hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Health insurance coverage restricted for foreign regional subscribers, local enrollment made mandatory for stays of 6 months and longer

Since August of last year, Larisa Kim, a 63-year-old second-generation Kareisky (ethnic Korean from the former Soviet Union) with Russian citizenship, has lived with her 41-year-old daughter (also surnamed Kim) in Ansan, Gyeonggi Province, while looking after her eight-year-old granddaughter. Larisa and her daughter have F-4 visas that allow them to stay in South Korea for up to three years according to the Act on the Immigration and Legal Status of Overseas Koreans; both are entitled to find employment. The daughter, who has been responsible for the family’s livelihood now that she is on her own, struggles with the Korean language and found a factory job through a dispatch agency. She makes the minimum wage at 1.74 million won (US$1,430) a month and pays 400,000 won (US$330) in rent. How did a family of three in such straitened circumstances end up with a monthly health insurance premium of 226,100 won (US$186) as of this July?

Earlier this year, the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) amended the National Health Insurance Act to require “local enrollment” (for residents of cities and farming and fishing communities who are not enrolled through their workplace) for all foreign residents (including overseas Koreans) staying in South Korea for six months or longer. In the past, eligibility for local enrollment was extended to foreign residents with sojourns of three months or longer; whether to enroll was up to the individual. While migrants not enrolled through their workplace signed up for local coverage, they were to pay either the premium amount calculated according to their income and assets or the average premium paid by all subscribers the year before (113,050 won/US$93.17 in 2019), whichever was higher.

This means that most of the residents affected – not including those with sojourn status as permanent residents (F-2) or marriage migrants (F-6) – are required to pay a monthly premium of at least 113,050 won, regardless of their income. Kim has worked at the same factory for over a year, but does not receive workplace enrollment, where the place of employment covers half of premium costs. The reason is that she is not officially regarded as having been directly hired by the company.

In addition to premium calculation, foreign local subscribers differ from South Korean ones in the scope of household members recognized. The changes to the system mean that premiums are assessed according to individuals rather than households (those sharing a residence according to the resident registration table), with only the subscriber’s spouse and children under 19 years eligible for coverage. For South Korean subscriber households, parents, adult children, and siblings of local subscribers are also entitled to health insurance coverage. In the Kims’ case, both mother and daughter shoulder monthly health insurance premiums of 113,050 won, for a total of 226,100 won (US$186.21). MOHW has threatened to provide the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) with regular information on migrants aged 19 or older who have failed to pay 500,000 won (US$410) or more in premiums, warning that renewals of sojourn status will not be made available to those in arrears three or more times.

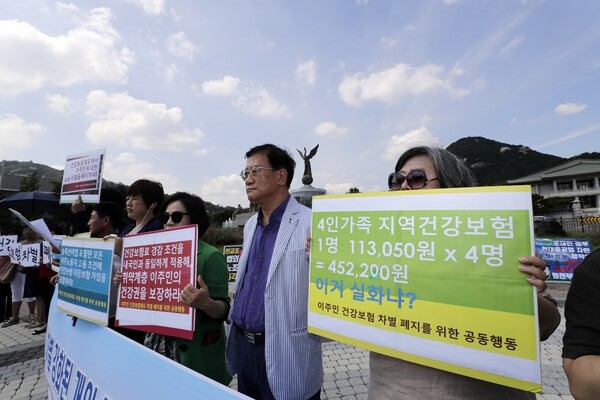

On Aug. 26, an organization called Collective Action to Abolish Health Insurance Discrimination against Migrants – made up of groups working to support Kareisky, Chinese Koreans, migrant workers, and refugees – held a press conference in front of the Blue House to demand that countermeasures be put in place.

“Since local health insurance enrollment was made mandatory for foreign residents, poor migrants have been receiving premium bills anywhere from three or four times higher to dozens of times higher than they were before,” the organization said. In particular, the large reduction in the scope of household members recognized for local subscribers means that elderly parents and children who live with them and are unable to work due to health issues have to also pay premiums.

According to the current law, migrants with approved sojourn status who work at least 60 hours a month should receive health insurance coverage through their workplace. Apart from those working under 60 hours a month (15 hours per week), anyone at a workplace with at least one employee is entitled to health insurance, regardless of nationality. But many overseas Koreans, recognized refugees, humanitarian sojourn residents, and other migrants work in poor environments where workplace enrollment is not guaranteed.

Even migrant workers in the agriculture and livestock industries – where the government sets entry permit numbers through the employment permit system – are unable to enroll through their workplaces; instead, they are automatically enrolled as local subscribers and have to pay at least 113,050 won per month. Due to factors such as long working hours and difficulties communicating in Korean, a large number of migrants do not receive hospital treatment even when they do suffer health issues.

MOHW explained that the system changes were improves intended to expand health insurance cover and provide rational management amid a rise in the number of foreign residents in South Korea. But the policies were devised in a slapdash fashion, with no attempts even to accurately investigate the conditions faced by migrants. In December 2018, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination recommended that the South Korean government examine improvements to allow all migrants to enroll in health insurance with the same premiums paid by South Korean citizens.

“In developing social insurance premium policies that don’t even involve budget outlays, how does it make sense to implement the system without a single survey to see what the levels of household income are for different sojourn classifications, what their housing conditions are, or whether they are actually receiving their pay when they are employed?” asked Cho Yeong-gwan, an attorney who serves as secretary-general for the group Miracle Friends.

“They need to discontinue this system at once and work on ways of supplementing its deficiencies,” Cho advised.

“They need to discontinue this system at once and work on ways of supplementing its deficiencies,” Cho advised.

By Park Hyun-jung, staff writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 3Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 4‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 5Up-and-coming Indonesian group StarBe spills what it learned during K-pop training in Seoul

- 6The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 7[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 8Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 9Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 10Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says