hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Hard labor an increasing punishment for poor people unable to pay fines

“If you do something wrong, you ought to be punished, but surely they could have waited a few days for someone as sick as my brother. The dead can’t speak for themselves, but I find myself thinking how lonely and painful it must have been for my brother to be all by himself,” the man said, his voice trailing off.

On Apr. 22, Kim Gyeong-ho, 47, told the Hankyoreh about his older brother – only identified by the surname Kim – who died of a chronic condition at the age of 55 just two days after being sent to the workhouse. In Dec. 2017, the elder Kim was convicted of stealing a purse on a chair at a supermarket and fined 1.5 million won (US$1,380). As a recipient of South Korea’s basic livelihood allowance, Kim was unable to pay the fine, so he was admitted to the Seoul Detention Center, where he passed away on Apr. 15. That was the sixth day after he received surgery for heart failure.

After moving up from Daegu over two decades ago, Kim did a number of jobs as a day laborer and sometimes lived on the streets. He had always lived alone in Seoul, without getting married or having any children. In a room barely long enough to lie down in, he cooked his meals on a portable stove on the floor and slept under a thin blanket. The service for his old-fashioned flip phone had been cut off a long time ago, since he could not keep up with the bills. Kim’s acquaintances at the flophouse said it was basically impossible for him to pay a fine of 1.5 million won.

The reason Kim lived alone in the flophouse was because of his poor health. On Mar. 29, he had paid another visit to the emergency room. He had been having trouble breathing for nearly six months, and now he was short of breath even when he wasn’t moving. The doctors diagnosed him with fluid in the lungs and heart failure and recommended that he have an operation. But Kim asked to be discharged since he could not afford the hospital bill.

Taking pity on Kim’s situation, the doctor in charge told the hospital that the operation was necessary for Kim, and the hospital gave Kim the good news that he was eligible for an emergency subsidy as a recipient of the basic livelihood allowance. With the help of the local government office, Kim received the operation with an emergency subsidy of 1 million won (US$930) from the city, but this was not enough to cover both the operation and hospitalization. After the operation, Kim used the subsidy to make a payment on his expenses and was discharged from the hospital on Apr. 9. The doctor said that Kim needed to remain in the hospital a few more days, but he could not force Kim to remain.

At 10 am on Apr. 13, four days after leaving the hospital, Kim was taken to the Seoul Detention Center. He was there to do hard labor, since he could not pay his fine. And then at 8:45 am on Apr. 15, just two days later, he was transported to a hospital in Anyang, Gyeonggi Province, where he was pronounced dead just over an hour later. The coroner determined that his cause of death was acute heart failure.

Indigent must do hard labor alongside regular convicts

Current South Korean law dictates that people who are unable to pay a fine must make up the difference with hard labor. People who are sent to the workhouse under this system do hard labor alongside regular convicts. There are over 350 workhouses at more than 50 correctional facilities around the country at which a variety of work is done, including sewing and carpentry.

There are more than 40,000 people a year like Kim who are forced to do hard labor because they are unable to pay a fine. Figures from the Ministry of Justice show this number is on the rise: over 35,700 in 2013, over 37,600 in 2014, over 42,600 in 2015 and over 42,600 in 2016. This implies that polarization is worsening and that an increasing number of people are too poor to pay their fines, just like Kim.

“The first news I heard about my brother in 10 years was that he had died,” said Kim’s devastated younger brother Gyeong-ho, who spoke with the Hankyoreh at the flophouse in Seoul’s Jongno District where Kim had lived. The two brothers were the seventh and eighth of eight siblings. The brothers, who were eight years apart, had parted ways long ago because of their difficult financial circumstances. They had grown up together in Daegu but drifted apart after Kim left the city in search of work.

“Please use this money for my funeral expenses”

The last memory that Gyeong-ho has of his older brother is seeing him walking away from Yeongdeungpo Station 10 years ago, carrying his backpack. Gyeong-ho and an older sister had come up to Seoul to meet Kim after hearing that he was barely getting by as a day laborer. When they asked Kim to come down to Daegu and live with them, he handed them 3 million won (US $2,760) that he had saved up. “I’m sorry I haven’t been able to buy you a good meal or any decent clothes. If I die, please use this money for my funeral expenses,” Kim told them before departing.

