hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Pastors and church workers consistently underpaid, overworked and exploited

“I want to report my ‘devotion work.’”

For a certain group of people, the labor laws that are supposed to apply to everyone are a world away – simply because their workplace happens to be a church. These are the clergy and laborers who work in South Korea’s churches. Their claims concern duties that are effectively forced on them by the church in the name of piety. People who work in the church refer to this type of labor exploitation as “devotion pay.”

Over a two-month period, the Hankyoreh heard accounts of devotion pay duties from 35 people (21 in face-to-face interviews and 14 in telephone or written interviews). The stories came from a range of jobs from assistant pastor to preacher to clerical staff. How could something like this happen in an environment that is supposed to abound with love and the Gospel?

“CCK leader treated preachers as household help”

“This is someone who claims profits for herself in the name of Jesus Christ – a wolf in sheep’s clothing.” (Preacher “K” formerly employed with Bundang Hwaetbul Church)

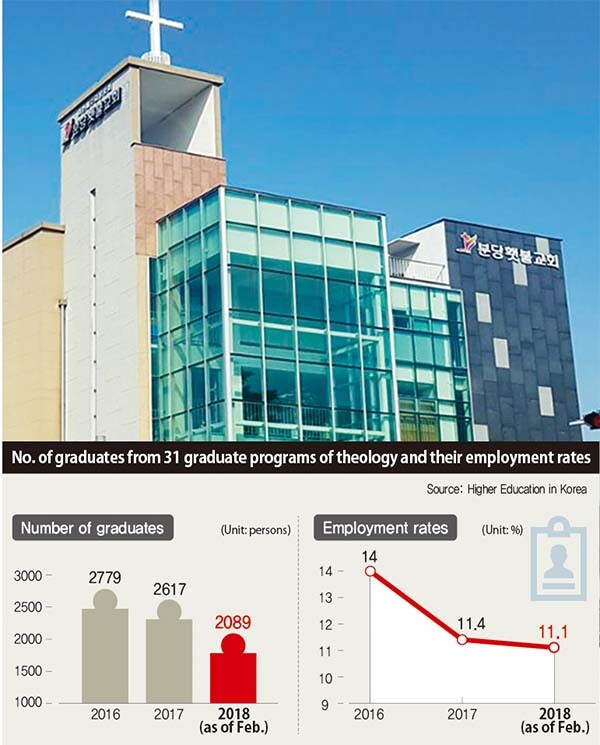

On May 7, a group of preachers, assistant pastors, and congregation members at Bundang Hwaetbul (Torchlight) Church in Seongnam, Gyeonggi Province, met with the Hankyoreh to expose the tasks unfairly assigned to them on a routine basis by head pastor Lee Jae-hee, which included having church members serve as household help for her daughter while she was studying abroad. Lee has been ministering at the church since establishing it over two decades ago (as White Stone Church); she has also held important positions in religious federations, including co-vice chairperson of the Christian Council of Korea (CCK).

For a six-year period beginning in 2010, Lee sent religious workers to Los Angeles in “shifts” of two to three at a time – ostensibly to establish a “branch” for evangelism and engage in “overseas missionary activity.” The reality was a different story: workers who were dispatched there reported living at the home of Lee’s daughter and performing household chores while she studied in LA.

“All we did was go to Rev. Lee’s daughter’s house and do chores – everything from cleaning to washing underwear,” said “H,” an assistant pastor who has paid three visits totaling around nine months to the US since 2010.

“We were basically housekeepers, and we weren’t even paid for it,” H said.

The preachers also described painting and repairing the empty church building amid blazing temperatures during the day while Lee’s daughter was at school. Additional duties included pulling weeds and cleaning up garbage left by local homeless people. Beginning in 2010, over 20 people were forced into this sort of “devotion pay” work.

Orders to do personal duties for Lee were also issued back at home. Preacher “B” worked for nine months at Company “K,” a pet placement and dog hotel business operated by Lee’s son.

“They said I’d be paid each month, but it only ever happened twice – and even then, I once paid it to Rev. Lee during the collection,” B said. Congregation members were also enlisted to tend to the sick mother of Lee’s husband.

No pay at all was provided to the preachers tasked with preparing for services, leading praise, ministering to youths in the intermediate and advanced divisions, and performing night shift duties in the office. Another preacher also identified by the initial “B” said, “The money for everything from printer paper to batteries for the microphones was all scraped together by the assistants.”

“I was having a hard time financially and even had to go into debt with a lender,” B said.

While they were aware that Lee’s orders were not justified, they had difficulty turning her down.

“If we weren’t compliant toward her, she would scold us for ‘defying the word of God,’ and she would promote an atmosphere of fear by telling us we could ‘end up damned,’” H said. “I think she thought of the congregation members and assistants not as children of God, but as her own servants.”

Since January 2019, former assistants and congregation members who left Hwaetbul Church have been denouncing Lee’s improper labor practices. When asked by the Hankyoreh for comment, Lee said the claims were “false unilateral accusations by people who left bearing a grudge toward the church and its minister.”

Carrying construction materials and farming sweet potatoes; “expendable” preachers

Hwang Myeong-joong, a 28-year-old preacher, would start his mornings organizing rebar. His daily routine involved carrying heavy construction materials. The head pastor at church “K” in North Jeolla Province, where Hwang went to minister in January 2018, told him, “We need an education center to teach the congregation.” His job was to build it; the minister called it a “necessary labor for God.”

Hwang said, “I think people can end up doing odd jobs at any workplace, but this crossed a line. After spending all day doing construction work, I never had time to prepare for sermons or worship.”

The construction work only ended around sunset. No sooner did Hwang finish dinner than another job awaited him: organizing the parishioner database. Often he would spend until after midnight starting at the monitor. For all of his work, he received 1.1 million won (US$928) a month – which translated into take-home pay of 990,000 won (US$835) after his tithe. Early this year, he finally left the church after “ministering” there for a year. The church gave him a parting gift of 100,000 won (US$84.37).

Church K was the second place where Hwang ministered. Before that, he had worked in early 2017 as a part-time preacher (typically just two to three days a week) at another church in North Jeolla Province. He discussed an arrangement with the pastor where he would work for two days over the weekend so he could focus on his studies during the week. The promise wasn’t kept; the head pastor would often summon him on weekdays. When he arrived, he was ordered to do unwanted tasks. The head pastor asked him to farm sweet potatoes to “donate to the mission field.” As he was cultivating a sweet potato field measuring 33,000m² in area, Hwang began thinking about quitting the ministry. Bruised by his experience at his first ministry, he ended up forced into “devotion pay” work at his second church.

“People serving at the church are regarded as completely expendable.”

Myeong-jung is just one of many junior pastors who have suffered “devotion pay.” They’re expected to wear a lot of different hats, doing whatever work is required of them.

A man in his 30s — let’s call him Kim Byeong-uk — was a junior pastor at a church in Seoul’s Nowon District. For seven years, Kim was in charge of nearly all the work at the church, including driving vehicles, preparing for services, preaching sermons, cleaning the building, and even running errands for the senior pastor.

“When we had services on Wednesday and Friday, I wasn’t able to wrap up my work until 10 or 12 at night,” Kim said.

Kim was only making 600,000 won (US$506.21) when he was working part time as an intern pastor and 1.2 million won (US$1,012) when he was upgraded to full time. Eventually, he realized this wasn’t enough to live on. Today, he is serving at another church while working as a mover on the side.

“Do it graciously”: employees and congregants also deal with devotion pay

“Devotion pay” is also prevalent in church organizations. A 27-year-old woman identified by the pseudonym Kim Yeo-reum was approached by a pastor at her church and asked to help run a counseling center for young people at the church. She was happy to accept, since she’d majored in counseling at college and was looking to get some more experience.

The initial plan was for Kim to work from 10 am to 6 pm, four days a week. But after a few months, her work hours increased. The pastor wanted her to work until late at night. Even when she was working more than 10 hours a day, five days a week, her only compensation was 400,000 won (US$337.47). Several times, she complained to the pastor about how hard her job was and said she wanted to quit. Each time, the pastor stressed the experience she was gaining and her religious devotion. “You’re learning, too, you know,” the pastor said. “You’re all doing this for the Lord, and the Lord will repay you.”

And so Kim continued devoting herself to the church for nearly two years, starting in early 2014. But all that devotion proved meaningless when the minister in charge of the counseling center was arrested for a sex crime. “I realized I’d wasted my time, and that I’d been exploited,” she said.

The maintenance and janitorial staff at churches often endure poor working conditions, even when they’re not technically performing religious service. That’s especially true of the maintenance staff who live in church housing and typically don’t have fixed working hours. They’re expected to show up when they get a call from the senior pastor or an elder, even on weekends or in the middle of the night.

Lee Hyeong-yeon, as we’ll call him, is a 65-year-old maintenance worker at a church in Seoul. “Even though the church is closed on Monday, the maintenance staff doesn’t usually get the day off. We have to chauffeur around the ministers when there’s a meeting of local churches. We aren’t paid anything extra for that, either,” Lee said. Because Lee lives in church housing, he isn’t given much in the way of vacation time.

The family members of maintenance workers are often frequently enlisted for service at the church. While this service is ostensibly voluntary, it’s effectively mandatory, according to those who have experienced it.

“We have to prepare meals for church services and other events, and when the dishes pile up, the ministers tell us to ‘do it graciously.’ What they mean is that we have to work. The fact that we’re living in church housing means that it’s not feasible to turn down those requests,” said the frustrated spouse of a maintenance worker at a church in Seoul.

Exhausted youth have trouble complaining about these issues

Devotion pay is present in many aspects of church life, a conclusion that’s reflected by the findings of a survey carried out by Christian website Jundosa.com (jundosa means “junior pastor”), at the Hankyoreh’s request. When Jundosa.com asked social media users whether they’d ever been hurt by devotion pay, 847, or 86%, of the people who participated in the poll said they had.

Those who responded in the affirmative were then asked what kind of situation they’d experienced, with multiple answers allowed. In this follow-up survey, 86 of 110 respondents, or 78%, said they’d had to do extra work on top of their original responsibilities; 59% said they’d been forced to show up for work outside of their normal working schedule. About one of every three respondents (34%) said they’d been mistreated by powerful people in the church (such as pastors and elders), while a similar percentage (32%) said their family members had been asked to serve against their will.

This survey also found that people serving in churches are being paid poorly. The average monthly salary of 40 people who identified themselves as full-time church workers (junior pastors, assistant pastors, and missionaries) was 1.6 million won (US$1,349); 72 of the respondents (66%) said they’d received pay that was much lower than the senior pastor.

Despite being aware that devotion pay isn’t right, exploited workers still find it hard to voice their grievances at church. A whopping 86 of the respondents (78%) said they couldn’t do anything to improve their situation. Only 18 of the respondents (16%) said they’d been able to make an official complaint. Many who said they’d experienced devotion pay were in their 30s, representing 53% of respondents. These exploited church workers said that the working situation at church should be improved by recommending changes to the denomination or revising the church bylaws (56%), by changing the attitudes of ministers (55%), and by organizing a labor union (32%).

By Park Jun-yong and Bae Ji-hyun, staff reporters

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 4Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 5[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 6Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 7[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 10Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?