hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

The heartbreaking tale of the slaughter of Donggwang villagers at Jeongbang Waterfall

Jan. 27, 1949, was a warm day, at least for winter. Bok-sun, who was 12 years old at the time, and her eight-year-old brother Bok-nam cried as they ran after their father (Kim I-su) and mother (Bak Sun-yeo). The family had been held at a concentration camp near the government office in Seogwipo Township, and now their parents were being taken somewhere else.

They had cold rice balls in their hands. When Bok-nam wailed, soldiers shouted for him to be quiet, and one struck the boy with the butt of his rifle. Blood gushed from the boy’s left eye. Bok-sun held her bleeding brother in her arms and cried bitterly. Not long afterward, the trauma from the blow caused Bok-nam to go blind.

“Dad handed his rice ball to Bok-nam and said, ‘What’s the point of us eating these when we’re just going to be killed anyway?’ I clung to my mother and told her, ‘Let me go with you, Mom. If you have to die, I want to die, too.’ Mom said, ‘You’ll be all right, so just do as I say,’ and gave me her rice ball. That was the last thing [she said].”

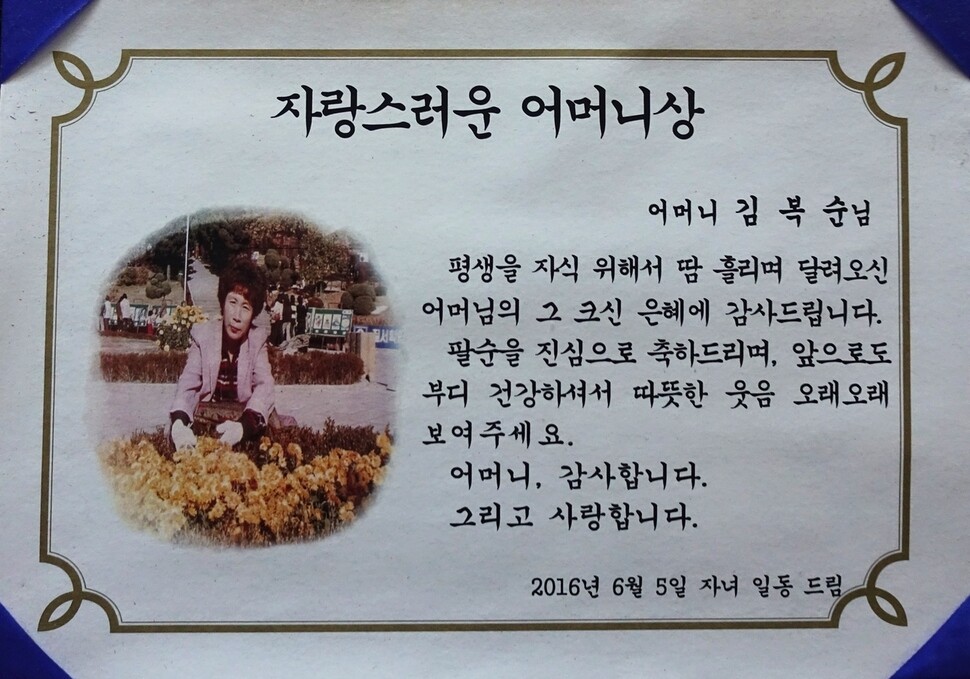

Kim Bok-sun, 82, lives in the Seohong neighborhood of Seogwipo Township, on Jeju Island, and she still has a vivid recollection of the last time she saw her parents, 69 years ago. “When I walk down that way, I sometimes see my parents giving us their rice balls and being taken away toward Jeongbang Waterfall as if it were yesterday.”

Kim’s father folded the cotton overcoat he was wearing and handed it to his daughter. “Go have someone convert this into a pair of pants or something that you can wear,” he said. “That was the first overcoat that Mom made for Dad with their meager resources, and Dad gave it to me when he was being taken away to be killed,” Kim said.

Villagers held at concentration camp before being executed

The villagers who had been held in detention were taken to the area around Jeongbang Waterfall. At that time, there was a regimental headquarters at the Seogwipo Township office that hosted the 1st battalion of the 2nd regiment, and the starch factory located where Seobok Gallery is today had been converted into a concentration camp. The seashore near the waterfall was frequently used for firing squad executions between Nov. 1948 and Jan. 1949.

According to “In Search of Lost Villages” (published in 1998 by the Academic and Cultural Project Promotion Committee on the 50th Anniversary of the Apr. 3 Jeju Uprising), 45 of the residents of Donggwang Village (where Kim and her family were living) were shot and killed near that waterfall.

Kim’s parents had been born in Yeongam, in South Jeolla Province. They moved to Jeju Island in 1940, when Kim was three years old, and her younger brother was born the same year. Kim’s father worked as a foreman on construction sites on the island until he got in an accident and had to use a cane. At the time of the Jeju Uprising, the Kim family lived in Josugwe, a hamlet in Dongwang Village, Andeok Township, on the sparsely inhabited the mid-altitude region leading up to Mt. Halla. There were just over ten families in Josugwe. It was not far from Mudeungiwat Village, which was burned down by government troops sent to pacify the uprising.

Kim’s parents were so poor they had a hard time keeping their four children fed. Somewhat earlier, Kim’s parents had sent her sister Bok-rye, who was four years older than Kim, to the township of Hallim, in Jeju City, to be adopted by a family there. The oldest child in the family was Bok-yong, but he was detained during the uprising at the age of 17 and sent to Jeju Prison, where he died of disease.

