hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Expansion of EITC a pioneering step to help young people gain extra income

Kang Jae-min (27, a pseudonym) is a freelancer who writes stories for online comics, but when he runs out of work, he takes short-term gigs at events to pay the bills. If Kang makes 10 million won (US$9,300) through part-time work this year, starting next year he will be eligible to receive about 640,000 won (US$600) in earned-income tax credit (EITC), a system that provides income assistance to low-income households through tax refunds.

“While it’s not a satisfactory amount, I think it will help me gain experience as a writer and give me some breathing room by helping me cut back a little on the hectic part-time work I do to make ends meet,” Kang said.

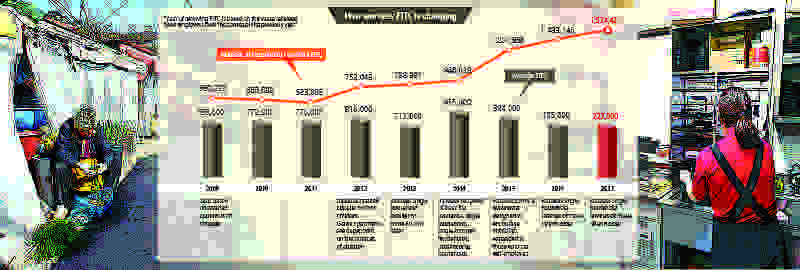

This was made possible by the government’s decision last month to eliminate the EITC age limit and extend benefits to people in their twenties living alone, which it announced as part of a youth job creation program last month. Starting next year, an estimated 157,000 young people who live by themselves will start receiving the EITC.

This is a pioneering step that greatly lowers the threshold for receiving the EITC, which was previously limited by age and household size. The government is also considering expanding the EITC to replace “job stability funding,” a measure currently in place to make things easier for small business owners pressured by a higher minimum wage. As the EITC gradually evolves toward wider applications since it was brought over from the US a decade over, attention is focusing on whether it will become a reliable “relief pitcher” that can provide wide-ranging support for low-income households.

EITC: imported from the US 10 years ago and adapted to Korean conditions

The EITC, which was first adopted in the US in 1975, was designed to help out low-income households, with the proviso that beneficiaries receive more assistance the more they work, up to a certain level of income. The system originated from the concept of “negative income tax,” which replaces public assistance, with its complicated delivery process, with an income guarantee for working families whose income does not reach a certain level.

To create an incentive for work while also supporting those in the low-income bracket, the program is based on a phase-in period, in which credit increases with income; a plateau, in which credit is constant; and a phase-out period, in which credit decreases with income. In this regard, the American and South Korean systems are largely the same.

But unlike the US, South Korea has focused on household composition rather than the number of dependent children and has sought to use the program to support people who are not eligible for the basic livelihood allowance because they are just above the poverty line. Since 2014, the government eliminated the EITC requirement for dependent children and has divided support between people living alone, single-income families and dual-income families.

Given President Moon Jae-in’s advocacy of an income-led growth model, the EITC system has received more attention since Moon took office. When the government released the new administration’s economic policy direction last year, it emphasized the need to expand the amount of payments made in South Korea’s EITC system. Around 730,000 won (US$680), these payments are minimal compared to the US (2.98 million won per household; US$2,770) and the UK (11.31 million won per household; US$10,500). On several occasions this year, South Korean Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Strategy and Finance Kim Dong-yeon has expressed his determination to treat the EITC as the basic framework for “welfare that works.”

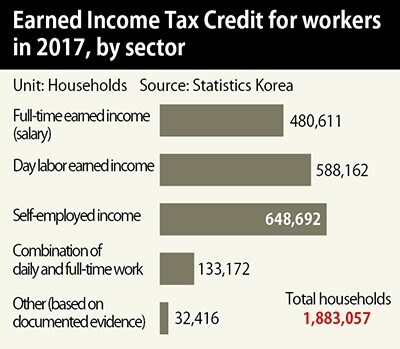

A radical experiment: making people in their 20s living alone eligible for supportAccording to figures provided by Statistics Korea, the EITC program paid over 1.4 trillion won (US1.3 billion) in benefits to 1,883,053 households last year. That works out to an average of 727,000 won (US$680) a year per household.