After hearing about his brother’s death, Gyeong-ho made his way through the narrow alleys between the flophouses of Jongno District and found the room where his brother had lived. Everything was just as his brother had left it. The room, just over 3 square meters in size, had no sunlight, and it was dark and musty. Right outside the door was a urinal in a communal bathroom. There was an old down jacket on a clothes hanger, and empty ramen containers and soju bottles in a corner. Gyeong-ho pictured his ailing brother on the floor, drinking soju and snacking on the ramen noodles.

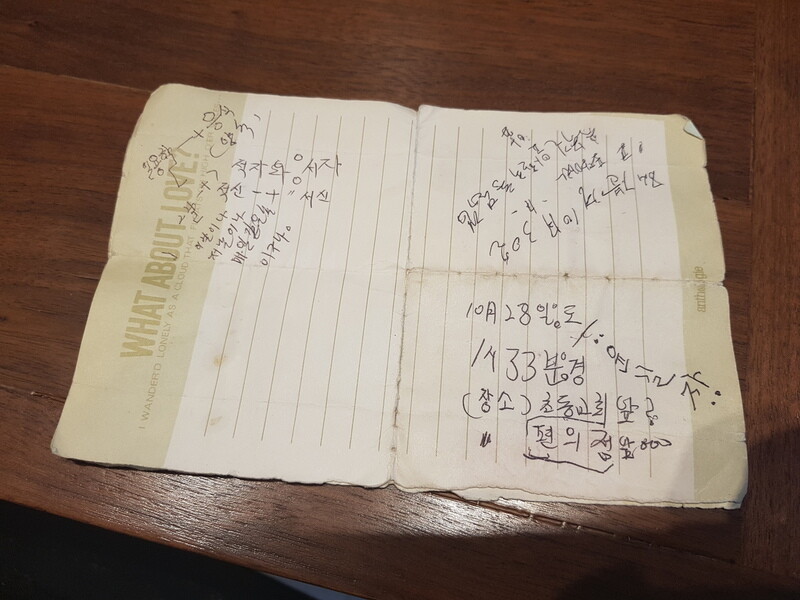

A number of notes, apparently in Kim’s handwriting, were scribbled on a scrap of paper: “Our daily bread” and “One day or another, every one is the same.” Gyeong-ho said that was the first time he had felt bitterness toward his parents and his brother. “I figured he was doing well even if he didn’t get in touch, and it made me cry to think he had cut off contact for this kind of life. That was the first time I felt aggrieved toward my own parents. That old saying that it’s a crime to be poor really hit home,” he said. The only belongings that Kim left behind was the old flip phone that had been disconnected because of unpaid bills and 14,100 won (US$12), the only money to his name.

Kim’s neighbors at the flophouse told the Hankyoreh that they remembered him as a “courteous person.” An elderly neighbor said he had sometimes had a drink with Kim. “He was always polite to his neighbors. Even when he was feeling sick, he wouldn’t show it,” the neighbor said.

“He didn’t have any money, but he picked up cardboard boxes and worked hard so that he wouldn’t be beholden to anyone,” said a 60-year-old resident surnamed Yang.

Kim had apparently reported his poor health even before he was taken to the detention center. A physical condition statement that Kim had composed at the time of his arrest and detention stated that he had been hospitalized and treated after collapsing because of a cardiovascular condition in March and that it was hard to move around because of pain in his head and chest resulting from his chronic condition. But the prosecutors and detention center staff who had sent Kim to the workhouse only stated that they had acted in accordance with the law and principles.

These circumstances do not make much sense to Gyeong-ho: “I went to the hospital to check on my brother’s body. There I learned that he had received an operation a few days before and was given the autopsy results, which said he had died because his chronic condition had gotten worse. Since it was just a few days after he was released from the hospital, he must not have had time to get better,” he said.

Gyeong-ho is taking a break from work. While he too is a day laborer who lives hand to mouth, he says he just can’t focus on his work. What he wants is to receive an apology on behalf of his brother and to prevent this kind of thing from happening to people who are placed in a similar position.

By Shin Min-jung and Jang Su-gyung, staff reporters

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 4[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 5[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 6Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 9[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 10US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters