hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special feature] The myth of ‘glamorous singles’, most of them “economically vulnerable”

The sweet sound of jazz fills the air.

The celebrity wakes up in a dark room, but the screen brightens when he/she pulls back the curtains. The window offers a fine view of downtown Seoul. The celebrity feeds his/her pet, which is already up and moving around the house. A flashy imported car awaits in the underground parking garage. Long after the morning rush hour has passed, the spotlighted celebrity cruises through the empty streets of downtown, lost in thought.

This is a frequent sequence shown on “I Live Alone,” a variety show that has been broadcast on MBC since 2013. The producers of the show have described their goal as “building a social consensus since single-person households are the current trend.”

But what viewers see on “I Live Alone” is a far cry from the reality of the five million people who live alone in South Korea today. According to Statistics Korea’s 2015 Family Finance and Welfare Survey, 50.6% of single-person households have less than 12 million won (US$10,621) in yearly income. The “Poverty Statistics Yearbook” published by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) reported a relative poverty rate of 45.7% for single-person households in 2016, based on their disposable income.

That’s much higher than the relative poverty rate of 13.8% for households of multiple people. The relative poverty rate refers to the share of households whose income is no more than half of the median income (that is, the income of the middle household, if all households were lined up by income). The higher the relative poverty rate, the more severe the poverty of the affected group.

The gap between “I Live Alone” and average single-person households

The majority of people in single-person households aren’t “glamorous singles,” but “economically vulnerable.” The daily lives of celebrities seen on “I Live Alone” fail to reflect the actual conditions of single-person households today, which is why the show has also failed to “build a social consensus.”

Single-person households are poorer than multi-person households where families live together. When the National Assembly Budget Office estimated the household income per family member in 2016, it found that the equivalized income for single-person households was 1.7 million won (US$1,500), which was much less than the equivalized income for multi-family households of 2.5 million won (US$2,213). Equivalized income is a figure that converts a household’s income to the income of household members in order to compare the income of households of different sizes.

The equivalized income of single-person households at least 70 years old was 950,000 won (US$840), not even reaching the 1 million won (US$885) mark. It’s only among single-person households in their 30s (2.66 million won [US$2,354]) where income exceeds that of multi-family households (1.95 million won [US$1,725]). The lifestyle of the “glamorous singles” depicted in “I Live Alone” corresponds to a few of the highest earning even among those in their 30s.

The number of single-person households continues to increase and is expected to reach 7.6 million by 2035, at which point it will represent 34.3% of all households. Experts and academics agree that aid programs should be developed that are tailored to the evolving and diverging characteristics of single-person households (age, residence, marital status, gender and so on).

The bracket that demands the most attention from the community and support from the government is elderly single-person households, composed of individuals in their 60s and above. As the average lifespan has increased, one out of three single-person households fall in this age group. Amid the weakening of traditional family values, including the norm that people should provide for their aging parents, many single-person households in their sixties and above were left alone when their spouse passed away. Statistics show that 49.2% of single-person households in their 60s and 86.9% in their 70s are the result of spousal bereavement.

80% of single-person households in 70s and above are elderly women

The average lifespan of women (86.17 years in 2015) is longer than that of men (78.98 years), resulting in a large number of elderly women in single-person households. As of 2015, 80.4% of single-person households in their 70s or above consisted of women. Female elderly single-person households are vulnerable in each of those three respects (female, elderly and single-person household), and they also face the triple threat of social isolation, unstable housing and poverty, and health problems such as dementia and chronic disease.

Elderly women who have spent their lives under the traditional social structure and labor market are likely to depend on “transferred income” in the form of pension or inheritance from their deceased spouses rather than their own work income. In her paper “Current Conditions of Elderly Women in Single-Person Households and Policy Remedies,” Song Yeong-sin, president of the Senior Hope Community, called for government aid based on the three pillars of economy, healthy and society.

Song elaborates her argument as follows: “There also needs to be a revision of the national pension system, which was originally devised on the assumption that the man is the breadwinner and the woman is a dependent. More women have to be admitted into the labor market to increase the national pension service’s coverage of elderly women in single-person households.