Under the current system, benefits for single-person households increase with higher income from 0 to 6 million won (this is the phase-in), receive the maximum amount of 850,000 won (US$780) between 6 and 9 million won (the plateau; US$5,600 and $8,400) and decrease with higher income from 9 to 13 million won (the phase-out; US$8,400 and $12,100).

For single-income families, the phase-in extends to 9 million won, the plateau to 12 million won and the phase-out to 21 million won (US$19,500) with maximum benefits of 2 million won (US$1,860). For dual-income families, benefits increase up to 10 million won, remain constant at the maximum of 2.5 million won from 10 to 13 million won and then decrease until 25 million won. For people living alone like Kang, the phase-in lasts until 6 million won, the plateau from 6 to 9 million and the phase-out from 9 to 13 million, with maximum benefits of 850,000 won (US$7,900).

The benefits for single-person households have been expanded in phases, starting with elderly people 60 years old and above, and this year the program will be opened for the first time to people in their thirties. The government’s decision to go a step further by reducing the age restriction and providing the EITC to people in their twenties and, in certain circumstances, even in their teens is no less than groundbreaking. This signifies that the young people among the working poor, who are expected to be fully capable of work, are officially included in the category of poor people whom the state is obliged to assist.

There has been considerable opposition to this in the past on the grounds that young people are different from other cohorts in that they are not required to take responsibility for their family’s livelihood.

“For one thing, there are in fact a large number of young people just above the poverty line who are forced to support themselves for low wages as they prepare for their career, and for another, South Korea’s EITC program has been focused more on boosting income for people just above the poverty line than about creating an incentive for work. Taking these factors into consideration, it would certainly be possible to expand the program,” said a senior official from the Ministry of Strategy and Finance. The youth expansion of the EITC program, which is expected to cost about 64 billion won (US$59.6 million) in tax expenditures a year, will be added to the tax code this year, with payments beginning next year.

Could the EITC help businesses burdened by the higher minimum wage?Since the EITC is closely linked to the government’s policy of raising the minimum wage and the system may well be overhauled, observers have their eye on recent developments. Last year, the ruling and opposition parties allocated 2.9 trillion won (US$2.7 billion) of the government’s budget to job stability funding (130,000 won a month in wages; US$115) in connection with the major increase of the minimum wage this year. Added to this allocation was the requirement for a report to be made by July 2018 on ways to replace the method of direct payments (that is, job stability funding) with the EITC or social insurance assistance measures.

The government is struggling to come up with a specific plan because of a mismatch between the groups eligible for support. Whereas job stability funding is available to all business owners with less than 30 total employees, the EITC targets a much narrower range of people. As noted above, EITC benefits are available to single-person households with less than 13 million won (US$12,100) in yearly income, single-income households with less than 21 million won ($US19,500) in yearly income and dual-income households with less than 25 million won (US$23,300) in yearly income.

As of this year, the salary of a worker receiving the minimum wage is about 18.88 million won (US$17,500), assuming 40 hours of work per household per week. That’s why the breadwinner in the majority of households that applied for benefits last year was not a full-time employee (480,611) but a day worker (588,162) or self-employed (648,692).

Other issues that may demand attention are the small size of the payments and the fact that the payments are only made once a year. This system is likely to be inadequate for supplementing the minimum wage, which is paid every month. This has prompted calls for higher payments and changing the payment interval to a monthly, or at least a quarterly, basis.

“The EITC expansion that came out of the discussion about raising the minimum wage appears to be moving toward a program that goes beyond welfare toward government intervention to promote fair wage distribution. That will require some major changes – pegging the income level to the minimum wage, resetting the payment cycle to a quarterly or monthly basis and increasing the amount of payments as well,” said Lee Won-jae, president of a non-profit research institute called LAB2050.

By Bang June-ho, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 3N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 4[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 5Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 6Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 7[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9[Cine feature] A new shift in the Korean film investment and distribution market

- 10[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady