hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Study reveals acute psychological distress among Cheonan survivors

“I just get wasted and swallow a handful of sleeping pills,” said Staff Sergeant Chung Ju-hyeon, 28, in a nonchalant tone of voice. Ever since the events of Mar. 26, 2010, Jeong has teetered on the boundary between life and death. And Chung isn’t the only one.

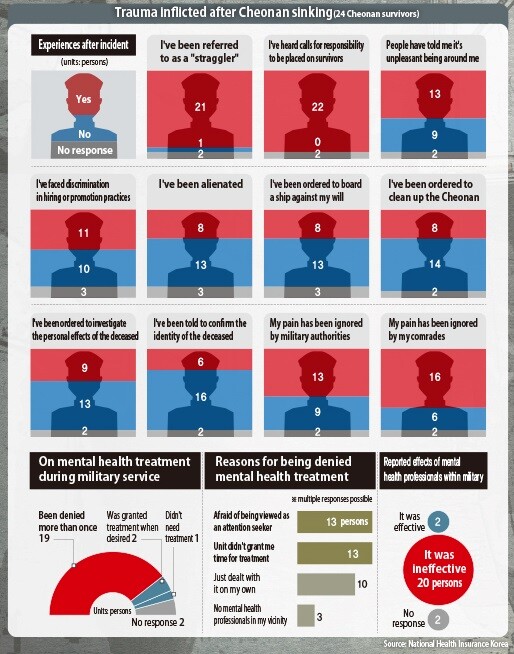

Last month, a fact-finding study about the health and social experience of the survivors of the sinking of the Cheonan corvette was jointly carried out by The Hankyoreh, the Hankyoreh 21 weekly and a research team led by Kim Seung-seop and Yun Jae-hong, professors at the College of Health Science at Korea University. Half of the survivors who participated in the study – 12 out of 24 – said they had given serious thought to suicide over the past year. A quarter of the sample (6 out of 24) said they had actually tried to kill themselves.

“Those are horrendous figures,” said Kim, after confirming the results, and then remained silent for some time. The figures were so extreme as to verge on the incredible for a man who had researched all kinds of suffering groups in South Korean society, including the people laid off by Ssangyong Motor, firefighters and sexual minorities.

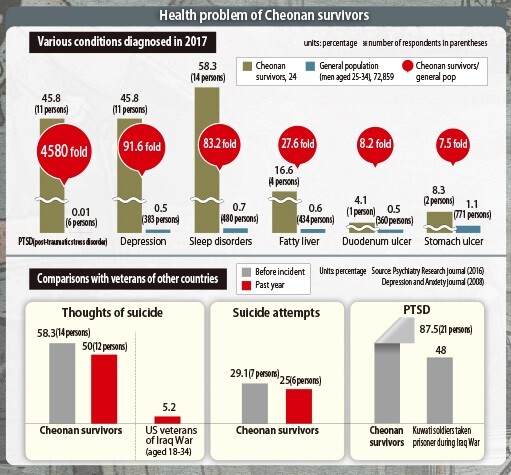

It was hard to even find anything comparable to the “weight of pain” that these numbers conveyed. Even those had been on the battlefield, with bullets and bombs falling all around them, had not been as close to death as the crew members who survived the sinking of the Cheonan. When the US National Center for PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) conducted a 2010 survey asking American soldiers (between the ages of 18 and 34) who had fought in the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars whether they had thought about suicide in the past year, just 5.2 percent responded in the affirmative. A survey of South Korean men in the general population with a similar age (25–34) to the Cheonan survivors (South Korea’s National Health and Nutrition Survey, 2013–2015) found that 3.1 percent had thought about suicide and that 0.1 percent had attempted it.

”That night, the beautiful sea vanished”

“The 2nd Fleet’s area [the Yellow Sea] is so beautiful. In the evening, the moon is bright, and there are so many stars out, which glimmer in the water. There are so many shooting stars, and you can see each of the constellations, too,” said Staff Sergeant Ham Eun-hyeok, 29. Ham had loved the Yellow Sea – but that night, the beautiful sea vanished. With the blast of an explosion, the ship rapidly began to tilt and the lights went out on the ship. Nothing was visible in the blackout.

The surviving crew members – who had to fumble through the darkness to get off the sinking ship – were injured in body and broken in spirit. Another figure, 87.5 percent, illustrates the suffering they faced and still face today: the percentage (21 out of 24) of the survivors in the study who have been diagnosed or treated for PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), which refers to the psychological reaction to experiencing the severe stress of being in a life-threatening situation.