Aid programs for elderly jobs also need to be made more accessible for elderly women in single-person households. It’s easy for such women to become marginalized, so support should be given to various forms of collective living arrangements, as advanced welfare states do, so that these women can form and support social networks.”

Even single-person households in their 30s – the only age cohort in which single-person households have higher equivalized income than multi-person households – can’t be defined as “happy and glamorous singles.” There’s a considerable income gap even in this age group, and many of them face poor housing conditions.

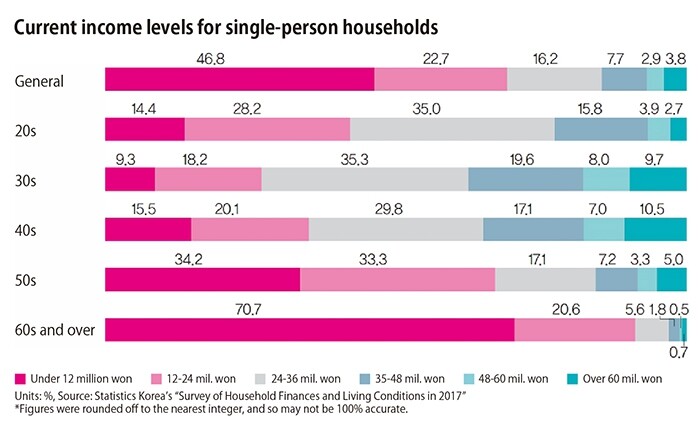

According to data from Statistics Korea, 9.7% of single-person households in their 30s have a yearly income above 60 million won (US$53,107), while 9.3% make less than 12 million won (US$10,621) a year. While elderly single-person households are universally impoverished, there’s a distinct gap between the rich and poor among people in their 30s. Young people in their 30s are more likely to live near Seoul or other urban areas than other age groups. When young people with little income live in an urban area, they have to put up with worse housing, while paying more than they would in other areas. People facing poor housing conditions can hardly expect a high level of safety.

Higher crime rates in areas with high concentrations of single-person households

Female single-person households in their 30s feel more anxiety about being the victims of crime than other cohorts. A recent analysis by the Korea Institute of Criminology found that neighborhoods with a high concentration of single-person households have a crime incidence rate that is two or three times higher than areas with fewer single-person households. Women in their 30s who live in studio apartments on lower floors are so afraid of peeping toms that they’re reluctant to open their windows, even in the middle of the summer.

The fear felt by such women is amply illustrated by the tendency to feign a male name when ordering items online or to have a father or another male family member call to arrange a water heater repair in order to conceal the fact that a woman is living alone.

So even though people in their thirties make more money than other age groups, they face a more severe income gap, and women living alone are terrified of being the victims of crime. Therefore, these generational characteristics should be taken into account in creating a social safety net.

Death by loneliness

More recently, middle-aged single-person households (people between the ages of 45 and 64) have been recognized as being neglected by welfare. A 2016 report on the current status of “godoksa” (literally, “death by loneliness”) in Seoul and on aid programs found that the middle-aged accounted for the highest percentage, at 62%, of the total cases of lonely deaths. People in their 50s accounted for 35.8% of these deaths. Overall, men made up 84% of lonely deaths, greatly outnumbering women.

Strictly in terms of lonely deaths, male single-person households in their 50s are the cohort that’s the most at risk. This is a population group that has begun to leave the workforce and that lacks social support when marital discord leads to divorce or breakdown of the family. When such troubles are combined with illnesses, analysts say, men are placed in even greater danger.

Elderly women, poor living conditions for people in their 30s, and a high risk of a lonely death for the middle-aged – this is the harsh reality of single-person households in South Korean society .

There’s an urgent need for single-person household policies that are customized for different generations and groups. The community needs to open its eyes to the reality that lies hidden behind the glitzy single lifestyle depicted by “I Live Alone.” All of us either were, are or will be single-person households one day.

By Lee Jae-ho, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 3Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 4[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 5Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 6[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 7Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 10‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis