a cemetery for Jeju residents in the North.

“We made five volumes of genealogy for our family and wrote down our children’s and our aunt’s children’s phone numbers at the bottom. We told them they were always welcome to come to Jeju Island and that they would not go hungry here,” said Park Yeong-seon, 64, I-seon’s son.

Many of the residents of Jeju Island who had been sent to prisons on the mainland during the Jeju Uprising were executed or went missing when the prison doors swung open during the Korean War. Some of them ended up in North Korea, not necessarily of their own volition. Gwon-bae went to North Korea during the Korean War after working for his uncle’s company in Seoul.

Gwon-bae had taught night classes after liberation in his hometown of Jocheon. He came to the attention of the police following a rally that was held on the anniversary of the Mar. 1 Movement in 1947 and had to stay in hiding, unable to return home. After being interrogated by the police about Gwon-bae’s whereabouts following the outbreak of the Jeju Uprising, his father was placed in a concentration camp at Jocheon Township and then shot dead in a field in front of the Jocheon police office on Jan. 5, 1949. Gwon-bae, who was 15 years old at the time, stayed up all night making burial clothes for his father. With his younger brother, who was nine years old, he borrowed a cart to move his father’s body to a nearby field where they dug a shallow grave and buried him.

Gwon-bae’s mother (Kim Chang-hwan, 49 at the time) had been held in the concentration camp with her husband, and she lost her life as well on Jan. 22. Gwon-bae had been living in hiding at the house of a relative in Jeju City. One day, he left for Seoul, feeling hatred for the land where his parents had died.

The last time I-seon saw her older brother Kim Im-bae (who as 29 at the time) was when he was taken to the police station for a meeting shortly after the Korean War. “At first, Im-bae was sent to the Jeju Police Department, and then he died in June. But the police didn’t tell us, so we kept sending food for him until August,” I-seon’s older sister Il-seon (94) said. It was not until later that I-seon was told that the police had put Im-bae on a boat and sailed two hours out from land, where they tied a heavy rock to him and thrown him into the ocean to drown. Since Il-seon was already married, I-seon performed the ancestral rites for her parents from the age of 16 until 70.

“I had the ‘siblings’ reunion memorial stone’ erected because I wanted to let my parents know that their son hadn’t died and was still alive and that I had met him. My brother is so hurt by our parents’ death that he won’t come to South Korea even if the country is reunified,” I-seon said. In the Kim family burial plot, the gravestones for her parents and older brother, all victims of the Jeju Uprising, bear witness to those tragic events.

Departing for the mainland

Oh Chu-ja, 80, who met me in her current home of Goyang, Gyeonggi Province, on Feb. 23, is an example of members of the Jeju diaspora who came to the mainland. In the fall of 1946, Oh and her family came to Jeju by way of Osaka and Mokpo to visit her mother’s parents, who lived in the Nohyeong neighborhood of Jeju City. The entire family came – Oh’s mother and father, her older sister, her two younger brothers and herself. “My dad went back to Japan by himself and promised to come back to get us later,” Oh said.

Oh’s father (Oh Yeong-su, who 34 years old at the time) came to Jeju to pick up his wife and children on Feb. 28, the day before the events on Mar. 1, 1947. He slept in the next morning and was having brunch when the village leader suggested that he attend a rally for the Mar. 1 Movement that was being held at the Gwandeokjeong Pavilion. After finishing his meal, Oh’s father left the house, which was the last time the family ever saw him. He was one of six civilians who were shot dead by the police after the Mar. 1 Movement rally, an incident that later triggered the Jeju Uprising.

“Not long after my dad left the house, we got word that he was dead. My mom was a total mess, bawling and telling the kids to stay in the house. The timing of my dad’s arrival was so bizarre, as if he was destined to die. He was gone before I even had a chance to say something nice to him,” Oh recalled.

Oh’s mother, who had been pregnant at the time of her husband’s death, gave birth to a son a month later, but the boy died in June 1950, when he was about four years old. Another of Oh’s brothers, six years younger than her, died around the same time. “After losing my dad, my mom would spend all day sitting on the shore and just staring out vacantly at the ocean. Her brothers couldn’t bear to see her like that so they took us all to Busan. My mom struggled to make money in Busan before moving to Seoul 66 years ago this year,” Oh said.

“We ended up going to the mainland because of the Mar. 1 Movement rally and the Jeju Uprising. The men in the village told us to leave. They said that [the killings] had happened because we had come home from Japan and that nothing would have happened if we hadn’t come home.”

Most of the people who left Jeju after the Jeju Uprising never returned. They had to carry on their difficult lives in an unfamiliar place, and they set down their roots there and built a home for themselves. But in the memories of those who left for Japan, North Korea or the mainland, Jeju always remains their homeland. The exodus from the Jeju Uprising continues today.

By Heo Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0422/1717137715201877.jpg) [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far![[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0422/1517137717613239.jpg) [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

Most viewed articles

- 1Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 2[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 3[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- 4Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors

- 5[Reporter’s notebook] Did playing favorites with US, Japan fail to earn Yoon a G7 summit invite?

- 6[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 7[Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- 8What Israel’s ‘warning shot’ response to Iran means for Middle East tensions

- 9[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 10Korea protests Japanese PM’s offering at war-linked Yasukuni Shrine