hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Socioeconomic polarization plays significant role in declining birth rate, study finds

Socioeconomic polarization in income and employment is a larger factor in South Korea’s low birth rate than the trend of couples marrying late or remaining unmarried, empirical research findings show.

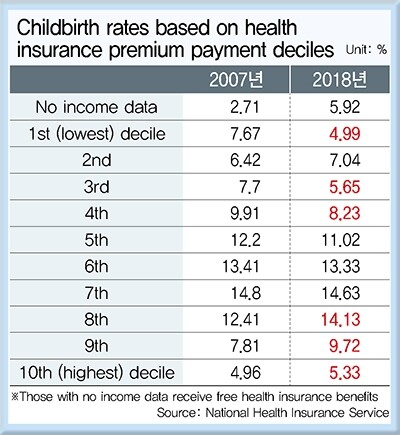

A report on “Current Low Birth Rate Indicators and Their Implications” published on June 4 by the National Assembly Research Service (NARS) also showed the percentage of married persons in their 30s and 30s increasing as wages rose. The data further showed clear differences in marriage and childbirth patterns for different income brackets, with a lower percentage of couples having children at low income levels and a higher percentage at high income levels. An examination of childbirth rates based on health insurance premium payment deciles (categorizing payments for all households according to income bracket) over the 12-year period from 2007 and 2018 as provided by the National Health Insurance Service (NIS) showed a trend of lower percentages for lower incomes and higher percentages for higher incomes.

The childbirth rate for the first decile – representing the lowest-earning 10% – decreased from 7.67% in 2007 to 5.92% in 2018. The rate rose slightly from 6.42% to 7.04% for the second decile, but fell from 7.7% to 5.65% for the third. In contrast, the period from 2007 to 2018 saw rates increasing from 12.41% to 14.13% for the eighth decile (incomes falling in the top 20–30%), 7.81% to 9.72% for the ninth decile (10–20%), and 4.96% to 5.33% for the highest-earning tenth decile (0–10%). Total childbirths declined for nearly every decile regardless of income.

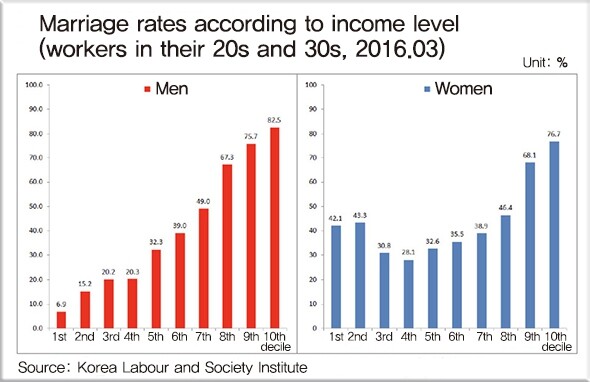

The percentage of marriages also rose with higher income levels. According to an analysis by the Korea Labour and Society Institute (KLSI), 6.9% of male wage earners aged 20–39 who ranked in the lowest-earning first decile (based on monthly wages for the salaried worker population) were married in 2016, compared to 82.5% in the highest-earning tenth decile. The numbers indicated a difference of roughly 12 times in the marriage rate between the lowest- and highest-earning groups. Men in general were also found to exhibit higher rates of marriage at higher incomes. But marriage rates stood below 50% for the first through seventh deciles, with a 49% rate for the seventh. The rate rose sharply for subsequent deciles, with a 67.3% rate for the eighth. Among women, a trend of marriage rates rising with income was observed from the fourth decile, with a rate of 28.1% for the fourth and 76.7% for the 10th.

Based on these findings, the report concluded that “the decline in marriage and childhood is disproportionately manifested according to social stratum.”

“Social polarization is having an overlapping effect as disparities in marriage translate into childbirth disparities,” it observed. The report also noted that the phenomena of late marriage and non-marriage, which have often been cited as factors in South Korea’s low birth rate, are “no different from global trends” – meaning that they are not situations unique to South Korea that account for the world’s lowest total fertility rate. As bases for this, the report noted that the average age of 30.1 years for South Korean women marrying for the first time in 2016 was similar to the OECD average of 30 years, while the crude marriage rate (representing the number of new marriages per 1,000 people) stood at 5.5, which was higher than the OECD average of 4.8.

“A notable difference in comparison with other countries is that the lowest birth rates are found for all age groups except for the 30–39 group. This phenomenon appears to be the result of difficulties in having children due to the financial burden of childcare,” the report said.

The report concluded that an approach to reduce the practical burden in terms of childcare “must be capable of not simply providing support with the costs of child-rearing but reduce those costs themselves.”

“Job creation policies should be oriented toward increasing incomes, employment stability, and the number of suitable jobs with future prospects, while housing policies for newlywed couples should be strengthened, especially for low-income households,” it advised, signaling that a realistic solution to South Korea’s low birth rate lies in correcting socioeconomic polarization and inequality in income and jobs.

By Lee Kyung-mi, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 3Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 4[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 7No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 8The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 9[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 10Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?