Fleeing home and hiding out in a cave

In mid-Nov. 1948, the families at Josugwe were forced to leave by the troops, who proceeded to burn down the hamlet. Without any connections on the island, the Kim family followed the other villagers to a natural cave in Donggwang called Keunneolpgwe, where they hid themselves. The oldest son, Bok-yong, had already gone to Mudeungiwat Village, where his friends lived, which left the parents with their two youngest children.

“We would stay in the cave until nightfall, when Mom and I would crawl out and return to our burned-out house. We would start a fire and either prepare some food to eat on the spot or boil some barley and carry it back to the cave in a big basket,” Kim said.

After living in the cave for a while, the Kim family packed their things and went deeper into the woods. A rumor was going around that the cave had been discovered and that the military would soon be launching an attack. The villagers left the cave in the middle of the night and made their way through snow drifts that came up as high as the adults’ knees toward Bolle Oreum (a parasitic volcano) near Yeongsil on Mt. Halla, more than 1,300m above sea level.

“We followed the villagers up [the mountain] after hearing that the military were on their way. We just wanted to stay alive one more day. Holding his cane, my father helped my mother keep going, while my brother and I waded through the snow behind them.”

The villagers walked up the snow-covered slopes all night and got fairly high up on the mountain, but within a few hours, they were caught by the military that were tracking them. “I felt so cold and so tired I just wanted to get under the blankets, and then I heard the crack of gunfire. It was morning, and the sun was shining brightly in the sky. They took us all the way to seaside Jungmun Village, and armed soldiers in the front and rear would savagely beat anyone who fell behind from exhaustion.”

While Kim was hiding in the cave, she witnessed an older couple abandoning a newborn baby. “When I was peeking out from under the blanket early in the morning, I saw a woman go outside carrying a straw mat. After a while, she returned with blood on her clothing. I heard people whispering that she had just had a baby. Nobody said a word to that couple.”

After being taken to Jungmun Village, the Donggwang villagers were once again moved to a concentration camp near the Seogwipo Township office. The concentration camp was near the top of Jeongbang Waterfall. Kim’s younger brother Bok-nam, now deceased, described his experience in detail to the Jeju Provincial Assembly, which prepared a report in 1996 about the harm caused during the Jeju Uprising:

“We spent the night in Jungmun, and they would call the adults over and beat them half to death, until their heads were caked in blood. Even after going [to Seogwipo Township], they would have the adults come in one at a time and beat them severely. On the third day there, they asked everyone who wanted their children spared to raise their hands. My father raised his hand, and over half of the people who were there raised their hands as well. There were also a lot of families who all wanted to die together. That morning, they lined up 86 adults and children carrying their last rice balls next to Jeongbang Waterfall… I saw it as plain as day. The ground near the waterfall was strewn with corpses.”

Kim also witnessed her parents’ death, though from a distance. “I stepped out of the warehouse they were using as the concentration camp because it was nice and warm, and then I heard a murmur from the crowd. One woman said to me, ‘Hey, look over where the sun is coming up. They’re killing your mother and father. They’ve put them in a line and are gunning them down.’ There weren’t any houses or big trees in that direction, so I saw it all. There was a rattle of gunfire and a line of people fell to the ground, and I could only weep at the thought that Mom and Dad were dying.”

Life as a “rebel brat”

Kim didn’t have the luxury to even look for her parents’ bodies. The bigger problem was how she and her brother were supposed to survive in the future. After staying at the concentration camp for a month or so more, Bok-nam went to Gangjeong Village, while Kim worked as a servant in Seogwipo Township until she was adopted by a family in Hallim. While Kim was living in Seogwipo Township, she saw her older brother Bok-yong carrying stones while she was on her way back from washing clothes at Cheonjinyeon Waterfall, and even now it eats at her that she had to pass him by without speaking because of the people around her.

Since she was working as a servant and was known as a “rebel brat,” she couldn’t work up the courage to say a single word to her brother when she saw him. She later heard from one of her brother’s friends that he had come down with a fatal case of dysentery when he had nearly completed his sentence at Gwangju Prison.

In 1952, Kim boarded a ship bound for Busan with the vague hope of finding her older sister Bok-rye, who had gone to the mainland. Kim was 15 years old at the time. After that, she moved around the country before coming back to Jeju at the age of 25, where she found her younger brother. Kim and Bok-nam were dramatically reunited with Bok-rye in the early 1980s, 30 years later, when TV stations ran programs to help divided families locate each other. But both of Kim’s siblings have since passed away, leaving her alone.

On Apr. 11, 2015, Kim attended a shamanistic ritual organized by the Jeju People’s Artist Federation at Seobok Gallery – the very place her parents were shot – but she was overcome by grief and wailed bitterly. “I kept thinking to myself, this is where Mom and Dad were killed, and that’s where my parents gave us their rice balls,” she said.

“Even now, I find myself crying when I think of my parents at night. There are times when my pillow is soaked through with tears. But as I’ve gotten older, my memories from that time have gradually faded,” Kim said. Kim points out of her apartment window at the place where she and her family were taken down the mountain by the government troops.

By Huh Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 346% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 4Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 5‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9“Parental care contracts” increasingly common in South Korea

- 10[Interview] Dear Korean men, It’s OK to admit you’re not always strong