Levels of PTSD higher than soldiers taken prisoner by enemy forces

That figure is nearly twice that of soldiers who were taken prisoner by the enemy on the battlefield. When a team of Kuwaiti researchers studied 50 Kuwaiti soldiers who had been captured during the Gulf War (1990–1991) and freed afterward, they found that 48 percent were suffering from PTSD. A survey of 103,788 American soldiers who participated in the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars found that 13 percent, or 13,205, had been treated or diagnosed with PTSD. In effect, the emotional damage suffered by the survivors was greater and more profound than soldiers who were captured by the enemy and barely returned alive.

The survivors’ pain continues today. Of the 24 in the survey, 11 said they had been diagnosed or treated with PTSD last year, while two declined to answer. In other words, nearly half of the survivors in the survey have been unable to move beyond that day’s pain and are still suffering its aftereffects.

After surviving the sinking of the Cheonan, Ham started having epileptic symptoms. When he is relaxing or by himself after work, his arms and legs clench, his eyes lose focus, and his tongue curls up. The terror he felt on the ship led to panic attacks and claustrophobia.

“Because of my panic disorder, when I board a bus, ship or plane, the first thing I look for is the exit. My biggest concern is how to survive if there’s an accident. I hated this situation so much that I told the doctor about it, but he said it can’t be fixed completely. All I can do is take medication to gradually mitigate the symptoms,” said Staff Sergeant Kong Chang-pyo, 30, his voice trailing off.

Chung is unable to get on an elevator. He can’t stand being in a confined space without a way out. He’s also afraid of the cold. He escaped from the ship in short sleeves and thin pants, and his body still remembers the frigid temperature of the ocean on that March night. He also suffers from hallucinations, with deceased members of the crew appearing before his eyes. “I have no idea why they come to me,” Chung said. He struggled to get the words out and covered his contorted face with his hands.

Lack of psychiatric help leading to self-medication

Since the crew members were unable to receive any decent psychiatric therapy, they had no decent options for overcoming their pain and terror. So they started to drink. During the days after the sinking, Kong was only able to get to sleep at night by drinking a 1.6l pitcher glass of beer. Just as he had no one to share his sorrow, he had no drinking buddy. Chung drank alone, in just the same way. He said he picked up his drinking habit after the ship sank. Every day after he finished his duties and changed out of his uniform, he would drink a pitcher glass of beer, spiked with two bottles of soju, a distilled spirit.

Ham said he used to drink five bottles of soju diluted with beer every day. When the next day was the weekend, his boozing would go on even longer. Ham always kept sleeping pills next to him. Four (16.6 percent) of the survivors said they had been diagnosed with fatty liver the previous year, a diagnosis received by just 0.6 percent of similarly aged men (25–34 years old) in the general population.

Attention given only when politically convenient

Eight years have passed since then. If even a single person had reached out to the survivors during that time, their situation might have been different. But they only got the attention of politicians and the press when the sinking’s anniversary rolled around in March. When Chung met The Hankyoreh last month, he asked why reporters had come to see him in June.

Staff Sergeant Lee Yeon-gyu, 30, put it this way: “Every March, the month the Cheonan was sunk, a lot of politicians would come to see us. We assumed they would speak on our behalf. But after the pictures they took with us went to press, they didn’t visit us again. At first we were grateful, but not anymore.”

Some comments cut like a razor – “it must be great to get compensation,” for example. Even though the survivors have not received a single penny from the state, they constantly got the same question not only from the press but also by friends and relatives.

“Some friends even asked whether I had started a business with all the money I must have gotten from the government. I didn’t say anything in response since contradicting them would just hurt our relationship,” Kong said. It wasn’t intentional, but this became a yardstick that divided the people he could meet and the people he couldn’t.

The presidency has changed hands twice since the Cheonan went down. There were the conservative administrations of Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye, and now a year and two months have passed since Moon Jae-in became president. Kim Yun-il, 30, was disappointed that the president didn’t come to the first memorial service after coming to power.

“President Moon didn’t come to the memorial service this past March. I know that the presidency isn’t a job where personal preferences determine whether or not you go to events, but it still hurt. I hope he comes next year. I hope he says that we haven’t been forgotten,” Kim said.

The survivors live on like restless spirits, with no one to bring them consolation. Writing off their pain as some kind of victim mentality might be violence of another kind.

“The conservatives were just exploiting us. The progressives? They didn’t even come to see us,” said Sergeant Choe Gwang-su, 30, who went into virtual exile in France, unable to live under the “scarlet letter” of the Cheonan.

“I just didn’t see any way I could go on living in Korea,” Choe confessed.

Abandoned by all and left on their own, these men have held on for eight years, as their afflicted bodies and souls cry out for help.

By Jung Hwan-bong, Choi Min-young and Byun Ji-min, staff reporters

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 3No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 4Samsung subcontractor worker commits suicide from work stress

- 5[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 6Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 7N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 8Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 9Flying “new right” flag, Korea’s Yoon Suk-yeol charges toward ideological rule

- 10[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol